April 2018

JENNY MATHEWS, SA Graan/Grain contributor

The term ‘climate resilience’ refers to ‘the ability or capacity of a community to bounce back or weather the storm through resisting, absorbing or accommodating the shock of an extreme climate event and then recovering and reorganising afterwards’.

In 2007 Prof Guy Midgley already wrote, as a co-lead author of an IPCC report, that ‘The resilience of many ecosystems is likely to be exceeded this century by an unprecedented combination of climate change, associated disturbances (e.g. flooding, drought, wildfires, insects, ocean acidification) and other global change drivers (e.g. land use change, pollution and overexploitation of resources)’.

In 2018, there is growing evidence that this projection has been borne out by observations in several ecosystems – for example, the coral reefs of the tropics have seen ecological collapse over vast areas, the increasing mortality of forest trees has been observed around the world, and the frequency of severe wildfires has been increasing in many ecosystems. How can we increase the resilience of natural and managed ecosystems to help us cope?

Find the silver lining

Find the silver lining

Surprisingly, even now it’s not uncommon to hear people scoff about the ‘theory of climate change’ saying they believe ‘it’s just another weather cycle’ and not permanent change – and such talk is just scaremongering. Prof Midgley doesn’t even go there – in his eyes, and in the data produced by thousands of scientists and ‘citizen scientists’ worldwide, the theory is incontrovertible. Debating the issue is now wasting valuable time to address the impacts.

After a lifetime of work in this arena, climate change ‘is no longer a myth’. He says it is a serious threat – ‘a game changer’. In spite of this, a message of hope underpinned his address to Congress. In that headspace it becomes possible to find ‘the silver lining’, which is where opportunity lies.

Reality check

At the World Economic Forum in Davos where world business leaders examine the medium to long term threats to world business, the latest assessment of events, with the highest impact on business – and the highest likelihood of occurring, are considered to be extreme weather events and natural disasters.

It places the spotlight on ‘hotspots’: Water crises, failure at climate change mitigation and adaptation and food crises. Whether climate change is real or not…is no longer a debate amongst the business leaders of the world. This has become an issue of profits, economic activity, human well-being and risk management.

The solution space

How has the climate been changing?

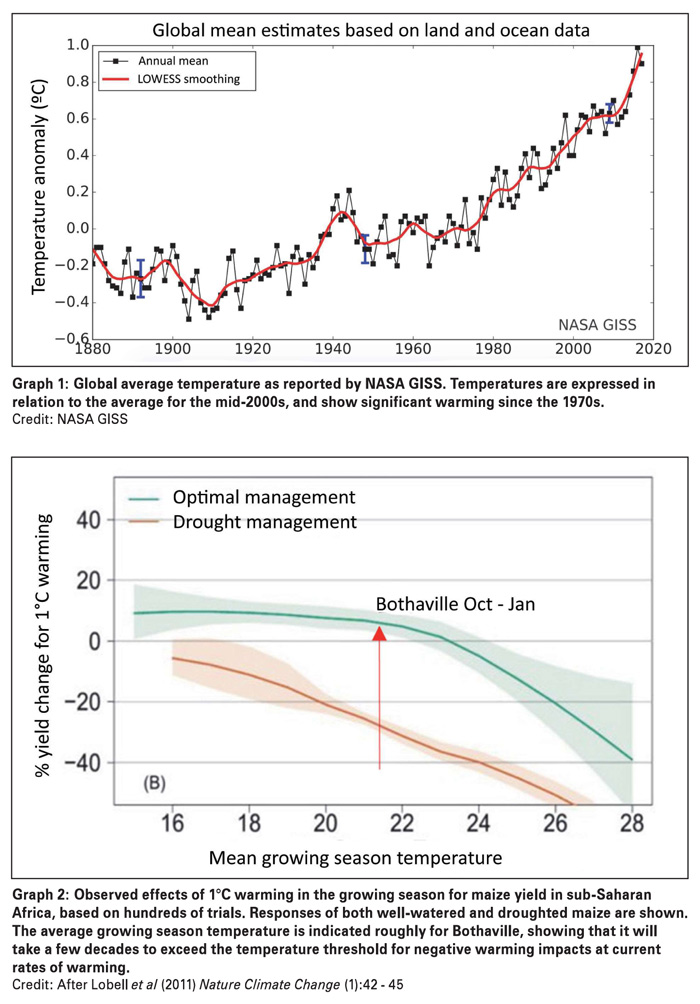

Prof Midgley says that scientific data tell a clear story of increased global temperatures driven by rising concentrations of greenhouse gases (GHG’s) in the air around us: Carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide.

