ARC-Grain Crops,

Potchefstroom

The productivity of maize in South Africa is influenced by various factors, including abiotic and biotic stresses and their interactions as well as monocropping. Abiotic factors include poor soil fertility, drought and heat stresses.

Although soybean production has increased significantly since 2008, maize monocropping remains a widespread practice in many farming systems, resulting in a decline in soil fertility and nutrient imbalances – and ultimately lower yields. Several factors favoured continuous cropping of maize over crop rotation, including relatively high and stable net returns from maize compared to that of alternative crops and relative ease of production. Crop rotation of maize with grain legumes has, however, been reported to have a positive effect on soil nitrogen (N) and maize yields.

Crop rotation

Grain legumes are arable crops of the Leguminosae family, cultivated primarily for their grains and used either for human consumption or for animal feed. Legume crops have the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen, which can increase the productivity of a cereal-based cropping system. Therefore, grain legumes like cowpea (Photo 1) and soybean (Photo 2) do not need any N fertilisation for their growth. There is a wide range of grain legume crops and varieties with different growth durations and other characteristics in South Africa. Different legume species in a crop rotation can affect nitrogen fixation and its residue in the soil differently. This implies that legumes have a potential position in a wide range of farming systems and can reduce high utilisation of inorganic N fertiliser.

Soil nutrient availability is one of the most important factors for crop growth. Inorganic fertilisers have been used for crop production worldwide for decades, which have been estimated to reach 200 million tons annually by 2050 in order to increase crop yields to meet global demands. However, their injudicious use can have an adverse impact on crops and the environment. Literature has shown that inorganic N in farming systems is usually applied at much higher rates than needed to achieve high maize crop yields, leading to negative environmental impacts. Soil acidification is one common hazard, especially in coarse-textured soils. Application of the right quantity of phosphorus (P) on legumes can improve N fixation. It is important to remember that the addition of P and potassium (K) is crucial on cowpea and soybean cropping systems since they are heavy feeders of those elements.

The research

The research

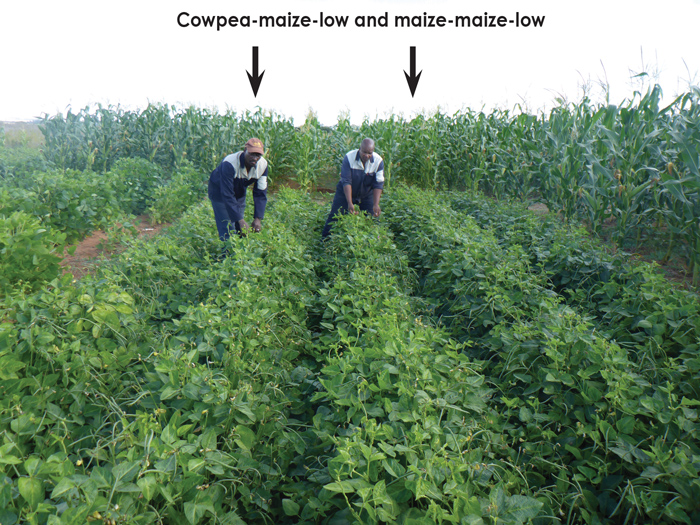

A study was conducted at Lichtenburg from the 2016/2017 to 2018/2019 seasons to investigate the impact of cowpea-maize and soybean-maize on soil nutrition and maize grain yield as compared to continuous maize under two fertilisation levels referred to as high (H) and low (L). The high fertilisation level in maize was equal to NPK fertiliser to achieve 4 t/ha maize grain yield, with the low fertilisation level equalling half those amounts. Cultivars used were: maize (BG 5685 R); cowpea (Bechuana white) and soybean (PHB 96T06 R). The trial site is characterised by an Avalon soil form with sandy loam texture and average annual rainfall of about 580 mm. Soil sampling and analysis were done using standard procedures to compare nutrients under legumes and maize plots. From season two, maize data were collected to determine the grain yield of maize following a legume and continuous maize.

