In order to better comprehend the impact of rail cable theft on the maize industry, the importance of the maize export programme and the necessity of an efficient maize value chain have to be understood as well.

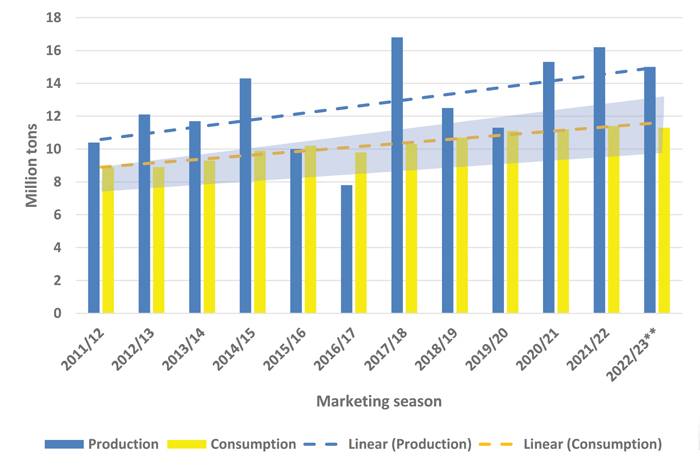

Near record production in 2021

Producers achieved a near record maize crop in 2021, amounting to 16,2 million tons. This has only been surpassed by the record of 16,8 million tons produced in 2017. Annual production has and will probably remain volatile. By comparison, in the drought year of 2016, only 7,8 million tons were produced – not nearly enough to meet the local demand.

During the past twelve years, local demand has remained stable and has grown steadily from 8,9 million tons in 2011 to 11,4 million tons in 2021. This signifies an average growth rate of 2% per year. Some analysts say that one should add the cross-border Southern African demand to this number. Even if one does, it is worth noting that it only comprises about 6% to 7% of South Africa’s local demand.

Accumulation of stocks

As a result of the large 2021 crop, South Africa suddenly found itself in a position where it was likely to accumulate a large exportable surplus. Since the drought of 2016, deep-sea exports had varied between 0,2 million and 1,7 million tons per year, while in the same period, exports to Southern African countries had varied between 0,6 and 1,4 million tons. With another good crop year in 2021 following on that of 2020, and with sufficient carry-over stock levels of 2,1 million tons as at 1 May 2021, the focus quickly shifted to deep-sea exports. Initial predictions at the time showed that South Africa had an exportable surplus of about 4 million tons, after provision had been made for 2 million tons of carry-over stock on 30 April 2022. This was more than the logistical capabilities of the South African harbours.

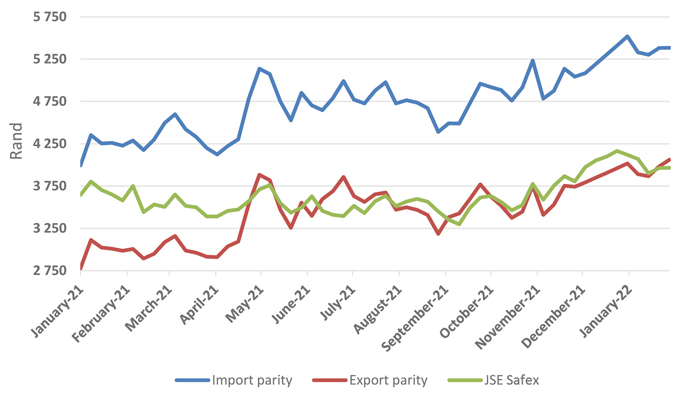

Declining market prices to facilitate export deals

The market was quick to recognise this and since about April/May 2021, prices have traded lower to export parity and below. This enabled the traders to book export deals.

Traditionally the optimal period for South Africa to export maize is May to October, before the new crop in the United States is harvested and prices come under pressure. However, partly due to prices trading at export parity in South Africa and higher international prices, exports were booked into early 2022. The latest predictions are that South Africa will have deep-sea exports of about 3,0 million from May 2021 to April 2022. May 2022 signals the start of the new marketing year, as well as the start of the new harvest. All available vessel slots have already been booked until April 2022 and are included in the above prediction. This will generate approximately R14 billion in foreign exchange for the country.

