April 2018

JENNY MATHEWS, SA Graan/Grain contributor

Prof Fred Below is Professor of Plant Physiology in the Department Crop Sciences at the University of Illinois. Illinois is right in the centre of the lush maize belt and it is here that Prof Below specialises in examining factors which limit crop productivity, particularly in maize and soybeans.

He has developed a teaching approach which he calls ‘intelligence intensification’, which highlights the most important factors that contribute to increased yield.

The world record maize yield was achieved this past season in the USA at 34,1 t/ha. The average yield record was also achieved this past season at 11,1 t/ha. The yield gap is the difference between what the average grower gets and what the record yield is. This is what Prof Below calls ‘the opportunity to increase maize yield with better crop management’.

A review of yield contest winners has shown that all 18 winners exceeded 20 t/ha in 2017, while five growers exceeded 25 t/ha and three others, 30 t/ha. Prof Below says it all starts with two key factors, namely better plant nutrition and making sure the plant is never stressed. Other crucial prerequisites for yield improvement, but not part of the seven yield wonders, are:

- Drainage.

- Pest and weed control.

- Proper soil pH and adequate levels of P and K, based on soil tests.

The seven wonders of the maize yield world

The seven wonders of the maize yield world

The weather

The elements always dictate when you can or can’t plant your crop and weather also dictates the success after planting.

Nitrogen

We can control N but we don’t have complete control over it. Every single thing about N is influenced by the weather. There are many examples of weather-induced N loss. In the USA there are even climate programmes which predict the availability of N. Too much rain and you will lose N. N moves downwards in the soil, which explains the N deficiency after heavy rain.

He then asked if N moves downwards and not sideways and where the best place to put the N would be. Their trials have shown that placing the N along the row has been worth about 0,6 ton yield advantage.

Hybrid/variety selection

All hybrids are not equal. In a trial between 44 commercial hybrids grown at three different sites in Illinois, there was a 3,8 ton range in yield at the Harrisburg site; a 5,9 ton difference between yields at Champaign and at Yorkville there was a range of 7,6 tons between the highest and lowest performing hybrids.

Prof Below says he is often asked which is the best hybrid:

- The best hybrid is the fullest maturity for the region build.

- The best hybrid is most often the newest and most expensive one.

He says producers can’t afford to use the same hybrid four years in a row and miss out on the benefits of improved genetics.

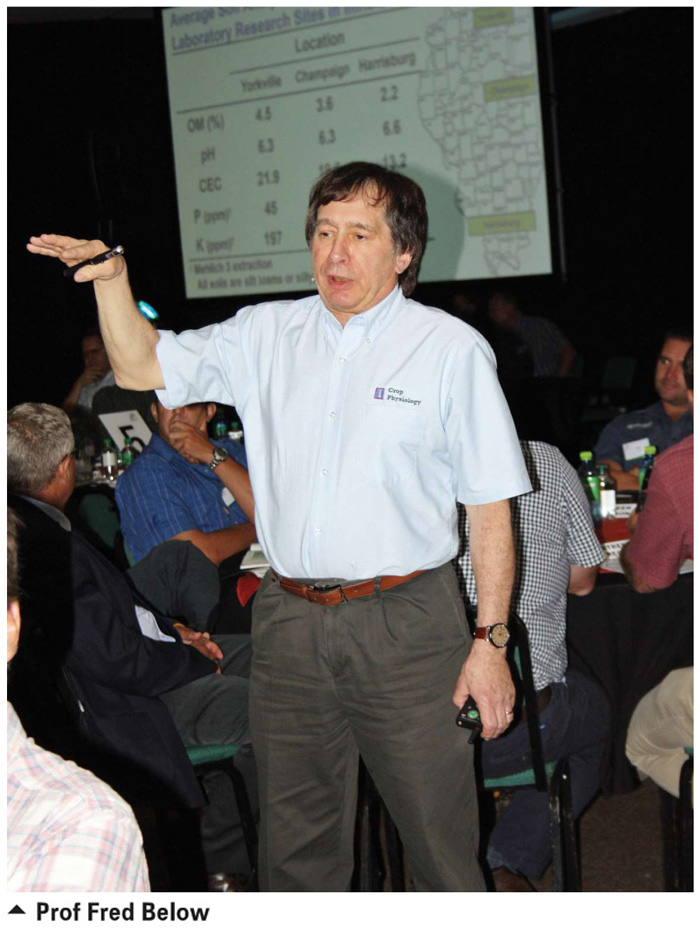

Previous crop

The previous crop grown in a field significantly impacts the new crop. In this region crop rotation is predominantly between soybeans and maize. Trials have proved that if soybean was the previous crop, it will boost the next maize crop by +1,6 ton; whereas if the previous crop was maize, it would negatively impact yield by -1,6 tons.