Results

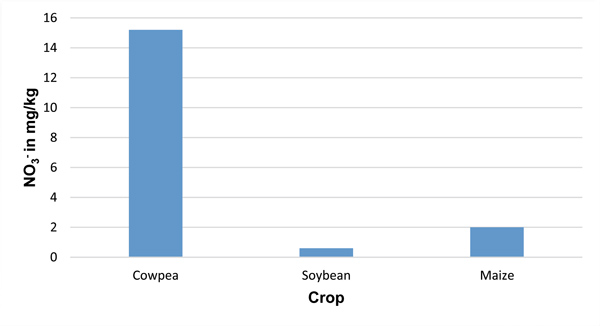

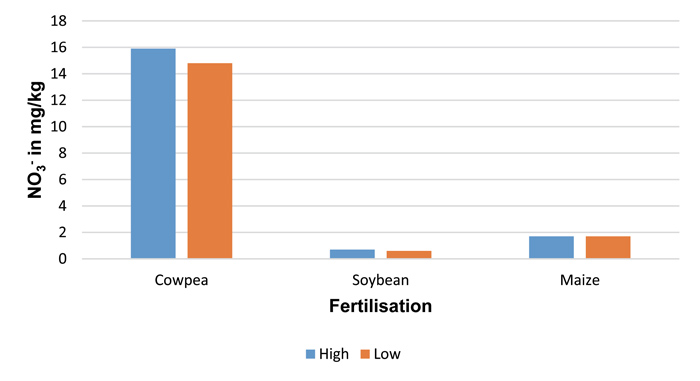

Results given are part of a larger study of three seasons. In season one, rotation had a significant impact on nitrate (NO3-) (NO3– is immediately available to the crop) with cowpea plots giving higher nitrogen than either maize or soybean (Graph 1). No clear differences on NO3– between maize and soybean were observed, although soybean recorded the lowest. The crop x fertilisation interaction also had an impact on NO3– with cowpea plots at either high or low fertilisation giving higher NO3– than other treatments (Graph 2). No clear differences were observed between either high or low fertilisation maize or soybean, although soybean had the lowest NO3-.

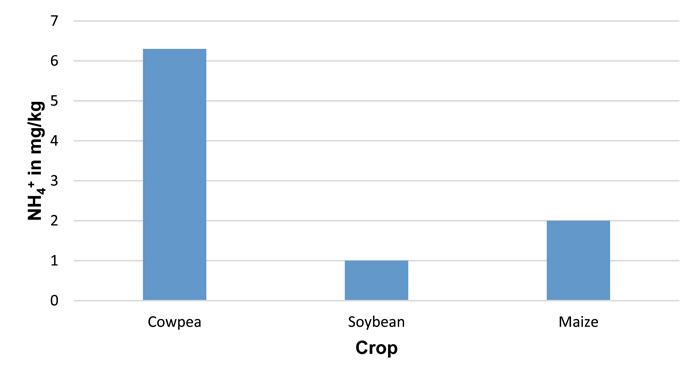

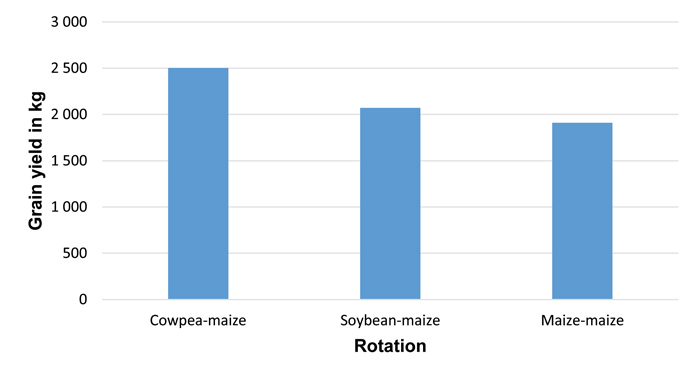

Rotation had a significant impact on ammonium (NH4+) with cowpea plots giving higher nitrogen than either maize or soybean plots (Graph 3). Soybean plots had the lowest NH4+. In season two, crop rotation had a significant impact on grain yield with continuous maize giving lower yield as compared to maize following either cowpea or soybean (Graph 4). Fertilisation level had no significant impact on both N (NO3– and NH4+) and yield (data not given). Similarly, other nutrient elements like P and K were not significantly affected by either rotation or fertilisation level (data not given).

These preliminary results show that cowpea has the inherent ability to leave some of the N it fixes in the soil even better than soybean, benefitting a subsequent cereal crop like maize. Although soybean fixes substantial quantities of N (159 kg N/ha to 227 kg N/ha) as compared to that of cowpea (11 kg N/ha to 201 kg N/ha), low residual N observed on soybean plots could be because soybean is fairly N neutral. This means that roughly the same amount of N that is fixed by soybean is removed by the grain, also known as the nitrogen harvest index (NHI).

It is also important to note that soybean seed should be inoculated with rhizobium bacteria (Bradyrhizobium japonicum) for effective N fixation. Considering the amount of N fixed by both cowpea and soybean, the overall low soil residual quantities in this study suggest that the majority of N is removed when grains and plant residues (stover) are removed from the field after harvesting.

Higher yield of maize following either cowpea or soybean compared to maize irrespective of residual N, could suggest that the legumes’ benefits to the subsequent crop in rotation may go beyond nitrogen credits. The non-N effects of legumes include improvement of the soil and environment of subsequent cereal crops resulting in healthy roots. This could be due to the quality and quantity of root exudates from different species released into the rhizosphere.

In conclusion, these results confirm that the full benefit of legumes in improving soil N can only be realised when plant residues are not removed from the field. However, the speed at which N in stover is available, will always depend on the rate of mineralisation by responsible soil microbial and enzyme activities. Legumes in rotation with maize do not only provide N, but can also reduce maize root pathogens, thus improving root health.

References

- Lobulu, J, Shimelis, H, Laing, M & Mushongi, AA. 2019. Maize production constraints, traits preference and current Striga control options in western Tanzania: farmers’ consultation and implications for breeding. Soil and Plant Sciences, 69 (8), 734 – 746.

- Nel, AA & Lamprecht, SC. 2011. Crop rotational effects on irrigated winter and summer grain crops at Vaalharts. South African Journal of Plant and Soil, 28: 127 – 133.

- Ronner, E & Franke, AC. 2012. Quantifying the impact of the N2Africa project on Biological Nitrogen Fixation.