High international prices combined with improved production technology and high yields in 2021, meant that many producers in the eastern Free State, parts of KwaZulu-Natal and southern Mpumalanga could sell for the export markets and still make a profit. The average yellow maize JSE/Safex July 2021 contract price from 1 June to 22 July 2021 was R3 317/ton. The average yellow maize yield for the Free State according to the Crop Estimates Committee (CEC) was 5,95 t/ha. If the Grain SA production cost survey for 2020/2021 is used to substitute these numbers in the calculations for the eastern Free State, producers would have made a profit of R692/ton. This includes the Grain SA provision for overheads of R398/ton and excludes any premiums achieved on the export lines.

Calculating export parity

Key elements in determining whether traders could profitably execute deep-sea contracts are (1) where the maize is located; (2) the premiums payable for suitable locations; and (3) ease and cost of moving the grain to Durban. Of course, there are other factors, but traders either have little or no control over factors like market prices or the exchange rate. Then there are factors of which the cost impact is fairly constant, like the terminal cost to load a vessel. This compares to the above three factors where trading experience and skills may make a difference in concluding a successful deal.

Map of main and branch lines

Maize for exports is normally sourced in KwaZulu-Natal, the eastern Free State and southern Mpumalanga. The cost and efficient execution of transporting maize to Durban form a very important part of the export calculation. The objective for the trader is to source maize close to or on the main transport routes to Durban. It is worth paying a premium for this maize. The saving in transport cost, availability of trucks, transport time to Durban, efficiencies at the export silos, backloads for transporters, et cetera, more than compensate for the premium. These areas also traditionally have a well-developed rail transport network. The latter has also been well maintained in comparison to other areas. The area and silos most popular and operationally active are depicted in Figure 1. Note that the main line between Bethlehem and Harrismith and the three branch lines and the silos on these lines are the most sought after.

Cost and efficiencies of transport

Why still load by rail? Silos were designed to off-load producer deliveries (intake) while simultaneously loading rail wagons for out-loading. If the silos out-load by road, they have to stop the producer deliveries. One can also load many more rail wagons in a much shorter period of time than road trucks. It is also much more efficient for the harbour terminals to off-load rail wagons than road trucks. Moreover, road trucks cause huge congestion in the harbour area and the city of Durban as well as increasing the cost of maintenance of the roads.

With 220 000 tons exported every month and an 80/20 split in road supply versus rail, approximately 5 100 interlink road trucks use the N3 to off-load in Durban harbour every month. Lastly, electrical locomotives are significantly cheaper than road trucks powered by diesel. The rate per ton by rail wagon from say Reitz to Durban, is approximately R255/ton. This compares to the current road truck rate of approximately R420/ton.

Export terminals

South Africa currently has three operational import/export bulk grain terminals, all situated in Durban. These are Agriport, belonging to Transnet Port Terminals (TPT), a state-owned entity, and two terminals belonging to South African Bulk Terminals (SABT), namely SABT Island View and SABT Maydon Wharf. SABT is a subsidiary of the Bidvest Group, a public-listed company. Given draft and silo capacity restrictions, for the purpose of exports, SABT Island View is the only terminal that can handle a supramax vessel of 50 000 to 55 000 tons. If a vessel loads at Agriport, it normally loads about 40 000 tons and then ‘tops up’ at Island View. SABT Maydon Wharf is mainly used for imports, but does load exports – in which case it also has to ‘top up’ at Island View. The draft at Island View is 12,2 m, at Maydon Wharf it is 9,5 m and at Agriport it is 10,0 m.

Rail capacity at terminals

SABT Island View can handle 96 rail wagons or 4 224 tons per day, five and a half days per week, averaging out to approximately 23 000 tons per week. Agriport can theoretically handle 48 wagons a day if it cuts back on road. For now, Agriport has requested Transnet Freight Rail (TFR) to supply it with a train a day (or 32 wagons), which it will off-load in combination with road. Due to refurbishments in 2021 and lack of availability of rail wagons, it did not receive any wagons during last year and is still negotiating with TFR for this year. If Agriport is left aside, in ideal circumstances SABT should receive approximately 92 000 tons per month when the export programme is running at full capacity, as it has been since May 2021.

