May 2017

DR ASTRID JANKIELSOHN, ARC-Small Grain, Bethlehem

Changes in the climatic environment have a significant impact on agricultural production as well as the suitability of an area for the production of a specific crop. Climate change has a direct, but also an indirect impact on crop yield by affecting the prevalence and distribution of pest insects, diseases and weeds.

Other factors such as increasing production costs and decreasing prices for crops influence the type of crop and the area planted to a specific crop. Not only are there constant changes in the natural environment, but the agricultural landscape is also changing all the time. During the past couple of years, the agricultural landscape in South Africa, especially in the Free State, has changed dramatically.

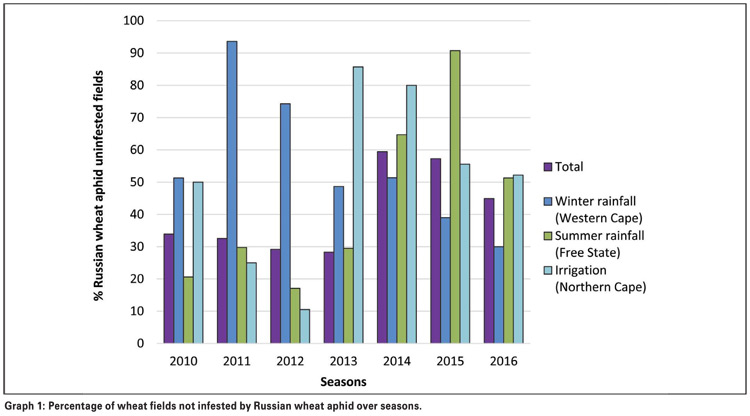

The area utilised for wheat production in South Africa showed a declining trend, decreasing by almost 43% from the 2004/2005 season and by 6% compared to the 2013/2014 season (SAGL, 2015).

The decrease in wheat cultivation is mainly a result of dryland wheat producers in the summer rainfall area (Free State), shifting from wheat to summer crops like maize and soybeans. There are numerous factors influencing this shift, from poor growing conditions and late rains to increased production costs and low wheat prices. This has resulted in the fragmentation of wheat ecosystems.

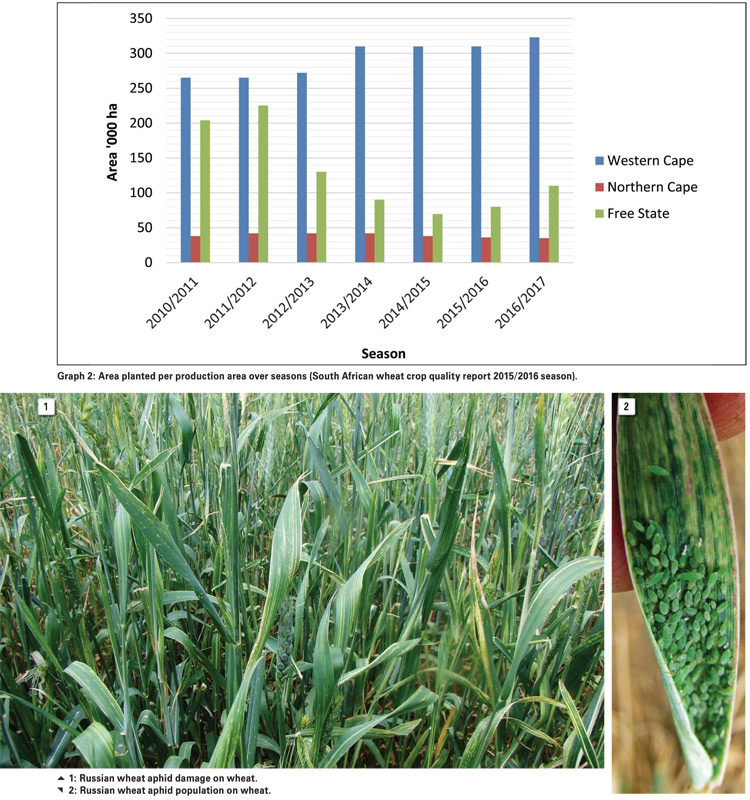

Russian wheat aphid, Diuraphis noxia, is a global wheat pest, which utilises wheat as its main host, with a limited number of alternative hosts. To date, four Russian wheat aphid biotypes (RWASA1 – RWASA4) are recognised in South Africa and these were monitored throughout the wheat production areas of South Africa from 2010 to 2016.

