June 2018

DR GODDY PRINSLOO, ARC-Small Grain, Bethlehem

Aphids are important transmitters of plant viruses attacking different crops. Knowledge of their migration and seasonal presence could enable us to make decisions on when to control the aphids to prevent virus transmission to crops.

Aphids are important transmitters of plant viruses attacking different crops. Knowledge of their migration and seasonal presence could enable us to make decisions on when to control the aphids to prevent virus transmission to crops.

A suction trap network was started by potato producers in 2005, who have since 2013 been joined by the wheat industry. The network currently consists of 13, 12,2 m high suction traps in the major potato and wheat production areas of the country.

These traps continuously collect all flying insects on a weekly basis. In collaboration with the Department of Zoology and Entomology at the University of Pretoria, all aphids are sorted, counted and identified and data made available on a weekly basis to producers via the internet.

One trap was moved to Cookhouse during May last year, since the producers in that area were complaining about the presence of barley yellow dwarf virus on wheat (Photo 1). This became the first suction trap to monitor insects in the Eastern Cape.

At the same time, a 1,8 m high suction trap was installed on a farm near Hofmeyr in the same province, to get an indication of aphids infesting crops in that area.

Aphids migrating on air currents

It is known that aphids migrate between areas on air currents moving at or above 12 m from the soil surface, hence the height of the suction traps. Therefore, aphids feeding on a crop infected with a virus could migrate to another area within hours and when landing on a suitable crop, could transmit the virus.

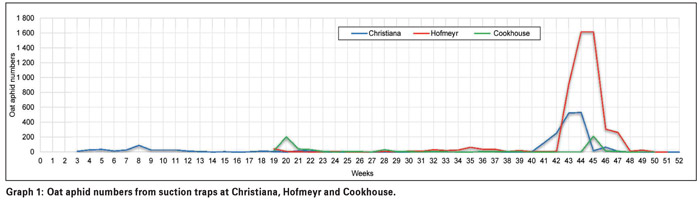

If we look at the aphid number peaks in the different areas there seem to be coincidences between traps. For example, from mid October last year (week 41 to week 44), an oat aphid peak was observed in the Christiana trap (Graph 1).

The small trap in Hofmeyr showed a huge peak which overlaps with this period (week 43 to week 45), while the Cookhouse trap reveals a peak during week 45.

Producers in the Eastern Cape were cutting their oats during this period for silage purposes, which forced many aphids from the crop and locally moving aphids are easily trapped by the small trap.

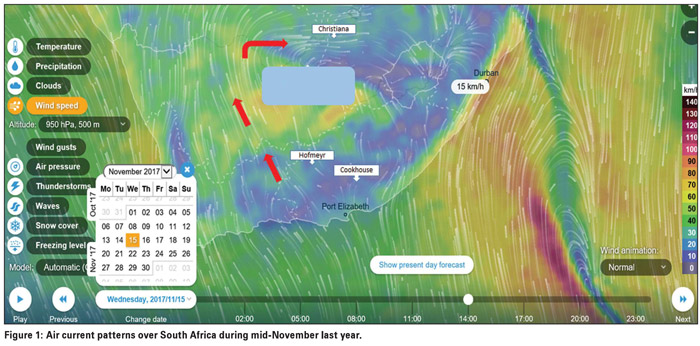

A detailed look at air current patterns during this period revealed a possible explanation for these aphid numbers to peak at almost the same time. During the week of 15 November last year, air currents were heading from the south inland over the country in a slight north-western direction passing over Hofmeyr (Figure 1).

In the Orange River region of the Northern Cape, these currents made an almost 90° turn in an easterly direction, heading all the way over the Kimberley, Christiana and Vaalharts areas (Figure 1). Wind speed at that time was 40 km/h to 60 km/h, which may have carried aphids within a day to the Christiana area.

However, since air currents change every day, the opposite could also be true, carrying aphids to different production areas in short times and thus enabling the spread of plant viruses between regions. For a better understanding and forecasting of aphid migration, the physical on-farm activities and air current patterns should also be considered in the analysis of aphid flight data.

For further information contact Dr Goddy Prinsloo at prinsloogj@arc.agric.za or 082 875 3401.

For further information contact Dr Goddy Prinsloo at prinsloogj@arc.agric.za or 082 875 3401.

Publication: June 2018

Section: On farm level