agricultural economist, Grain SA

Data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) shows that the African continent only conducts 15% of intra-regional trade, despite geographical proximity – compared to around 47% in America, 61% in Asia and 67% in Europe. In 2018, the total intra-African agricultural trade was valued at$25 billion ($13 billion in exports and $12 billion in imports) representing only 18% of the total intra-African exports and 16% of intra-African imports (Tralac, 2019). Data also shows that South Africa is the main exporter of agricultural commodities to the rest of the continent, followed by Uganda and Zimbabwe. The minimal intra-African trade has prompted the establishment of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA).

AfCFTA came into force on 30 May 2019 for the 24 countries that committed to the agreement. Article 23 of the agreement required a minimum of 22 ratified instruments (documents which must be signed by an appropriate official of the respective national governments) for the agreement to take effect. This was reached on 29 April 2019. Since then, six other countries have also deposited their instruments of ratification, bringing the number to 29, including South Africa. Out of the 55 African member states, Eritrea is the only country that has not signed the agreement. Those that have signed but not ratified, are not yet bound by the agreement – they agree in principle to the agreement, but still require national approval. Trading under the agreement will commence on 1 July 2020.

The design of the AfCFTA is in accordance with the multilateral rules applicable to a free trade agreement governed by the World Trade Organisation (WTO). The first phase of the agreement covers trade in goods and services, while phase two negotiations will cover competition policy and intellectual property rights. Disciplines incorporated from the trade regulating instruments of the WTO include remedies and standards.

Market increase

This regional integration is expected to generate significant gains. UNCTAD figures also show that once fully implemented, the gross domestic product (GDP) of most African countries could increase by 1% to 3% once all tariffs are eliminated. Intra-African trade will be boosted by 33%. According to the Minister of Trade and Industry, Ebrahim Patel, the AfCFTA is a potential game changer, as it can assist to lift the performance of the South African economy. Market integration will give Africa better bargaining power with bigger economies. This agreement will allow South Africa to remove boundaries and soften borders for easier movement of goods and later services and capital. The AfCFTA is meant to unlock West and North Africa for South Africa, creating new market opportunities. The Minister acknowledged that there are potential threats to the domestic market, which need to be identified and mitigated. Sensitive and strategic industries have been highlighted and attention will be given to mitigate risk and boost capabilities.

Modalities of the AfCFTA

The AfCFTA modalities entail a progressive reduction and elimination of customs duties and non-tariff barriers on goods. The goal is to reduce 90% of tariff lines to zero immediately from the date that trade takes effect. The modalities also provide for members to negotiate on sensitive products, on a request and offer basis, on which tariffs would reduce to zero over a longer period – thirteen years for Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and ten years for others. The sensitive products and their schedules of tariff reductions may be different in each bilateral relationship. The remaining 3% is set aside for industries that governments deem too delicate to open up to trade. These form part of the exclusion list and there are no reductions for tariffs on this list. The exclusion list is subject to an anti-concentration clause, to ensure that members are not able to include entire sectors in their exclusion lists.

Trade within regional economic communities (RECs) will continue according to the trading regimes they have in place (customs unions or free trade areas). New tariff reduction under AfCFTA will only occur among member states that do not have an existing agreement with one another. For example, Southern African Customs Union (SACU) member states do not have any existing preferential trade arrangements with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), so tariff concessions need to be determined.

Rules of origin

The objective of rules of origin is to prevent trans-shipment, where goods from a non-preferential country are imported into a preferential trading area at preferential rates of duty. Within Africa various RECs have different approaches to rules of origin. For instance, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) has a general rule of 35% value addition, while the Southern African Development Community (SADC) has product-specific rules of origin. These REC rules of origin will stay in place for these trading areas. It is expected that the AfCFTA will take a mixed approach, with both a general rule and product-specific rules in sensitive categories. A committee on rules of origin will be set up under the AfCFTA agreement to review progress annually.

Potential threats associated with the AfCFTA for South Africa

AfCFTA will not come naturally and without problems. Trade agreements produce potential gains and losses in production, exports and employment. Those positioned to expand their exports can gain.

