Department of Agricultural Economics,

Extension and Rural

Development, Faculty

of Natural Science,

University of Pretoria

Grain storage has been a politically sensitive issue since the beginning of the 20th century. In the early 1900s hardly any grain storage was available in South Africa and the few facilities that existed belonged to milling companies such as Premier Milling in Newtown, Johannesburg. They erected some of the first, limited facilities to store flour, imported wheat and grain purchased from local producers.

SA Railways and Harbours only completed the building of the well-known Cape Town port grain elevator (30 000 tons) in 1924 – now converted into ‘The Silo Hotel’ – followed shortly thereafter by the Durban port elevator (42 000 tons).

This formed part of a government initiative to build 32 elevators almost simultaneously, to convert grain handling in South Africa from bags to bulk handling (SAR&H, 1923). It was only in the years that followed the promulgation of the South African Marketing Act in 1937 that storage was collectively built by producer co-operatives who, as agents, stored grain on behalf of the agricultural control boards that were established under the same act.

Competitive business

Significant progress was made in terms of grain storage techniques from the 1950s to the 1990s, with South Africa at times taking a global lead in some of the techniques used and achievements reached. However, with the demise of the marketing boards in the 1990s, grain storage was overnight transferred back into the hands of the private sector – with no more government grain storage contracts via control or marketing boards.

Every pit stored had to be paid for by either the producer, trader or miller/processor. Grain storage became a competitive business with the ex-co-operatives, now agri-businesses, competing to offer the best grain handling and storage services to prospective clients. Producers, who were previously members of the respective co-operatives, became shareholders and had to pay not only for storage, but also for all related services such as grading, weighing, screenings and drying. Producers therefore became clients and agri-businesses had to compete for their business.

In the initial years after deregulation, agri-businesses dominated the grain storage industry. Very few producers or processors had any significant storage capacity. Prior to deregulation, there was no need to build their own storage facilities as most producers were fairly close (less than 20 km) to professionally managed co-operative storage facilities, while processors could order grain as required, meaning on a weekly basis.

The on-site facilities at processors catered for off-loading, blending and probably not much more than a week’s worth of supplies. Traders did not exist. Any profits from grain storage and services were for the benefit of co-operative members.

In 2016 the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF) reported that when the maize industry was deregulated, 90% of the co-operatives converted to private companies. These private companies own 85% of the total maize storage capacity in the country, which is currently 16,3 million tons. There are 432 silos, of which 172 are on-farm (mostly small – a few 100 tons only) and 260 are commercial.

The commercial silos, owned by 17 silo owners, account for 94% of the available silo capacity country-wide. In South Africa there are three major commercial silo owners, namely Afgri, NWK and Senwes, who own 73% of the available storage capacity within the national grain storage market. Other important players are VKB and Suidwes.

Location

Capacity is by no means the only factor that determines the ability or effectiveness of the grain storage industry. Probably the second most important factor is location of an individual facility, or the even distribution of a number of storage facilities across the countryside to suit the needs of customers.

Some facilities’ turn-over in volume per year is two to three times their capacity, while others are not even filled throughout the year, i.e. less than once. Other important services include screening capabilities, the number of smaller silo bins for different grades, blending, aeration, fumigation, drying and in- and out-load capabilities, which all are important services in a modern competitive storage environment.

As more producers divested themselves of the shares they obtained from the co-operative transition to companies, client relationships with the former co-operatives were more than ever based on business and no longer on membership profit sharing. General goodwill, however, still plays an important factor in many cases.

Furthermore, in a free market environment and a national economy that is growing at only around 1% per annum, competition in the grain value chain is ever increasing.

Demand for on-farm storage

Farming activities increased in size, direct sales to processors became possible, and transport from the farm (on-farm loading) to processors has become a common practice. Therefore, the demand for on-farm storage and increased storage at processing facilities (mills) is on the rise.

By comparison to traditional storage, it is safe to say that the majority of growth in storage capacity is in on-farm storage and on-site storage at processing facilities. New facilities include a variety of modern techniques, including steel silos, bunkers, dams and silo bags.

