Can you remember the last person you had a fight with? Was it at work or at home? Can you remember what it was about? Have you managed to make peace with them? Are you still angry? Try as we may to eradicate it, conflict remains an inevitable part of our personal and working lives.

What is conflict?

Conflict may escalate quickly at times or it may be suppressed or simply forgotten. Conflict often spreads as we share our perspective, our side of the truth, with our families, friends, colleagues and even complete strangers. Conflict can even be carried from one generation to the next.

It is all around us. But this is not necessarily a negative thing. Conflict can be productive and can even bring about much needed adaptation or innovation. It all depends on how it is perceived and how it is dealt with. This is as true when it comes to businesses or organisations as it is when it concerns individuals. One can only deal with conflict, however, if it is recognised as such. It might surprise you to learn that sometimes people do not even realise that they are living or working in a state of conflict.

There are many forms of conflict in addition to what we might experience in terms of personal relationships. At a social level in South Africa there is conflict emanating from land reform, conflict between different cultures, races and genders. There are also forms of conflict peculiar to businesses or organisations.

Business or organisation conflict can be said to occur when co-workers or departments fail to make progress with a task because of disagreement over what they should be doing or their goals (task conflict). It can also occur when colleagues disagree over which policies or procedures to follow to accomplish the task at hand (process conflict).

Conflict exists at multiple levels in many different contexts and can be defined in many ways. However, it is always primarily a disagreement with another person or group and it largely arises when we feel that a person or group threatens or obstructs our interests.

Is conflict always bad?

Is conflict always bad?

As implied above, not all conflict is unhealthy or dysfunctional. In organisations constructive or functional conflict is sometimes necessary and even, at times, vital to performance and success.

Indeed, Bruce Tuckman (a famous educational psychologist) saw conflict as an essential part of the formation of groups capable of learning, working together and achieving goals. In his Stages of Group Development, he theorises that any group will only reach the final stage of performing if they have moved through a ‘storming’ stage. This is a stage where they openly engage in conflict that helps them to establish agreed-upon values and rules or norms for the group (the ‘norming’ stage). A similar view is shared by Daniel Coyle, the author of The Culture Code: The Secrets of Highly Successful Groups. In this best-selling book, Coyle states that the success of any group can be measured by two key moments. One of these is how the group responds to its first conflict.

From research and theory, it appears that the effective and productive performance of any group requires exploring, harnessing and resolving conflict. But it is a balancing act. Too little conflict in an organisation can result in employee complacency and sluggishness, while too much can lead to stress and burnout and negatively affect collaboration. Conflict within organisations can be thought of like an irrigation pipe: Too little pressure in the system and no water will come out; too much pressure and the pipe will most probably burst. Too far, in either direction, and productivity is put at risk. Just the right amount of conflict is needed in order to make the organisation function effectively.

Is there only one way to handle conflict?

It is important to acknowledge that conflict will be a part of your life. Better yet, it is important to acknowledge that constructive conflict should be part of your life. The question is: How can we work with conflict to ensure that both we and the people we manage are productive and collaborative?

Perhaps the most important parts of successful conflict management are to effectively manage emotions and to develop our emotional intelligence or EQ. EQ refers to the ability to identify and manage one’s own emotions and those of others. An important part of managing our emotions is to understand that different people handle conflict differently.