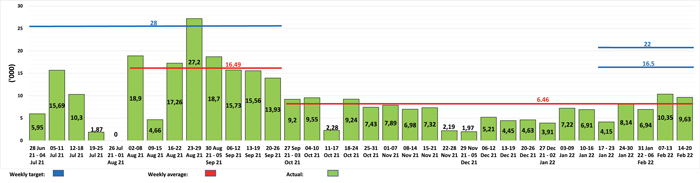

Impact of cable theft

Looking at the grain loaded by TFR in the period 2 August to 26 September 2021, TFR averaged 16 500 tons per week. The export programme at that time was already in full swing. Not quite what SABT can handle, but still a very reasonable volume. This changed dramatically when the cable theft started in September 2021. Average volumes have declined by 61% to 6 500 tons per week since then.

The direct cost, based on the transport rate differential referred to above, amounts to R6,6 million per month. This is the difference between what was achieved by TFR in August and early September 2021, and the average since then. However, to get the full picture, the cost of lost TFR business on the potential volumes (the 92 000 tons per month minimum) versus the actuals of 26 000 tons per month (on average since September 2021) should also be calculated. The difference in tons would then be 66 000 or R10,9 million in additional transport costs per month. In the latter calculation, not all inefficiencies should be attributed to cable theft, but also to factors such as locomotive breakdowns, connections between sidings and branch lines as well as shortages of locomotive drivers. For example, Afgri has 70 silos with rail sidings. The sidings have all been maintained, but only 30 have operational connections with the branch lines. The building of lines into sidings is a TFR responsibility in conjunction with the siding owner. Of the 30, only 14 have been used in the last six years.

Cable theft has also brought enormous maintenance cost implications for TFR. It costs approximately R500 000 in material to repair a kilometre of stolen cable. About 60 km of cable have already been stolen, meaning that roughly R30 million on material and another approximately R12 million have been spent on maintenance teams, according to TFR. Sub-stations are also sabotaged so that the line goes dead for the criminals to cut it more easily. The situation is so dire that due to repeated incidents after repairs to the line, TFR has been forced to de-electrify the line between Bethlehem and Harrismith, withdraw the electric locomotives, and replace them with old diesel locomotives. Loaded wagons are now taken to Harrismith by diesel locomotives, where they are handed over to electric locomotives, while the diesel locomotives go back to fetch more loaded wagons. Collectively everything leads to more inefficiency.

Outlook for 2022

The longer-term outlook for South African deep-sea maize exports has turned positive. The reason is that with modern production technology, the average growth in production exceeds the average growth in demand (see Graph 3). Barring a serious drought, it is likely that going forward, South Africa will be in the export market every year.

Also, the deep-sea export outlook for the new season starting 1 May 2022, is very promising. This is despite heavy rains and flooding experienced by producers in December 2021 and January 2022. Seven SACOTA trading members surveyed on 26 January 2022, on average were predicting a total maize crop of 15,01 million tons, although March 2022 is still an important growing month (range 14,5 million – 15,5 million tons). Export slots are already fully booked for May and June 2022 and indications are that some traders have already secured deals for July 2022 and beyond. If the 500 000 tons that should go out in May and June are deducted, as well as local and Southern African demand, and provision for ending stocks is made (30 April 2023), South Africa is likely to remain with an additional exportable surplus of 2,5 million tons.

Collaboration between SACOTA, TFR, Grain SA and industry

There is a silver lining to the dark cloud. In September 2021 SACOTA initiated a semi-monthly meeting with TFR. It also organised an industry planning workshop in January 2022. The main outcome was that TFR has agreed to engage with industry on opportunities for collaboration in combatting the cable theft issue. Furthermore, TFR internally approved additional security measures in February.

In Graph 3 an uptick in TFR performance during February can already be seen. Thanks also to the initiative of the Grain SA CEO, Dr Pieter Taljaard, a security meeting has been scheduled to take place with the farmer security control rooms in the Bethlehem area during March. TFR’s security division and the South African Police Service will participate and take the lead in combatting cable theft.

Given the positive outlook for grain exports, the contribution grain exports can make to rural employment and development, and the need for an efficient and functional export value chain, the industry owes it to South Africa and its people to ensure that there is an efficient rail system.