June 2015

WAYNE TRUTER, University of Pretoria,

CHRIS DANNHAUSER, Grass SA,

HENDRIK SMITH, Grain SA and

GERRIE TRYTSMAN, ARC-Animal Production Institute

Integrated crop and pasture-based livestock production systems

This article is the 15th in a series of articles highlighting a specific pasture crop species that can play an imperative role in conservation agriculture (CA) based crop-pasture rotations. Besides improving the physical, chemical, hydrological and biological properties of the soil, such species, including annual or perennial cover crops, can successfully be used as animal feed.

Livestock production systems are in many ways dependant on the utilisation of pasture species, in this case as a pasture ley crop and can therefore become an integral component of CA-based crop-pasture rotations.

It is imperative to identify a pasture species fulfilling the requirements of a dual purpose crop, i.e. for livestock fodder and/or soil restoration. This article focuses on a root forage crop commonly used in the winter season as a crop to improve soil conditions and to provide cover in the winter months of a summer rainfall region.

This annual crop could possibly succeed a perennial grass pasture prior to planting the next season of grain crops.

Raphanus sativus (Radish)

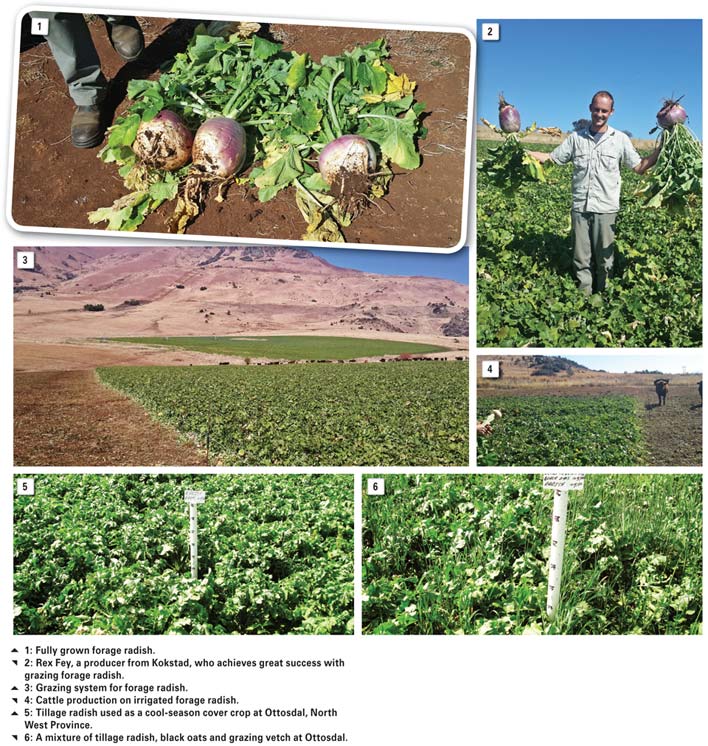

Radish (also commonly known as Japanese, forage or tillage radish) is an annual plant that originates in East Asia and Europe. This forage crop is well-known in the cooler summer rainfall regions of South Africa.

The root component of the crop comprises approximately 50% of the total production, with moisture content as high as 90%. Both the leaf and root material of this crop can be used as young fresh material in winter or carried over to late winter or early spring for fodder.

The most common cultivar is Nooitgedacht, with alternative cultivars such as Samurai, Sakurajuma, Star 1650 and 1651 and a soft leaf cultivar by the name of Sterling.

Agro-ecological distribution

This crop is adapted to the cooler eastern parts of the country; where rainfall is reasonably reliable during January to April. More recently, alternative cultivars are being grown in the western parts of the country as well.

This species is both cold- and drought-resistant, but not tolerant of waterlogged conditions. Radishes grow best when planted early enough to allow six weeks of growth before regular frosts. Radishes are winter hardy plants and are tolerant of light frosts, but generally show injury when temperatures drop below the -0°C.

A suitable rainfall for radish production requires a minimum of 650 mm per annum and it proliferates with a good autumn rain.

Management and utilisation

This crop is best established on sand to sandy loam soils that have a good water holding capacity. Often well-drained clay soils with good water holding capacity are also suitable. The normal planting date is January/February, however, in the cooler eastern Highveld regions, the crop can be planted as early as middle December.

If this crop is planted too early, this species tends to flower prematurely, not allowing sufficient root formation to occur. Late plantings could potentially result in insufficient soil moisture reserves.

When this crop is planted in rows, it is recommended that rows are planted 90 cm apart with plant interspacing of 35 cm – 50 cm from each other. However, when planted as a cover crop, denser seeding rates are used (usually broadcasted) and narrower rows of maximum 50 cm apart are preferred. The seeding rate of 2 kg/ha in rows is advised and 4 kg/ha when sown in a broadcast fashion.

A pre-establishment herbicide, for example Treflan, can be used to control grass and some broad leaved weeds. A product such as Dual can be used to control weeds that emerge once the crop has surfaced. Karate pesticide can be used to control cut worms.

Radish reacts well to a good fertilisation of phosphate (P) and potassium (K) before establishment. Fertilisation should initially strive to obtain at least 20 mg/kg of P and 140 mg/kg of K.

Under dryland conditions 50 kg – 70 kg N/ha are recommended, whereas irrigated conditions will require two applications of 75 kg N/ha each. Many producers and researchers are experimenting with cover crop mixtures that combine radish with legume cover crops that fix N (e.g. grazing vetch) and temperate grasses (e.g. black oats), hence providing more persistent residues.

Soil conservation and health benefits

It is known that when forage radish is grown as a cover crop, it can contribute significantly to:

- Quantities of nutrients and organic matter.

- Improved soil nutrient availability.

- Suppress weeds.

