March 2015

JAN GREYLING, Department of Agricultural Economics, Stellenbosch University

If asked to estimate the share of the agricultural sector in the economy, most people respond that it is above 10%. This is a reasonable estimate given the fact that the sector uses more than 80% of available land and around 60% of available water. In reality the sector represented less than 10% of the economy in 1960 and currently this figure is below 2,5%.

South Africa is no exception, since the US agricultural sector currently represents around 1% of GDP. There they have more lawyers than producers and more drycleaners than farming operations! One just has to ask if we are heading towards a world without agriculture? Does the sector still make a contribution to the economy?

Luckily this has been the topic of numerous studies since the mid-1950s. One of the most popular ways to analyse the sector’s contribution is to evaluate it according to five main themes: The role of the sector as provider of food, earner of foreign exchange, employment source or provider, source of capital and buyer of goods or provider of inputs to the manufacturing sector, the so called market linkages.

This article will elaborate on the contributions of food, trade, linkages and employment of the sector to the greater economy.

The food supply

The role of the sector as food provider is particularly relevant at the moment given the rise to prominence of concerns over food security. In general, food security is defined as having reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food. Note that this does not imply food self-sufficiency as often implied in political debates.

According to Statistics South Africa the typical South African household spends more than 70% of its food budget on four main food groups: Meat (25%), bread and cereals (26%), milk, cheese and eggs (9%), and vegetables (10%).

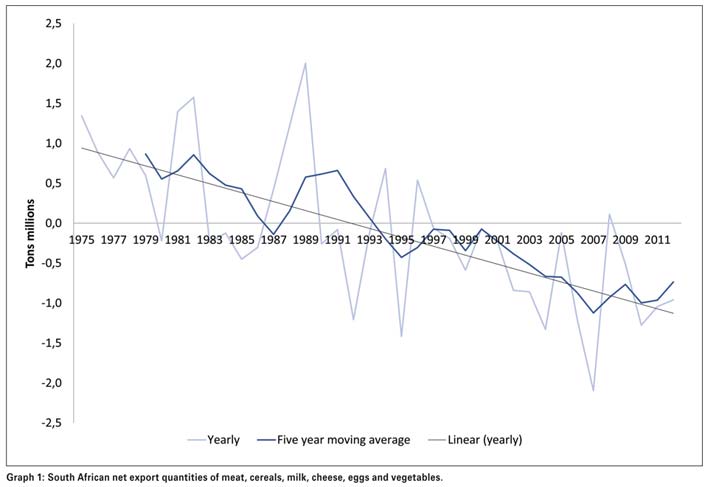

An analysis of the combined net trade by quantity, in other words the combined net export tons less the net import tons of the main items in each of the four groups, provides a good indication of the country’s food self-sufficiency status.

The combined result of more than 30 food items is presented in Graph 1. It shows the actual values, the five year moving average to smooth out climatic variations, and the trend line. It is clear that the trend is downward over time and that South Africa is currently not self-sufficient in terms of the main food items consumed since the mid-1990s.

From a self-sufficiency and import substitution perspective one can argue that this is a terrible situation and that it would lead to rising food prices. The reality, however, is that inflation is currently much lower than in the 1980s.

Agricultural trade

One would think that the increase in primary food imports would have a negative impact on the agricultural trade balance, but the opposite is true since the country is still a net exporter of agricultural products by value. The sector therefore does not contribute to the negative trade balance.

The deterioration of the country’s food self-sufficiency status and maintenance of a positive trade balance can be explained through structural shifts in the allocation of hectares under grain production, composition of agricultural trade and changes in food consumption patterns. This is the result of the deregulation of agricultural marketing and liberalisation of agricultural trade that was completed by the late 1990s.

This resulted in lower grain prices that prompted producers to remove marginal land from crop production, thereby decreasing the area planted under maize and wheat by more than a million hectares respectively.

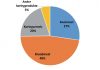

The country currently imports almost 50% of wheat consumed. On the positive side, this process gave fruit and grape producers access to the international marketplace where they compete quite successfully. During the 1990s and 2000s, exports in these items grew at an average of 6,5% per year, thereby increasing their share in total agricultural exports from 29% to 68%.

Another major shift is changing meat consumption patterns in response to price. Per capita beef consumption declined from its highest level of 24 kg per person per year during the 1980s to the current level of around 16 kg per person per year. The consumption of poultry on the other hand grew from 6 kg per person per year to the current level of 36 kg per person per year, of which 25% was imported in 2012/2013.

Collectively these trends underscore the importance of continued investment in transport infrastructure in order to ensure that food items can be produced and moved cost-effectively. This is particularly important from a food security perspective since these items represent a large portion of the budget of a low income household. Such investments are also important for ensuring and expanding the competitiveness of our high value food exports.

Linkages

The fact that the sector represents less than 2,5% of the economy does not provide the true picture of the sector’s impact on the greater economy since the sector does not operate in a vacuum – it buys inputs from the manufacturing sector, provides raw materials for manufacturing and purchases a host of services. How big is the impact of the sector then?

One of the ways of looking at it is to sum the GDP share of primary agriculture and all closely related sectors, i.e. agribusinesses. Examples of agribusinesses would include farming operations, input manufacturers, input suppliers and co-ops, food processors, distributors and traders, and others. Our research shows that the agricultural and related sectors represented around 7% of GDP in 2010.

This approach, though correct, is limited because it simply looks at the direct contribution of the sector to GDP. An interesting alternative is the use of multipliers to estimate the indirect impact of changes in the sector on the rest of the economy. These multipliers, calculated from national statistics, show that primary agriculture has a backward linkage of 2,14 (the fifth highest in a 20 sector grouping of the economy).

This means that a R1 million increase in demand for agricultural output will increase the combined output of the other production sectors in the economy by R2,14 million (inclusive of the original R1 million of the agricultural sector output). The closely related food, beverage and tobacco industry is calculated at 2,3 – giving it the third position.

The calculated forward linkage of the sector is 1,81 (the 18th highest of a 20 sector grouping of the economy). If there is a R1 million increase in the cost of value added in the agricultural sector, then the combined value of output of the other sectors in the economy will increase by R1,81 million as a result of price increases.

Employment

Statistics on agricultural employment differ according to definition and source, but it is safe to say that the sector employs around 700 000 workers. This makes the sector one of the biggest employers in the economy. It is also important to note that the sector is labour-intensive compared to other sectors, because it employs about 4,6% of the total labour force. The mining and manufacturing sectors, in comparison, represent 8,5% and 12,5% of the economy whilst employing only 2,3% and 11,8% of the labour force respectively. The agricultural sector therefore uses two units of labour per unit of value added, whilst the ratio is 0,3 and 0,94 for the mining and manufacturing sectors.

Investments in the sector, such as the expansion of irrigation capacity for example, could deliver high employment creation returns. On the negative side this is indicative of low labour productivity in the sector.

Conclusion

The South African agricultural sector continues to play an important role in the economy regardless of its declining share in GDP. Contrary to popular belief, the country is not self-sufficient in its food supply, but does not operate as a net importer of agricultural products due to the exports of high value items such as fruit and wine.

The sector also ranks high in terms of its backward linkages with the manufacturing sector, and acts as a major labour-intensive employer in the economy. Continued investment in extension, research and infrastructure (particularly transport and irrigation) will have a significant impact on a large number of households and the greater economy due to its employment and food security effects. This would also ensure that the sector maintains its international competitiveness and resulting positive trade balance.

Publication: March 2015

Section: Relevant