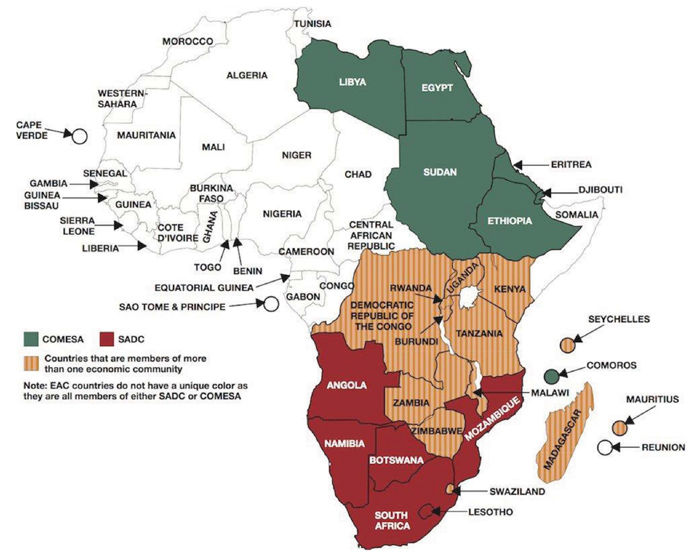

Three African regional economic communities (RECs) have taken a bold step towards advancing intra-Africa trade, consistent with the African Union’s action plan for boosting such trade.

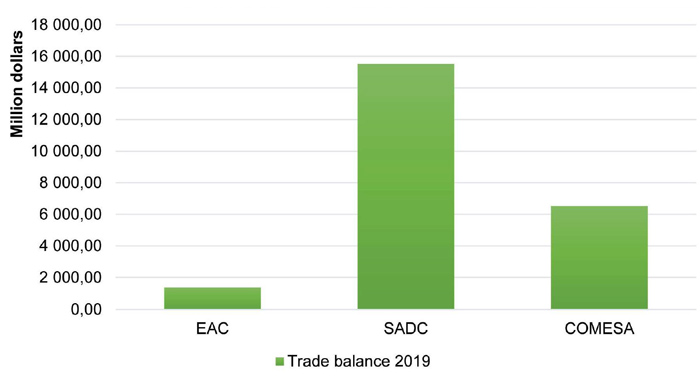

South Africa’s trade with the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the East African Community (EAC) and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) members was in excess of $30 billion in 2019, with the bulk of the trade within the SADC. South Africa’s trade with these regional communities represents about 16% of its trade with the world, with a positive trade balance for each of these RECs, indicating that South Africa’s exports exceed imports to these countries.

Before the advent of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) Agreement was launched in June 2015 in Egypt. The TFTA comprises of three regional economic blocks, COMESA, the EAC and the SADC. South Africa signed the agreement in July 2017 after conclusion of the negotiations for the legal text in May 2017; ratification took place in October of the same year. Out of the 26 member states, 23 have signed the TFTA Agreement. According to the parties involved, the agreement will enter into force once 14 member states have ratified it. Thus far, eight member states have ratified the agreement, namely Egypt, Uganda, Kenya, South Africa, Namibia, Rwanda, Burundi and Botswana. Seven countries are in advanced stages of the ratification process: the Comoros, Eswatini, Malawi, Sudan, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. For those that have deposited their instruments, it means that they have formally and legally committed to the TFTA.

This agreement focusses on three areas: market integration, industrial development and infrastructure development. These three pillars have been prioritised to support the regional economic integration efforts in the region and continent, with the aim to reduce obstacles that exist to trade in the RECs, deterring industrial production and movement of people, goods and services. The tripartite model advocates for a value chain approach to exploit and process commodities within the region instead of exporting primary goods. The tripartite model addresses not only the types of goods to be produced in the region, but also the technological requirements thereof.

Source: Trade Map

The agreement covers two phases: firstly negotiations of tariff liberalisation, rules of origin and trade remedies and secondly, liberalisation of trade in services and trade-related issues such as intellectual property rights, competition policy and the free movement of business people. The tripartite agreement was therefore a launch pad for the Continental Free Trade Agreement (CFTA). Covering half the African continent, the tripartite agreement meant that more than half the job of creating the CFTA was already done.

The general objectives of the TFTA will be to:

- Promote the rapid social and economic development of the region through job and wealth creation and the elimination of poverty, hunger and disease through building skills, innovativeness and hard and soft infrastructure.

- Create a large, single market with free movement of goods and services and business persons, and eventually to establish a customs union.