South Africa has identified the following issues as challenges:

- Import-competing sectors may face increased competitive pressures that can result in job losses and losses of industrial capacity.

- Risk of trans-shipment where third party exports gain preferential access to domestic markets.

- Risk of influx of substandard goods into the local market.

- Intra-African trade is dominated by primary goods, meaning we would still rely on other regions for processed/finished goods.

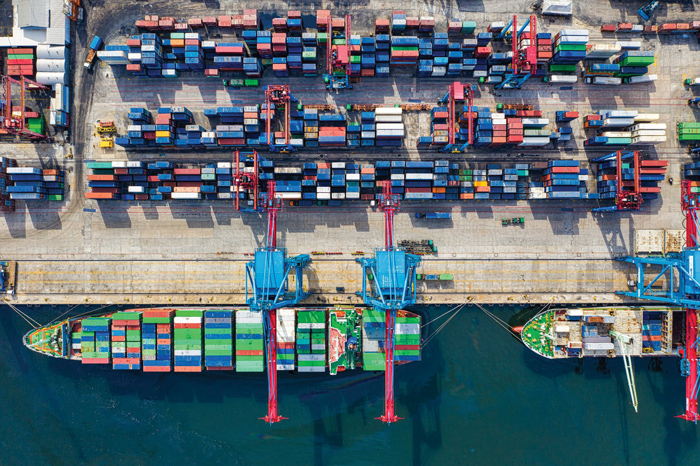

- Relatively higher trade costs in comparison to other markets like Asia and the European Union due to the quality of road and port infrastructure.

- Port/border procedures and other social risks (social unrest, theft, corruption).

- Non-implementation of commitments by regional partners with implications for preferential access for South African exports.

- Food safety within the agreement.

- Most African countries do not have the required domestic arrangements to undertake trade remedy investigations.

How should these potential threats be mitigated?

Strategies

- Effective customs capacity to monitor and implement the rules of origin to prevent trans-shipment.

- The South African Revenue Service (SARS) needs to identify weaknesses, threats and strategies to improve customs enforcement capacity.

- Effective implementation of national product standards.

- The dispute settlement mechanism should be effective and disputes should be treated as non-political matters.

- Effective implementation of trade facilitation programmes to reduce the cost of trade.

- Capacity building and sharing experiences and expertise with other member states.

- Investment in logistic infrastructure through cross-border institutions like the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC).

Trade remedies

Trade remedies are trade policy tools used by governments to take corrective action against imports, which cause injury to domestic industries. Trade remedies consist of anti-dumping, countervailing and safeguard mechanisms. The AfCFTA makes provision for all three trade remedies. It should be noted that trade remedies do not currently feature in intra-African trade, because most governments do not have the required domestic arrangements to undertake trade remedy investigations. The above-mentioned remedies can be defined as follows:

- Anti-dumping mechanisms: Provide protection to domestic industries against dumped imports. This includes the selling of products below the normal value.

- Countervailing mechanisms: The use of a subsidy by a member state towards its industries can be remedied either through the dispute settlement mechanism where the subsidy should be removed or the adverse effects thereof or through countervailing measures, where an extra duty is imposed on subsidised imports to offset the injury to domestic products.

- Safeguard mechanisms: This is an action taken by a member state when there is a surge of imports that threatens or causes serious injury to domestic industries. This may include restrictions of imports for the particular product temporarily to help the domestic industry to adjust.

Although trade remedies are part of the AfCFTA, the biggest problem on the subject of domestic industry protection against unfair trade practices and import surges, is that domestic investigating authorities are not available in most countries. So far, South Africa and Egypt are the only two members that actively use trade remedies. However, domestic institutions like the International Trade Administration Commission (ITAC) can take on regional as well as global investigations.

Conclusion

Throughout this whole process, Grain SA has been working closely with government through the Agricultural Trade Forum (ATF) to sensitise them to grain industry issues and to make sure that the industry is protected in terms of liberalisation, rules of origin and the overall implementation of the agreement. The AfCFTA comes with potential challenges and risks, particularly at the implementation phase. If governments have the political will and set the right systems in place to govern against risks and challenges for local industries, this agreement should be successful and a force to be reckoned with among trade blocks.