October 2018

STEPHANO HAARHOFF, Department of Agronomy, Stellenbosch University and DR HENDRIK SMITH, conservation agriculture facilitator, Grain SA

Food production is under constant pressure due to variable environmental factors and a growing population. Crop production practices should be adapted to meet the ever increasing food demands and to ensure economic and environmental sustainability.

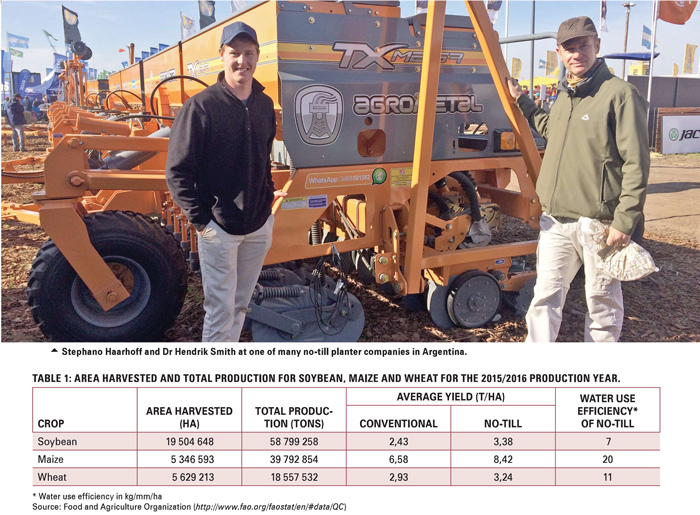

Argentina produces enough grain to sustain roughly 200 million people on an annual basis with a current human population of only 42 million people. This makes Argentina one of the global leaders in grain production. Main crops include soybean, maize and wheat (Table 1).

Climate and soils of Argentina

The Argentine Pampas is an extensive plain of approximately 760 000 km2 extending from the eastern Atlantic coast across central Argentina to the Andean foothills in the west. The natural vegetation consists predominantly of grasslands, although 54% of the area has been converted to cropland. Mean annual rainfall ranges from 200 mm in the west to 1 200 mm in the east at Buenos Aires.

Sandy soils are more frequent in the south and west, with loam and silty loam soils scattered across the interior. Silt loess soil is the predominant type found across the Argentine Pampas. It consists of wind-blown material (approximately 70% silt, 15% clay and 15% sand) with a very high crop production potential due to high water holding capacity and fertility. These soils are extremely sensitive to erosion by both wind and water if not protected.

History: Adoption of no-tillage

Conventional tillage played a big role in the Argentine cropping systems until the early 1990s, where the mouldboard and disc ploughs were central to the system. This led to extensive decreases in soil organic matter and nutrients, while high levels of soil erosion caused severe damage annually.

Grain yields varied according to the prevailing climatic conditions of each growing season, with good grain yields achieved with favourable rainfall and the reverse in low rainfall years. A few producers across Argentina realised the cropping system they followed was not sustainable, from both an economical and environmental point of view. They desperately had to search for alternative approaches.

At the end of the 1970s, the first long-term no-tillage field trials were initiated. The results were not positive as the technology that is needed for a fully functioning no-tillage system was absent. One of the major problems was the absence of effective weed control technology. As weed removal by soil tillage was not possible, weeds established continuously and resulted in crop losses.

At that stage, cropping systems consisted of a double-cropping system. Wheat was grown during the winter and soybean had to be established as soon as possible after the wheat had been harvested. This provided a quick second crop harvest and effective soil water use by crops.

The lack of weed control technology was highlighted by this system. If the period between two subsequent crops was too long, weeds established and used available soil water.

Producers started to discuss no-tillage amongst themselves and thought this new idea was foolish and that such a big revolution in the system was impossible to put into practice. Understandably, this new concept of no-tillage was difficult for producers to comprehend – especially for those who had been following conventional practices for many years.

The newly introduced technology and ideas were foreign and the conversion was huge. Most producers started to realise the potential of no-tillage when crop yields increased and the impact of the new methods on the environment was not significant when compared to the traditional, conventional methods.

By the end of the 1980s, the Argentine Association of Direct Sowing Producers (Aapresid) organisation emerged. This organisation is non-governmental, non-profit and patronised by producers and agronomists from across Argentina. The mission of Aapresid is to promote sustainable production systems of food, fibre and energy through innovation, science and network knowledge management. Currently, Aapresid is funded by approximately 2 000 producers from 30 regions across Argentina.

Input (chemical) companies saw the opportunity to increase their business and initiated help in adapting technology associated with no-tillage. This led to the release of glyphosate herbicides and opened the door to promote no-tillage much faster, as effective weed control was now a possibility.

The glyphosate herbicide was, however, very expensive at that stage, but due to the overall lower inputs of a no-tillage system it was possible for producers to follow this route. As time went on, glyphosate herbicides became cheaper, which further improved the economic viability of the system.

As both wheat and soybean were part of the cropping systems during the early stages of no-tillage adoption, producers realised the possibility of including other crops such as maize. As time went on, producers became more familiar with the new concepts and methods of no-tillage and viewed technology as a possible gateway to adapt the system according to their needs.