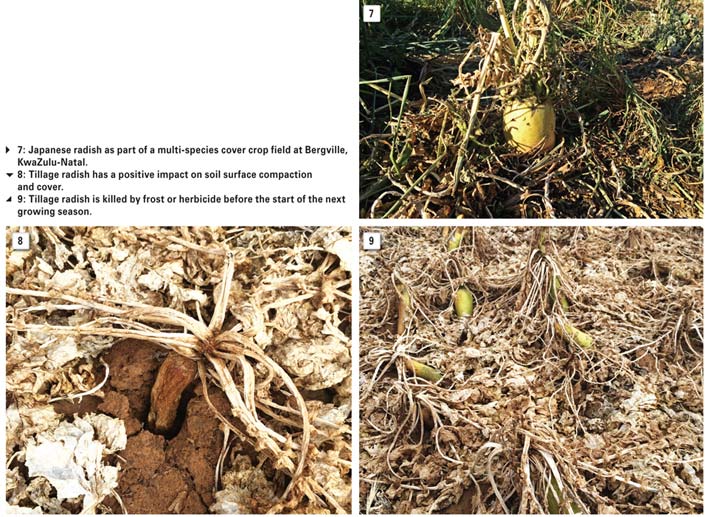

- The alleviation of compaction layers.

In a few research trials it was found that forage radish plots had fewer weeds and almost no remaining cover crop residue, which resulted in warmer, drier soils.

According to Gruver et al. (2014) this crop has been researched extensively to highlight the benefits of radish cover crops on:

Soil structure

- Once radishes eventually die, their large roots desiccate and the channels created by the roots remain open which improves water infiltration and surface drainage.

- Research has also shown that this species’ root penetrates compacted soils extremely well.

Weeds

- High population of radishes can suppress weed growth by overshadowing them.

Nitrate leaching

- Because of their deep root system, rapid root extension and heavy nitrogen (N) requirement, radishes are excellent users of residual N following summer crops, especially if they have been irrigated.

Early spring nitrogen

- Unlike some of the rye crops whose residues decompose slowly and continue to immobilise N for an extended period, radish residues decompose and release N rapidly. If the follow-up crop establishment is planned well, the radish growth can be boosted as if it was planted after a legume crop or initial N fertilisation.

Soil phosphorus and potassium

- Radishes are excellent accumulators of P and K (root dry matter commonly contains more than 0,5% P and 4% K), and research has shown that soil P levels have been higher after a radish crop.

Soil erosion and runoff

- This canopy intercepts rain drops, minimising surface impact and the detachment of soil particles. Even when radishes are killed by a severe frost, a layer of decomposing residue remains on the soil surface up until early spring providing erosion control. In addition, runoff and sediment transport are reduced because of the rapid infiltration facilitated by open root holes.

Soil organic matter

- Literature states that radish biomass is highly decomposable and increases in total soil organic matter (SOM) levels following radish cover crops are unlikely.

Nematodes

- According to the institution EXTENSION (America’s Research Based Learning Network), laboratory bioassays have shown that the residues of radishes and many other cover crops reduce the survival of plant parasitic nematodes such as root knot nematodes (Meloidogyne incognita) and soybean cyst nematodes (Heterodera glycines) compared to unamended controls.

Crop yields

- On-farm comparisons and limited replicated trials reported significant increases in maize and soybean yields following radishes as compared to fallow or other cover crops. These yield increases are likely the combined result of the multiple effects described above.

Management challenges

Radishes have little tolerance of wet soils; therefore waterlogged conditions need to be avoided. Radishes are very responsive to N, and N-deficiency limits their ability to compete with weeds, grow through compacted soil, and perform other potential functions.

Nitrogen deficiencies have been observed when planting after silage or grain corn on sandy soils or on soils that do not have a history of manure application. N deficiencies are also likely when excessively high populations are established. Radishes are only moderately cold-hardy and need about six weeks of favourable growing conditions to produce sufficient biomass to achieve most potential benefits (Gruver et al., 2014)

Animal production aspects

Radish is a good crop for rotational cropping systems, especially after a few years of pasture just prior to planting a grain crop. This crop has very valuable benefits for the dairy production industry.

Often radish is grazed with the help of an electric fence, however, to optimally use most of the plant material, it can be removed from the soil and fed to cattle. Production values of up to 6 tons/ha can be expected with a protein value of 18% – 21% for roots and 20% – 30% for leaves. (Dannhauser, C. and Van Zyl, E. – personal communication).

Conclusion

Choosing radish as a cover crop should be closely linked to problems that producers who are practising conservation agriculture, encounter. One such a problem, especially in our semi-arid cropping areas, is compaction layers within the soil profile, especially within the top 40 cm.

The unique taproot of radish and the ability to elevate this compaction to depth can have an impact on farmer’s decision to use radish as a cover crop. Not only deep compaction layers are elevated, but tubers push the soil up at the surface making it soft and positively influence infiltration.

Due to the fact that residues of radish have a narrow C:N ratio, it is best used in mixtures with crops such as grazing vetch and black oats. This will ensure a proper ground cover before a cash crop is planted. Using radish and radish mixtures during the cool winter months usually deplete soil water that could influence or delay initial planting dates of a following summer cash crop due to a dry soil profile.

For more information, contact Dr Wayne Truter at wayne.truter@up.ac.za, Prof Chris Dannhauser at admin@GrassSA.co.za,Dr Hendrik Smith at hendrik.smith@grainsa.co.za or Mr GerrieTrytsman at gtrytsman@arc.agric.za.

References

Gruver, J., Weil, R., White, C. and Lawley, Y. 2014. Radishes – a new cover crop for organic farming systems.

Publication: June 2015

Section: On farm level