April 2015

MOSES RAMUSI and BRADLEY FLETT, ARC-Grain Crops Institute

Downy mildew is caused by the soil-borne fungal pathogen Plasmopara halstedii, which occurs in the major sunflower production areas of South Africa.

Previously, minor downy mildew epidemics have been recorded in the Rustenburg, Brits and Potchefstroom areas of the North West Province of South Africa in commercial fields and research plots.

Epidemics are reliant on infection by primary inoculum from infected seed or soil. Yield losses can be low to moderate, depending on the percentage of infected plants and their distribution within the field.

Epidemiology of the disease

The causal pathogen, P. halstedii, can survive for up to ten years in contaminated soil as oospores. These oospores germinate when soils are cool, accompanied by the presence of saturated water. These oospores form zoosporangia, which will give rise to mobile zoospores, which move through the soil.

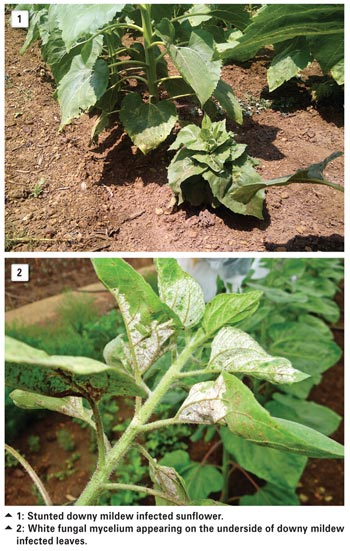

Initial infections occur when these zoospores infect sunflower seedlings. Infected plants usually die during the early growth stages, but if plants do survive, it still grows and generally produces white zoosporangia on the underside of the leaves prompting secondary infection.

This is not always the case as dwarfed plants showing normal symptoms of downy mildew have been observed to not have the typical leaf lesions and spore production on the underside of the leaf.

Symptoms of the disease

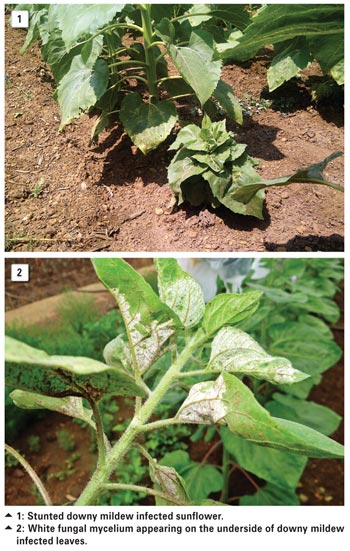

Early infected plants usually die, causing reduction in plant stand and thus resulting in bare patches in the field. This has often been the case where epidemics in South Africa have been recorded. Systemically infected sunflower plants are usually dwarfed or stunted (Photo 1) with shortened internodes and the sunflower head pointing straight upward.

Early infected plants usually die, causing reduction in plant stand and thus resulting in bare patches in the field. This has often been the case where epidemics in South Africa have been recorded. Systemically infected sunflower plants are usually dwarfed or stunted (Photo 1) with shortened internodes and the sunflower head pointing straight upward.

Surviving stunted, infected plants show a thickening and yellowing of the leaves, which usually borders the veins of the leaves, but can also be present on the whole leaf. White fungal mycelium and spores appear on the underside of these leaves (Photo 2).

Disease control

Planting of resistant hybrids is recommended in areas where downy mildew is a problem. Resistance is often race-related, and to determine adequate resistance, a survey of sunflower downy mil dew infected plants is necessary.

This will enable us to determine which P. halstedii races occur in South Africa and which resistance genes need to be included into local cultivars.

Volunteer sunflowers serve as alternate hosts of the downy mildew causal pathogen; therefore, proper weed control in crop rotation sequences can help reduce the disease. Crop rotation is important because it prevents disease build-up in the field by interfering with the life cycle of the disease. However, crop rotation will have a minimal impact on downy mildew as the disease can survive in the soil for more than ten years. Crop rotation programmes to reduce downy mildew need to be carefully planned.

The pathogen is seed- and soil-borne, therefore, fungicide seed treatments can help minimise the disease. In the USA, metalaxyl resistance is common and known to reduce seed treatment efficacy. Metalaxyl resistant races of the pathogen have yet to be recorded in South Africa so we assume at this point that metalaxyl is effective for controlling infections. Alternate seed treatment fungicides are used in the USA to counter this resistance. Foliar fungicide applications are neither effective nor economical.

The authors request that should any producer observe the abovementioned symptoms, to please contact them. They require isolates for race determination studies to fully understand which resistance genes are effective to control this disease in local breeding programmes.

Contact them at RamusiM@arc.agric.za or FlettB@arc.agric.za.

Publication: April 2015

Section: On farm level