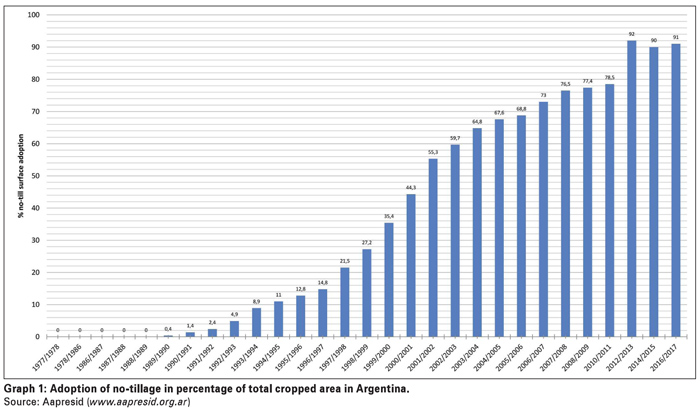

In 1996, Roundup Ready soybeans were introduced in Argentina. Soon after, a large number of producers entered the no-tillage system in a very short period of time (Graph 1). Glyphosate could now be used for weed control during the soybean growing season and fallow periods. Weeds that were difficult to control could now easily be dealt with.

From there onwards, the surface under no-tillage doubled annually. Soybean was the principle crop, while the area under wheat and maize was very low. However, monoculture soybean production was harmful for the ecology of the Pampas and led to, among others, depleted soils, primarily due to the low levels of crop residue production, soil organic carbon reduction and poor nutrient cycling.

After some time, producers introduced maize and wheat more frequently in their production systems to increase crop diversity. Currently, the introduction of cover crop species such as triticale, oats and radish are being investigated (by researchers and producers) to further increase crop diversity, livestock integration, more effective weed control between summer crops and improved soil water utilisation.

In 1992, only 1,8 million ha were under no-tillage in Argentina. This figure currently stands at 34 million ha, representing 91% of the total cropped area (see Graph 1).

Conversion process and key components

Producer’s associations initially began no-tillage research in Argentina. Producers conducted field trials on their farms to generate new information and to investigate the response of both crops and soil to the newly introduced system.

These producers shared all their knowledge and experiences with one another because it was the only clear and trustworthy type of information available. The philosophy of the association of no-tillage producers was to improve all together and overall across Argentina.

They were open to share all their information and obtain new information from different parts of the country. Furthermore, they adapted the information for each part of the country for all localised conditions and situations. In addition to on-farm field trials, no-tillage producers held field meetings to share and discuss new information, difficulties and possibilities to achieve their goal: To produce more efficiently and by means of a more sustainable approach.

To achieve this, teamwork was needed from all role-players within the crop production industry such as the producers, input companies and researchers. During the latter stages of the 1990s, technology companies supported the newly introduced no-tillage system and contributed towards the adoption of no-tillage in Argentina.

When the number of producers attending the meetings on no-tillage increased, several technology companies wanted to be included in the transformation of the system. Accordingly, the Argentine federal research and extension organisation National Agricultural Technology Institute (INTA) saw the possibility of the no-tillage system and initiated scientific research.

Since then, specific aspects with regards to no-tillage systems have been researched to address problems faced by producers continuously adapting and improving their no-tillage systems in various parts of the country. This helped to promote no-tillage so 80% of the total production land was converted within 15 years.

No-tillage in a system-based approach

In Argentina, there now is a big emphasis on the inclusion of several principles or practices during the application of no-tillage in a cropping system. This importance of a system-based approach has not only been acknowledged in Argentina, but globally as well. South Africa has been emphasising this systems concept for the past ten years or more.

In Argentina, there now is a big emphasis on the inclusion of several principles or practices during the application of no-tillage in a cropping system. This importance of a system-based approach has not only been acknowledged in Argentina, but globally as well. South Africa has been emphasising this systems concept for the past ten years or more.

The success of a no-tillage system does not solely depend on the mode of soil disturbance, but the total agro-ecological management and improved technology that comes with it. Proper crop residue management, crop rotation, integrated weed and pest management strategies, integrated soil fertility management and the integration of livestock should complement the system in association with modern technology, which transform no-tillage to a complete conservation agriculture (CA) system.

It has been realised that no-tillage is not enough to control soil degradation and regenerate soil and agro-ecosystems, which require the quality application of all the CA principles.

What no-tillage offers producers in the humid Pampas

The principles of the no-tillage or CA system remain the same regardless of the location. However, the success of the system depends on how these principles are applied and adapted in each producer’s conditions. Each set of social, economic, soil and climate conditions presents its own challenges and therefore requires different approaches.

The implementation of no-tillage in combination with adequate soil cover and crop rotation (or CA) has the following advantages for Argentine producers:

- Soil erosion control is improved.

- Improved soil water balance for crop growth.

- Improved soil physical structure with more stable macropores.

- Increased chemical fertility.

- Increased soil biological activity and organic matter content.

- Possibility to intensify the cropping system with crop diversity.

- A more productive and simplified cropping system.

It is important to recognise that a total mind shift, or rather a permanent open and learning mind is essential for all participating parties to continuously adapt their no-tillage practices to successful CA systems.

Mr Mario Bragachini, a legend in Argentina for his work on agricultural machinery and no-tillage, emphasised it perfectly: ‘Most producers talk about how much rain they will or did receive for crop growth. They should rather talk about how much water the soil can offer the crops. This includes surface run-off, evaporation and soil water holding capacity. The nature of this approach is such that emphasis is not placed on how much rain will be received, but rather how the soil can be managed to offer the crops the best chance possible with what is available at that point of time. That is when you manage the soil.’

Publication: October 2018

Section: On farm level