- Resolve the challenges of multiple membership and expedite the regional and continental integration processes.

- Build a strong people-based TFTA.

- Promote close cooperation in all sectors of economic and social activity among the tripartite member states.

The key features of the agreement

Recognition of differentials in levels of economic development

With the objective to create a single TFTA market, special and differential treatment provisions allow developing countries and least developed countries (LDCs) to determine when they will implement individual provisions of the agreement, and to identify provisions that they will only be able to implement upon the receipt of technical assistance and support for capacity building.

Variable geometry

Variable geometry regarding pace of liberalisation across negotiating regions is the second type of non-discrimination regarding FTAs. In practice the variable geometry translates into the fact that each act produced within the institutional structure in order to pursue the organisation’s aims, is submitted for consideration to the member states, who are free to accept it and then to incorporate it into the national legal system with a further approval given in accordance with domestic law. This principle will allow those who want to liberalise faster to go ahead.

Building on the existing ‘acquis’ of the RECs

The agreement provides that all previous commitments made under the RECs are built into the new TFTA Agreement as part of the ‘acquis’, or accumulated body of commitments associated with the TFTA. Member states will apply the REC ‘acquis’ to the other countries subject to reciprocity.

Potential benefits of the agreement

- Promotion of intra-regional investment and a boost to intra-regional trade.

- Some of the TFTA countries are among the fastest-growing economies in the continent, such as Rwanda, Ethiopia and Tanzania, giving South Africa access to new and dynamic markets. South Africa will build on its current share of the African market and have access to a larger, more integrated and growing regional market.

- This is an opportunity to stimulate industrial development, investment and job creation.

- Predictability and legal certainty of markets in the TFTA.

- Legal protection for South African exporters as the agreement makes provision for a dispute settlement mechanism that is dissociated with national courts.

Potential threats associated with the agreement

- Risk of transhipment where third-party exports gain preferential access to domestic markets through neighbouring countries.

- Risk of influx or dumping of substandard goods into the local market.

- Non-implementation of commitments by regional partners with implications for preferential access for South African exports.

- Risk of implementation of barriers to trade with implications on movement of goods across the region.

How do we mitigate the potential threats?

- Implementation of the development integration agenda and all its pillars (industrial and infrastructure development) to broaden the benefits to all the participating member states.

- Effective customs cooperation as transhipment will undermine regional productive capacity and benefits for all the participating countries.

- Effective border management and enforcement of agreed rules of origin to ensure that preferential access is granted to products that meet the rules.

- Good quality infrastructure, institutions and implementation of safeguard provisions.

- Capacity building and sharing of experiences and expertise among regional institutions to promote trade.

Connection between the TFTA and AfCFTA

There is a strong interface between the two agreements. It can be observed that the TFTA modalities are more ambitious than that of the AfCFTA, which provides for 100% product coverage with a tariff elimination period of five to eight years, but with 60% to 85% of tariff lines to be liberalised upon entry into force of the agreement.

The text of the TFTA instruments was used in negotiating the AfCFTA and the two sets of texts are similar – and in most cases identical – especially for the annexes. Therefore, there is a significant interface in terms of principles, texts, processes and architecture. The three TFTA RECs also form part of the eight RECs recognised by the AfCFTA as building blocks.

Potential implications on the grain markets

When trade agreements are negotiated, the natural question to ask is what will the implications be for different industries. The major concern for the grain sector is transhipment and dumping of commodities on the local market, where governments control the grain and oilseed stocks, which leads to unfair trade practices towards trade partners.

The TFTA Agreement has specific rules and procedures to cover anti-dumping. In addition, member states have anti-dumping rights under the World Trade Organisation (WTO). There is therefore legal protection under domestic and international law. The TFTA has provisions for infant and sensitive industry protection in the event that they are negatively affected by imports. Member states can therefore petition the protection if the need arises. Moreover, liberalisation is to be phased over a long period.

Conclusion

Even though the tripartite negotiations were launched prior to the CFTA, which entered into force on 1 January 2021, the TFTA is still relevant for the trading partners. Yet it seems like there is no longer political will to continue, which could be because of the fast pace of the AfCFTA or it could be the lack of resources to participate in parallel negotiations. If anything, not all is lost as the TFTA created a good starting point for the AfCFTA negotiations. There is no certainty on when the agreement will enter into force. However, Grain SA remains a part of the Agricultural Trade Forum (ATF) and members will be kept abreast on any changes related to the status of this agreement.