These are radiatively active and once released into the atmosphere cause warming. Prof Midgley noted that we need CO2 – without any CO2 the global average temperature would be -15°C and the planet would be frozen. Unfortunately, additional GHG’s are now being added and these can be largely attributed to anthropogenic (human) activities in the industrial era.

Since the late 1900s emissions have accelerated with population growth, agricultural expansion, dependence on fossil fuels, deforestation and land use changes. The new Sustainable Development Goals are a major international attempt to achieve a transition from these trends to a sustainable and developing environment. It is within these scenarios that our potential solutions lie.

What is likely to happen?

What is likely to happen?

We have choices to make with regard to how much carbon we emit and how much we warm the world. ‘The future of our planet is in our hands – including how efficiently you can remain in farming.’ Prof Midgley acknowledged the potential futures are diverse and depend strongly on national and international policies. Under business as usual global development, we are set to warm the planet by 5°C or more by the end of this century. Under scenarios that rapidly roll out renewable energy solutions and increase the capacity of the earth to absorb CO2 back into ecosystems, we might avoid 2°C of warming. Political will and global to local action will make the difference.

When might these things happen?

At present we are on a high emissions trajectory to warm the world by between 3,2°C to 5,4°C which means 6°C to 10°C across sub-Saharan Africa towards the end of the century, i.e. desert conditions. We have to get onto the low emissions pathway as far as possible. The longer we delay, the harder it becomes to achieve this.

Even under the best-case scenario, technology which draws carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere is needed and this is one important place where there is opportunity for agriculture. Carbon can be naturally sequestered (stored) in soils and vegetation, but at present much escapes into the atmosphere due to inefficient management approaches. We must find ways to lock in more carbon and reduce emissions into the atmosphere.

Prof Midgley pointed out that although the warming pattern in South Africa has been positive over the last 50 years at 1°C to 1,5°C warming, we have a regional advantage because our climate is semi-continental. Being buffered by the oceans protects us against the worst effects of global warming for some decades. This offers us yet another opportunity, as the rest of the world continues to warm over the next few decades, and in the continental climates of the northern hemisphere damaging extreme events increase in frequency.

What does this mean for grain production?

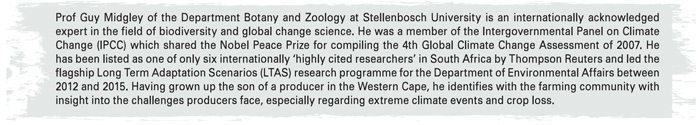

Researchers have found a 1°C temperature increase boosts maize production in well-watered situations for sub-Saharan Africa

– but only up until a 23°C growing season temperature average. Above 24°C production levels drop significantly (see Graph 2). If maize is droughted, warming causes adverse effects from as low as 16°C.

This information is useful to assess how much time we have to adapt to what might happen over the next ten to 20 years, and suggests that if rainfall does not decrease, the major maize growing regions have one or two decades available to adapt to ongoing warming. It will therefore be important to build resilience in the short term to climate variability especially by improving our ability to predict adverse climate events like El Niño conditions, and retain moisture in the soil to reduce vulnerability to short term dry spells.

Continuing with his ‘silver lining’ message, Prof Midgley noted South Africa is better off than some competitors, e.g. the US climate is ‘going crazy’. The melting of the Arctic ice sheet is disturbing circulation patterns around the North Pole, resulting in extreme warming/cooling events which are already affecting peoples’ lives. Prof Midgley also said producers need to stay alert, because new problems arise as temperatures warm, e.g. fall army worm. Early warning systems must be put in place and producers must be equipped to manage such invasions.

What can be done about it?

Reduce GHG emissions

Capture emissions in the soil. The land we manage has a role to play in carbon storage. The ability to sequester carbon could be of high value in the future.

Soil management

Halting soil degradation will gain soil carbon and have a wide array of other benefits. Conservation agriculture has a role to play. Prof Midgley suggested there may be a conflict between continuous pursuit of higher yields and a conservation agriculture approach which may sacrifice yields but score dramatically in terms of building resilience and carbon sequestration.

Take home messages

- Climate change is real.

- South African grain producers have time. Food security issues north of borders which will result from climate change impact, will present opportunities for South African producers.

- The four building blocks of resilience are:

- Soil management

- Pest management/monitoring

- Cultivar selection/testing; new technology

- Climate monitoring and prediction.

Producers need to:

- Get informed about climate variability and build resilience.

- Call for better technology and predictability over a ten-year period.

If government doesn’t help, it will be up to us.

Further references

https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/presentations/briefing-bonn-2007-05/sectoral-impact-ecosystems.pdf

https://www.sanbi.org/biodiversity-science/state-biodiversity/climate-change-and-bioadaptation-division/ltas

Publication: April 2018

Section: Review on Congress