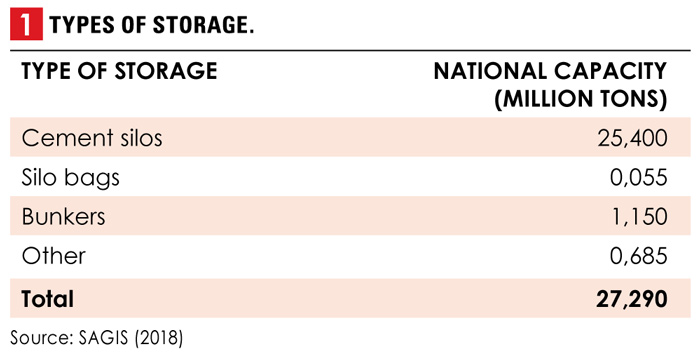

According to SAGIS (2018) the storage composition is as depicted in Table 1. These are inclusive of on-farm and processing facilities. The total capacity is estimated at 27,29 m3 of which 21,78 m3 is suitable for summer grains only.

A changing storage environment

Not too many years ago ‘grain was grain’, perhaps with a few different grades that were kept separate. Today the high-end of the processing and consumer market has all sorts of different requirements, ranging from different varieties catering for GMO-free products, grain and seed free of certain chemicals (used on farms) as well as traceability.

To compound the challenges, new technologies more easily allow for accurate testing of products supplied. The outcome of this on storage trends is still difficult to predict. On the one hand, only the sophisticated commercial storage operator can provide and guarantee these services.

However, if a large farming operation decides to focus on a niche market, such as GMO-free white maize on-farm storage, this may offer a viable opportunity for the operation to add value.

New technology also benefits smaller scale operations. Examples are:

- Grain temperature monitoring devices and moisture meters inside the silo have improved and are more cost effective.

- Weather stations on the outside can compare moisture and temperature inside the silo with that on the outside.

- Security cameras coupled with devices that indicate when electric motors are started have greatly improved the risk management capabilities of smaller facilities without necessarily appointing a large security force. Warnings are sent by an SMS and/or a control room could remotely log in.

- Sensors installed inside silo bins constantly monitor grain volumes, thereby improving security.

- Online system capabilities in managing producer profiles, deliveries, out-loading and stocks are more accessible.

- Equipment and testing in the intake laboratory are more cost efficient.

JSE/Safex

This is one area in which the agri-businesses still have a distinct advantage. It is difficult to obtain a JSE/Safex registration for a silo – not so much because of the facilities, but because of the guarantees that the owner needs to provide.

On the subject of guarantees or insurance, obtaining financing for on-farm grain storage (i.e. the product not the infrastructure), is extremely difficult. The irony is that some producers can afford to build the facilities, but they cannot afford to store the product – they need the cash for the next season. The moment there is an insurance company willing to cover grain on-farm storage risk, banks will be more willing to finance the grain which will bring more demand for on-farm storage facilities.

On-farm loading

Initially on-farm loading by transporters only occurred during harvest time and only a few mills were willing to risk taking grain directly from the farm. However, cost savings and the competitive nature of the grain industry has forced most mills to adopt this practice.

As producers started to erect their own storage facilities, this practice was extended to beyond harvesting time. On-farm loading and storage complemented each other perfectly and became such a threat to traditional storage practices that some agri-businesses started to offer services whereby they were willing to load grain on-farm free of charge and transport the producer’s grain to their traditional grain storage facilities, particularly those that are underutilised.

In the rest of this article some cost comparisons are looked at.

Steel silos

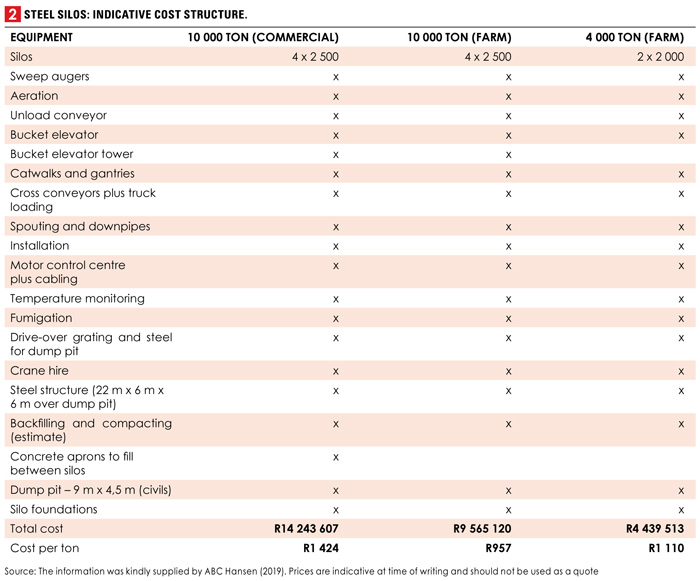

Table 2 gives the indicative cost structure for steel silos. Add approximately R500 000 for a weighbridge (22 m, 60 ton), including civils, excluding the roof. Add approximately R380 000 for a cleaner with a bucket elevator, 60 ton/hour.

