research coordinator and agricultural econo-mist, Grain SA

Luan van der Walt,

Luan van der Walt,economist, Grain SA

Bread is an important staple food in South Africa and plays an integral role to ensure national food security. Consumers for the most part do not buy food directly from producers and the price consumers pay for food is exceedingly higher than what producers receive for the raw commodity.

This article seeks to highlight the percentage contribution of wheat producers to the price of a loaf of white bread sold at retail stores. The wheat producers’ share in the retail price of white bread is scrutinised to demystify a common misconception that producers are responsible for high bread prices.

Background on the wheat price

The price of wheat for a South African buyer is normally determined by the international wheat price, the exchange rate and the local supply and demand for wheat. South Africa is not self-sufficient in the production of wheat and therefore approximately 50% of its local consumption is imported.

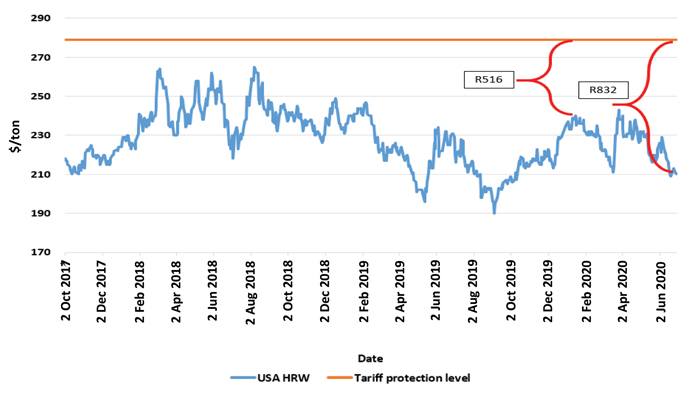

South Africa’s dependency on imported wheat increased over time and hence the domestic price for wheat, as reported by Safex, tends to be close to import parity. The wheat import tariff is crucial when local wheat production is considered, as it provides a support-base to domestic wheat prices and to some extent supports wheat producers’ profitability. At the moment the tariff is R516,61/ton (announced 3 March 2020) and is expected to increase to R832,07/ton due to a decrease in international wheat prices. The new tariff was triggered on 24 March, but has to date not been announced. It is important to note that the import tariff has been priced into the calculations below.

Purpose and functioning of the wheat import duty

Purpose and functioning of the wheat import duty

The purpose of the wheat import duty is to keep local wheat prices in line with the international reference price of $279/ton. The reference price of $279/ton was approved by the International Trade Administration Commission (ITAC) in the previous revision of the wheat import duty. This level was therefore identified as a suitable level to get protection for the local wheat producers without having a negative effect on local consumers.

Graph 1 is a practical explanation of the purpose and functioning of the wheat import duty. During January 2020 the international wheat market traded at around $240/ton and the wheat import duty was triggered at a level of R516/ton. This is the amount (given the exchange rate) that is needed to keep local prices more or less in line with the international reference price. The international wheat market is currently trading at around $210/ton. The lower international wheat prices resulted in a need for a higher import duty in order to keep the local wheat prices more or less in line with the international reference price as was approved by ITAC. The abovementioned explanation of the purpose and functioning of the wheat import duty clearly indicates that there is no direct correlation between the change in wheat import duty and the local wheat price. (The local wheat price does not increase directly as a result of the increase in the import duty.)

Source: Grain SA, SAGIS

How much wheat in a loaf of white bread?

In order to calculate the difference between the real farm value and real retail value, the following norms are used. To bake a 700 g loaf of white bread, an average of 480 g of flour is needed. Again, in order to mill that 480 g of flour, 588 g of wheat is required. Thus, approximately 1 700 loaves of white bread can be produced from 1 ton of wheat.

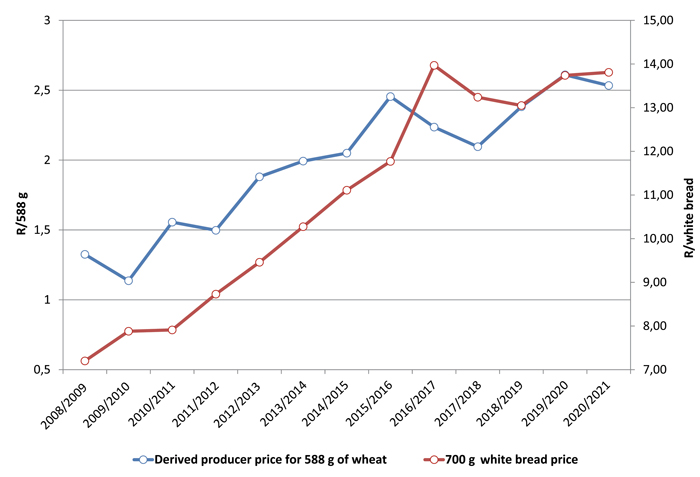

The price consumers pay for bread versus the price producers obtain for their wheat (Graph 2) presents a derived wheat producer price required to produce 588 g of wheat for one loaf of white bread. The derived producer price is calculated by the average annual Safex price for each marketing year and deducting the relevant costs, such as the location differential as well as handling and storage costs.

Source: Grain SA, Stats SA

Graph 2 compares the derived producer price for 588 g of wheat against the annual average price of a 700 g loaf of white bread in a retail store. During the 13-year period, wheat producer prices declined five times (red circles), whereas a predominantly increasing trend is observed when the average annual bread price is considered. Bread prices continually increased from 2008/2009 to 2016/2017 (eight-year period) until its first decrease in 2017/2018. This accentuates that producers did not share in or even contribute to these higher retail prices. In general, raw wheat price movements were in many instances not the main contributing factor to the increase in the bread price, even with the additional import wheat tariff effects.

Wheat producers’ percentage share of retail white bread price

While input prices increased for both producers as well as retailers, the producer’s share of the consumer’s rand remained relatively stable or even decreased in some years. Between 2008 and 2020, a wheat producer’s share of a 700 g loaf of white bread fluctuated between 14% and 21% (calculations include the wheat import tariff). This implies that when a consumer bought a loaf of white bread, the raw material (wheat) simply cost R2,53 in comparison to the total bread loaf price of R13,81. For example, if the loaf consists out of 21 slices, the producer’s cost for that bread is only four slices, while the rest of the wheat-to-bread value chain is responsible for the additional cost (Figure 1).

Conclusion

It is imperative to be made aware that the increase in bread prices is not necessarily linked to an increase in the wheat import tariff or wheat prices, but rather can be attributed to costs further down the value chain. The wheat import duty has a specific function as explained earlier. The main purpose thereof is to keep the local wheat prices more or less in line with the international reference price of $279/ton, the level which assists the profitability of local producers without placing an additional burden on local consumers.

The profitability of the local wheat producers and the growth towards self-sufficiency in terms of local wheat supply and demand are very important aspects for the local wheat market. Uncertain times, such as the global pandemic, have taught the world markets a lot of lessons. In terms of wheat specifically, Russia announced export restrictions for the rest of the marketing season. Although the current restrictions from Russia did not have major implications for the local market, events like that could cause major disruptions for a country such as South Africa. Having the ability to be self-sufficient in terms of local supply and demand, is a massive value for any country. Therefore, it is important to keep the fundamental aspects of the market in place during all times to ensure long-term sustainability.