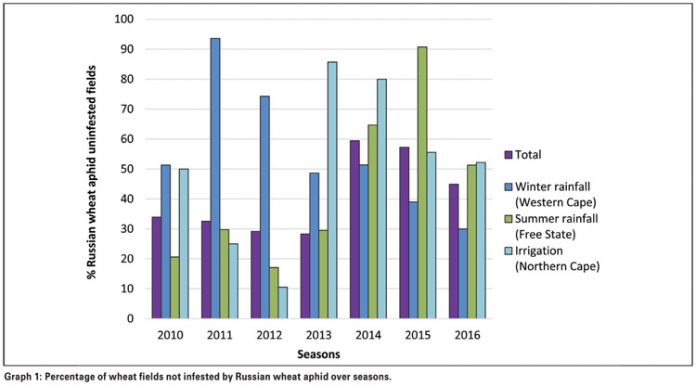

There has been a steady decline in Russian wheat aphid infestation of wheat in the summer rainfall region (Free State) during this period, as shown by the increased percentage fields monitored that had no Russian wheat aphid infestation (Graph 1). The decline of Russian wheat aphid in these areas can be attributed to the decline of RWASA1, RWASA2 and RWASA3.

There was a steady increase in RWASA4 over the seasons in these areas. This biotype, however, is limited to a few areas in the Eastern Free State. In the winter rainfall region (Western Cape), however, the percentage of fields with no Russian wheat aphid infestation decreased from 2010 to 2016, indicating an increase in Russian wheat aphid infestation in these areas (Graph 1), notably by RWASA1.

In the irrigation areas (Northern Cape) the percentage of fields surveyed with no Russian wheat aphid infestation increased drastically during 2013 and then decreased gradually from 2014 to 2016 (Graph 1), implying an increased aphid prevalence during recent times. The main biotype identified in these areas was RWASA1.

There was a decrease in the area planted with wheat in the summer rainfall area (Free State) over seasons, with a drastic decrease in the 2013 season, onwards (Graph 2). This coincided with a drastic increase in the percentage of fields not infested by Russian wheat aphid in these areas during the next season in 2014 (Graph 1).

There was a slight increase in the area planted with wheat in the winter rainfall region during the 2014 season (Graph 2). This coincided with a gradual decrease in fields not infested by Russian wheat aphid from 2014 to 2016, indicating an increase in Russian wheat aphid populations in the Western Cape (Graph 1).

The arrangement of habitat patches in landscapes plays an important role in determining the abundance and diversity of insects. Insects will increase within an area that contain the most suitable host plant and decrease with isolation of the patch. Wheat and barley are the main host plants for Russian wheat aphid in South Africa, but can survive on a few alternative host plants, including oats, wild oats, false barley and rescue grass.

This aphid cannot survive on any of the other crop plants commonly cultivated in South Africa. With a decrease in wheat cultivation in the summer rainfall areas of South Africa, the habitat for Russian wheat aphid became fragmented. Not only is there a spatial fragmentation, but also a temporal fragmentation when other crops are planted in different seasons.

This resulted in Russian wheat aphid populations being limited to certain habitat patches. At the same time, the beneficial insect/ pathogen complex associated with a wider crop spectrum increases, thereby exerting additional pressure on the survival of the pest species.

These observations emphasise the value of intercropping and crop rotation in managing insect pests and can serve as model for Russian wheat aphid management in areas where wheat and barley are still the predominant crops.

Publication: May 2017

Section: On farm level