Notes

4 000-ton farm system: This system has a handling capacity of 50 tons per hour, using downpipes, augers and bucket elevators. It is not suitable for high frequency usage, and is designed to be loaded and unloaded around one to two times per year. Unlined ducting is used, together with lower lifespan augers instead of chain conveyors for the handling.

10 000-ton farm system: This is an upgraded system compared to the 4 000-ton farm system, using chain conveyors and bucket elevators for handling at a 100 tons per hour capacity. This system is designed for medium frequency loading and unloading – three to four times per year. Ducting is unlined, but higher capacity, higher lifespan chain conveyors are used instead of augers.

10 000-ton commercial system: This system is designed for high frequency use – up to 15 times of loading and unloading per year. A 150 tons per hour handling system is installed to increase intake and discharge capacity. This becomes a bottleneck in commercial operations, where the speed of intake and discharge of grain becomes a factor in the willingness of producers to deliver to the silo complex to avoid long waiting times for trucks to be unloaded and loaded.

Silo bags

Silo bag operations can vary between very small and quite large. The financial and operational numbers obtained are targeted towards a small commercial operation or a few producers combining their storage.

Assumptions play a big role in the cost calculations and are as follows:

Assumptions play a big role in the cost calculations and are as follows:

- Life expectancy (site and equipment): Ten years and more.

- Handling capacity: 27 000 tons of maize and 11 000 tons of wheat per annum storage for 60 days per commodity on average.

- Project budgeted as a greenfield project and completely independent (this is seldom the case and some line items could be eliminated, meaning costs will come down).

Outcome

- Capital investment: R6,3 million (this includes all civils, power supply, offices, security and fencing, grading facilities, off-loading and loading [i.e. handling-in and -out], all equipment and vehicles, land is rented).

- Operational expenses are approximately R42/ton (excluding bag costs).

- Cost per 180-ton bag is R5 600 or R31/ton (bags are used only once).

Bunkers and dams

Size matters in the cost per ton but a 20 000-ton facility will cost approximately R20 million or R1 000/ton. Dams can be as small as a few hundred tons. Storing the product is fairly easy but the out-loading is a problem.

There are three main components to the erection of bunker storage facilities, namely the civils to prepare the terrain (it should be level and compacted), the sides or walls, and the trampoline cover. Equipment for loading-in and -out, the weighbridge and grading facilities are separate and depend on the size catered for.

Comparisons and interpretation

Direct comparisons are difficult. Not only is each site different, but service providers consider information to be confidential and a competitive advantage. Although verified and believed to be accurate, all prices are indicative (and excluding VAT).

Silo bags are probably the fastest growing of the three categories, however, the construction of steel silos holds the biggest threat to traditional storage operators. The substantial investment required by producers means that they are committed to own storage for at least five years.

Information on the capacity and growth of on-farm and on-site processing storage facilities is limited and often estimated. No official survey has been conducted. By law, commercial farming operations are compelled to declare grain stored on-farm to SAGIS. However, grain stored and capacity to store are two different concepts.

Agri-businesses have also countered these developments by erecting their own, more cost-effective steel silos and bunker facilities, in addition to their existing (mostly) cement silo structures or when replacement is required. New cement structures are not competitive anymore, therefore the choice is between steel structures and bunkers.

Silo bags, bunkers and dams are generally associated with short-term storage, meaning a couple of months. Some analysts would say as little as three months, but certainly not more than a year. Grain in silo bags is very much dependable on the proper sealing of the grain, depriving it of oxygen.

Any damage to the bags or trampoline cover by rodents, hail or handling (at storage), allowing for oxygen and/or water leakage, could cause damage to the grain. Once stored there is normally no ability to refumigate, while aeration (bunkers) is also normally not possible.

