ARC-Small Grain,

Bethlehem

The invasive ability of an insect in a specific area will be determined by establishment success and rate of spread, but also by environmental factors that will influence the adaptation and spread within the geographic range of establishment. Russian wheat aphid (RWA) possesses many of the features that define a ‘good invader’ and as a result became a global threat to wheat production.

RWA samples were collected during the wheat-growing season in South Africa from August 2020 to January 2021. There are two main dryland wheat production areas in South Africa where RWA commonly occurs, the Western Cape (winter rainfall area) and the Free State (summer rainfall area), with irrigated wheat production areas in the Northern Cape and central and western parts of the Free State.

A total of 51 fields were surveyed for RWA incidence: nine in the Swartland and five in the Rûens area of the Western Cape, three in the Northern Cape, six in the Western Free State, five in the central part of the Free State and 23 in the Eastern Free State. A total of 41 samples were collected from these fields, with 25,5% of the fields surveyed showing no RWA infestation.

Distribution of RWA

Environmental conditions, including temperature, humidity, rainfall, soil type and availability of host plants, play an important role in the population increase and distribution of different RWA biotypes. Because these variables change from year to year and between different areas, the distribution of RWA biotypes will vary over years and between different geographical areas.

In the 2020 season the new RWA biotype RWASA5 (recorded for the first time during 2018), was recorded on 13 wheat fields in the Lindley, Reitz, Daniëlsrus, Clarens, Ficksburg and Clocolan areas in the Eastern Free State (Figure 1). Populations of this biotype increased and have spread across the Eastern Free State since 2018 to become the most dominant biotype during 2020. The concentration of RWA biotypes occurred mainly in the Eastern Free State with no wheat fields infested with RWASA1 (original biotype, reported in 1978). RWASA1 still occurred mainly in the Western Free State and Northern Cape.

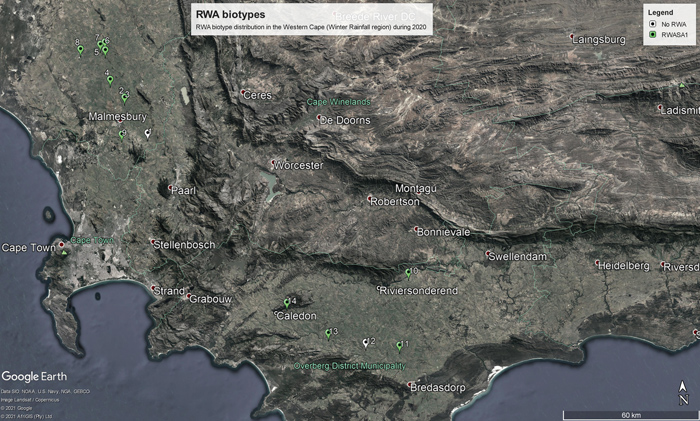

During 2020, RWASA1 was widespread in both the Swartland and Rûens areas of the Western Cape, with no other biotypes in these areas (Figure 2). The fact that RWASA1 was widespread in the Western Cape and that, in some cases, live populations were collected in fields recently sprayed with insecticides, may indicate insecticide resistance.

Conclusion

RWA, like other exotic aphid species, is capable of surviving at low population numbers for a relatively long period and can have sudden population outbreaks in new areas. Based on the recent RWA surveys, this insect pest is still present in all the wheat production areas of South Africa, despite management strategies such as deployment of RWA resistant cultivars and widespread use of insecticides. For this reason, it is important to continue monitoring the distribution of RWA and determining the occurrence of potential new biotypes and insecticide resistance in RWA populations in South African wheat production areas.

For further information please contact Dr Astrid Jankielsohn at JankielsohnA@arc.agric.za or 082 564 3795.