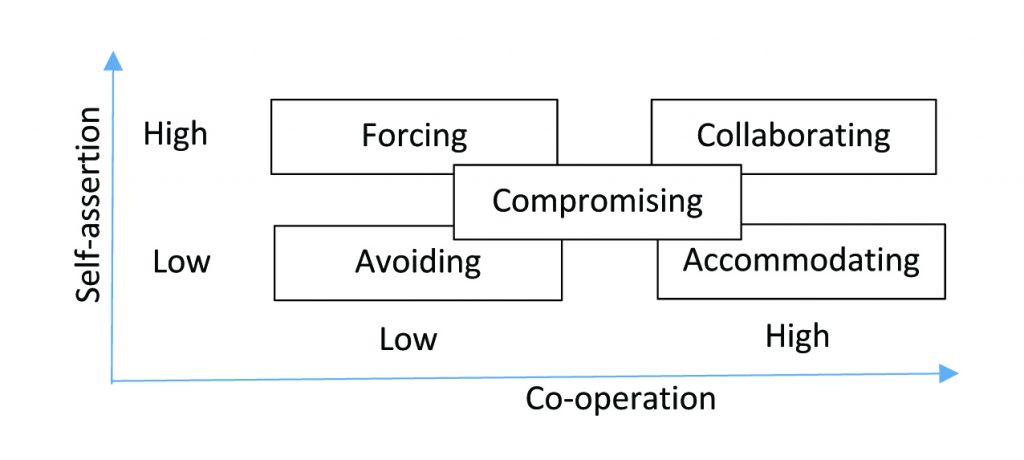

The different ways people handle conflict can be related to how much they are concerned with meeting their own needs or those of others. Those who are concerned mostly with their own needs (those who are self-assertive) will tend to be forceful in a conflict, while those who are more concerned with the needs of others (those who are cooperative) will tend to be accommodating. Those who find it difficult to assert themselves in a situation and who do not wish to co-operate, will simply avoid participation. Perhaps the most successful way to handle conflict is to show both confidence and a concern for others; this is when we collaborate and compromise.

However, even the same person will not use the same style in all situations. A lot can depend on the situation as well as those we find ourselves in conflict with. For example, if you are involved in a conflict that is not important to you (like your children fighting over who gets to choose the TV channel), you might choose the avoiding style and just ignore the problem or person. When negotiating your salary, you may choose the compromising style and when faced with a rude or even a drunk person, you might choose the forcing or avoiding style.

Aiming for a solution

While we all have different and context-dependent styles of handling conflict, when it comes to resolving it, we need to control our emotions. In the bestseller, Anatomy of Peace, the Arbinger Institute suggests that we should reject any impulse to focus exclusively on the conflict, as this may often escalate it. When we focus on conflict, we usually only see two alternatives, namely the two sides — yours and mine. Stephen Covey, in his well-known book the 8th Habit of Highly Effective People, refers to this as the ‘scarce mentality’. It would seem we are limited to these two options. Covey implies that we should shift our focus to finding a third alternative. This alternative should be to try to find a way so that there are no losers in the conflict: a win/win situation. A win/win approach (collaborating approach) is when both parties walk away from the conflict feeling as if they have won.

In my experience, effective conflict resolution means listening to the other party. Acknowledging the emotions of the other party may also help. But effective listening does not suggest listening to respond, but truly listening to understand. This means we are not constantly thinking of how we are going to reply to, counter or contradict what they are saying. Although difficult, it is also important to remain calm in a conflict situation. A shouting match will only result in a scarcity mindset, with a definite winner and a definite loser.

Steps in handing conflict

Listening will allow you to clarify what the disagreement is about. This is the first step to resolving conflict. Effective listening will also allow you to establish a common goal for both parties and to find ways to meet the common goal and explore the barriers that prevent the achievement of that common goal. Once this has been explored, you can agree on the roles and responsibilities of both parties. But listening remains the key ingredient. You may need to check your understanding of what the other person is saying and the other person’s understanding of what you are saying. This will avoid miscommunication owing to misinterpretation.

Conclusion

The skill of listening remains one of the most important aspects to effective conflict handling. Only through proper listening, will you deal effectively with conflict. Another key aspect is understanding yourself, knowing your trigger points and which behaviours or attitudes cause you to become angry or emotional. Sometimes the best approach to a non-important conflict is to walk away. But if the relationship or goal is important to you, then stay focused on listening. Also remember that unacknowledged conflict can never be resolved and that conflict, when productively worked through, can only strengthen groups and relationships.

To conclude, while we cannot resolve each and every conflict we are involved in, with understanding and self-awareness, we can prevent conflicts from becoming worse.

For further information or advice contact Dr Leon Bezuidenhoud on 051 401 3001 or send an email to bezuidenhoudl@ufs.ac.za.