Steel silos and related equipment normally require a higher capital investment. Some of the benefits are:

- Compared to storage costs charged by the agri-businesses, pay-back for the producer is normally achieved in six to nine years.

- The concept of marginal cost makes this attractive for the producer. He already owns the land and normally has services such as electricity and water at hand. Labour can temporarily be allocated, versus full-time in the case of most commercial facilities.

- If the producer’s grain happens to be ‘dirty’, the agri-business requires it to be clean and he will either pay a cost and/or lose out on the trash (broken pits, etc.), a service which could easily be performed at his own storage facilities.

Probably one of the main factors is the logistics (including costs) required to transport grain from the farm to the agri-business storage facilities. Trucks, trailers and drivers often have to be allocated for long periods during the harvesting season. With on-farm storage facilities, grain can quickly be off-loaded and thereafter cleaned (if required) and out-loaded at the producer’s own rate.

It therefore requires a lower investment in trucks, trailers and dedicated drivers. As mentioned, on-farm loading by traders is a common practice and saves the producer transport costs and excessive investment in bulk handling grain trailers.

Agri-business storage costs

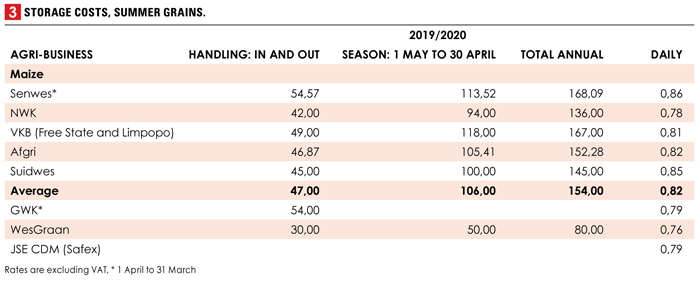

Table 3 outlines the storage costs for the five main agri-businesses (from a storage capacity perspective) as well as GWK and WesGraan (formerly Kaap Agri) and the JSE CDM (Safex) daily rate.

Today, this is a highly competitive business with each agri-business determining its own rate. What makes comparisons difficult is that agri-businesses offer several different packages in terms of which they either load grain on the farm or pay for the producer to deliver the grain to a specific silo. This is mostly related to underutilised silos or when they try to expand their business into neighbouring territories.

Although storage packages differ substantially, a total annual average storage rate of R150/ton for the five large maize agri-businesses has been assumed.

How quickly will the producer recover his on-farm storage investment? This will largely depend on two factors: What portion of the R150/ton remains after running, maintenance and financing costs, and secondly, how many times will the silo capacity be turned around per annum. (Keep in mind the higher the turnover, the less the proportional income per ton, i.e. the R150/ton.)

Financial numbers indicate the producer will recoup his investment in six to nine years. Note that calculations will differ for each operation. Apart from the direct cost associated with the operational costs, there are also what one could call ‘soft costs’ that need to be taken into account, depending on the basis of the comparison.

These include, for example:

- Insurance – the cost of insuring grain in an on-farm facility is often higher, if available at all.

- Grain financing costs at non-Safex registered silos and particularly on-farm facilities are typically higher.

- Marketing costs. Traders are looking at higher margins compared to a Safex registered silo, where – despite no premiums – at least it is easy to quickly sell the product through Safex at the going market price.

- Buyers of grain originating from on-farm storage facilities often penalise the grain with a 1% screening deduction, whether or not this is correct.

Summary

On-farm storage remains a sensitive subject. For many years, all producers were members of their co-operatives, sharing in the benefits. Today, even though ownership of agri-businesses has changed dramatically, there is still substantial goodwill left.

However, in a competitive free market environment, it makes business sense for some producers to erect their own on-farm storage facilities. This trend is likely to continue.

Nevertheless, in a dynamic storage environment, agri-businesses are continuously offering new storage packages. Before taking any decision, a producer should do a detailed cost comparison as it applies to his farming operation and with actual quotes from suppliers.

References

References

- ABC Hansen (2019). Unpublished information. www.abchansenafrica.co.za.

- DAFF (2016). Unpublished Report. Directorate Statistics and Economic Analysis. Pretoria.

- Premier Milling (2019). www.premierfmcg.com.

- SAGIS (2018). www.sagis.org.za

- SAR&H (1923). South African Railways and Harbours Bulletin #54, p 99.