May 2016

SHAWN PHILLIPS, research analyst: Glacier by Sanlam

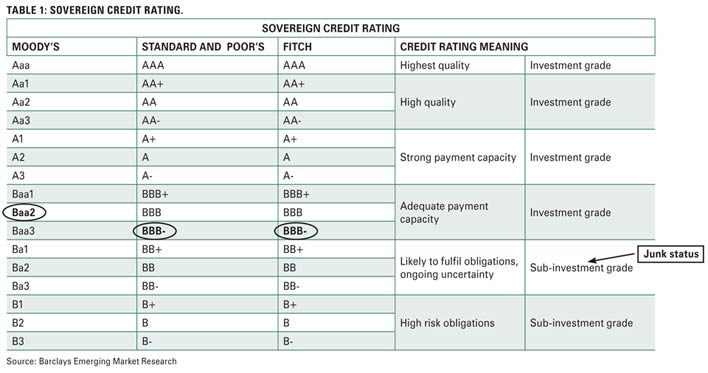

A lot has recently been said in the media regarding the possibility of whether South Africa will be downgraded to ‘junk status’ by the respective rating agencies, namely Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s and Fitch.

Emphasis has been placed on the implications for our stumbling economy, the government, corporates, consumers and what the government is required to do in order to avoid a possible downgrade. This article will focus on understanding what a sovereign credit rating is and what ‘junk status’ means for South Africa and its citizens.

What is a sovereign credit rating?

A sovereign credit rating expresses the risk that a country will be unable to meet its financial commitments, in terms of repaying interest payments and the debt principal on a timely basis.

Essentially, a sovereign credit rating is aimed at providing a relative ranking of a country’s overall credit worthiness. Moreover, the respective rating agencies mentioned above utilise various measures that allow them to gauge a country’s social, economic and political position in order to determine the probability of a country defaulting on its repayments. Table 1 below depicts the sovereign credit ratings by the respective rating agencies.

As it stands, Moody’s has rated South Africa as a Baa2 rating which is two notches above sub-investment grade (‘junk status’), while Standard and Poor’s and Fitch have rated South Africa as BBB-, which is one notch above ‘junk status’.

An important but unappreciated distinction between the sovereign credit ratings is the rating between the foreign currency denominated debt and the local currency denominated debt.

Distinguishing between our local currency debt rating and foreign currency debt rating

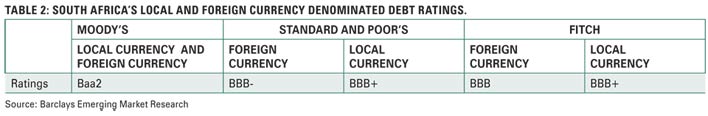

Foreign currency denominated debt is characterized as debt that is issued in a currency other than the sovereign’s own currency (i.e. South African issued government bonds in US$, yen or euros), while local currency debt is debt that is issued in local currency (i.e. ZAR). Table 2 displays South Africa’s local currency and foreign currency debt ratings by the respective rating agencies. Furthermore, it is important to note that it is South Africa’s foreign currency denominated debt rating that is in the firing line in terms of a possible downgrade to ‘junk status’.

As seen in Table 2, Moody’s has one rating which applies to both the local currency and foreign currency denominated debt, while Standard and Poor’s and Fitch distinguishes between South Africa’s foreign currency and local currency debt ratings.

Moody’s rating for South Africa is two notches above ‘junk status’, and the Standard and Poor’s rating for South Africa’s foreign currency is one notch above ‘junk status’, while its rating for South Africa’s local currency is three notches above ‘junk status’.Fitch’s rating for South Africa’s foreign currency is two notches above ‘junk status’, while its rating for South Africa’s local currency is three notches above ‘junk status’.

In terms of the respective rating agencies, Standard and Poor’s’ is of great concern as South Africa’s foreign currency debt rating is only one notch above ‘junk status’, while it is two notches above ‘junk status’ for both Fitch and Moody’s.

What does a downgrade imply for South Africa and its citizens?

The bottom line is that if South Africa were to be downgraded to ‘junk status’ in terms of its foreign currency debt, then it will cost South Africa more to borrow money in global markets. Currently, South Africa has a budget deficit, implying that the government spends more than it earns, whereby the deficit is funded via loans from large international bodies through issuances of South African government bonds. Furthermore, South African consumers are highly indebted and continue to finance their lifestyles through debt and the cost of servicing this debt will become more expensive.

Generally, as seen in past sovereign downgrades, the direct impact is usually felt in the bond and fixed income market through rising interest rates. A secondary shock will generally be felt in the sovereign’s currency, as it weakens against other major currencies. This could also have a negative impact on the equity market as investors deem the sovereign’s assets to be more risky.

Is a downgrade likely?

Yes, a downgrade is likely across both the local currency and foreign currency debt rating, however in the case of Standard and Poor’s, it will only be our foreign currency debt rating that will be considered as sub-investment grade. For Moody’s if a downgrade were to take place, then South Africa’s local currency and foreign currency debt rating will be one notch above ‘junk status’, while if a downgrade were to take place for Fitch our local currency debt rating will be two notches above ‘junk status’ and our foreign currency debt rating will be one notch above ‘junk status’.

Moreover, it is important to note that institutions that offer credit in a specific country cannot have a higher sovereign credit rating than the sovereign itself, implying that banks and corporates will be downgraded along with its respective sovereign. For a country like South Africa, what matters is our local currency debt credit rating as the bulk of our debt is domestically issued (i.e. ZAR).

Is this the end of the road for South Africa?

No, South Africa’s government bonds have already priced in most of the bad news associated with a downgrade. However, it is difficult to say what impact a knee-jerk reaction by investors will have on the bond and fixed income markets. Lower bond yields internationally imply that South African bonds will still remain attractive for investors on a relative basis.

We will only be at the ‘end of the road’ if South Africa’s local currency debt ratings were to become sub-investment grade (i.e. ‘junk status’) and then only will our bonds be in jeopardy in terms of inclusion in the respective global bond indices.

Publication: May 2016

Section: Focus on