He calls it ‘the continuous maize yield penalty’ saying ‘it always gets worse with time’. Prof Below credits this to crop residue build-up over time (Photo 1). Residue acts like a sponge to prevent rain from infiltrating. It ties up nutrients and also releases chemicals, which interfere with the growth of the crop.

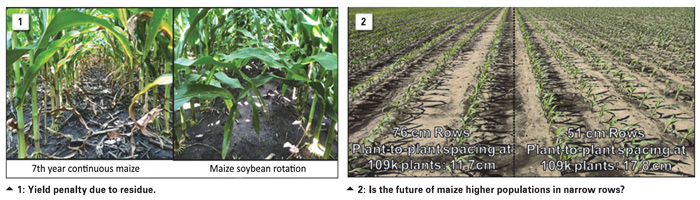

Plant density

Prof Below believes that producers don’t plant enough seed. He says this has to change in order to obtain higher yields (Photo 2). He believes this may be the South African producers’ problem, whilst acknowledging the high cost of seed and the risks we face with poor weather conditions.

Nonetheless he insists this factor has changed the most in the USA over the last 55 years. The USA yield increases by 1 ton every eight years. In 1965 the average yield was 4 t/ha (45 000 plants/ha in 91 cm rows). Today the norm is 79 000 plants per ha in 76 cm rows…‘and guess what, it’s only going to go up. It has to go up.’

Essentially grain yield is a product function of yield components: Yield = plants/ha (planting and emergence) x kernels/plant (flowering) x weight/kernel (grain filling). The function a producer has the most control over is plants/ha. In the USA plant density increases at a rate of 900 plants/ha/year despite high seed costs.

There is another factor to consider, i.e. maximum plant density. Beyond 94 000 plants/ha in 76 cm rows plant competition decreases yield. Prof Below says this will be reached within 15 years in the USA then rows will have to become narrower, e.g. 51 cm. The future of maize in South Africa has to be 76 cm rows. Narrower rows hold two advantages: They can better manage the higher density of plants and they intercept more early light.

A further benefit of narrow rows is higher moisture retention because the leaves shade the ground and prevent evaporation.

Tillage or no tillage

This is designed to control one of the preceding ‘wonders’ and can influence yields by up to 0,9 t/ha.

Growth regulators

‘This is the next big thing in agriculture.’ This is all about leaf health and leaf performance. Leaf greening is promoted through the application of strobilurin fungicides which are applied even in the absence of leaf disease. The greener leaves can give up to 0,6 t/ha increase in yield. There are risks which could decrease yields if the wrong growth regulators are used in wrong conditions, i.e. be very careful.

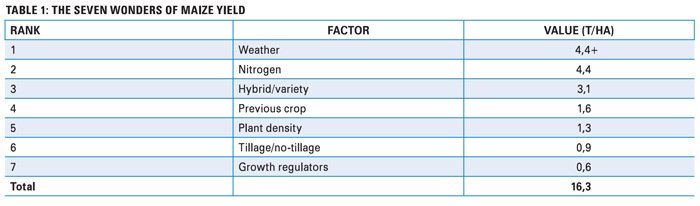

Table 1 sums up the seven wonders and their influence on yield potential.

No maize plant left behind

Higher maize yields are achieved where a producer optimises each of the seven wonders and their positive interactions and provides better prerequisites, season long weed control (modern hybrids don’t interact well with weeds) and balanced fertility.

Prof Below emphasised that in future both application and fertiliser technologies will be used to supply the required crop nutrition. Nutrients have a high harvest index value and producers must feed the plant, not the soil.

He summarised with his four most important nutrients for high grain yield namely, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulphur and zinc.

He advocates for fertilisation to be applied in bands – ‘where the roots will be’ – as this results in an incredible improvement in the early growth of the crop. A plant missing out on fertiliser is a plant left behind and that plant will never catch up.

Understanding the factors that have the biggest impact on yield gives growers the opportunity to increase yield.

Publication: April 2018

Section: Review on Congress