In this article we will explore the main elements of the new agricultural remedy labels – important information for producers and farmworkers to take note of. But first, why did these labels change to begin with?

The Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals, developed by the United Nations and commonly referred to as the ‘GHS’, is an internationally harmonised approach to classifying and labelling of chemicals that conveys the hazards associated with a chemical in a standardised way. The need for GHS arose because of the global trade of chemicals, which often cross boundaries into areas with different languages and varying levels of literacy, thereby creating challenges when communicating safe and responsible usage instructions of the products. The most noticeable changes brought about by GHS is the way in which the chemical is classified and how this information is conveyed to the user, resulting in changes to the labels and safety data sheets (SDSs) of chemicals. It is important to note that even though the label and SDS of a chemical have changed, the hazards associated with the product did not change, only the way in which these hazards are communicated. This article will look at the main changes in the product label, and not necessarily all the changes in the SDS, although they may be referenced for context.

In South Africa, GHS became a legal requirement for all hazardous chemicals from September 2022 with the promulgation of the Regulations for Hazardous Chemical Agents No. R280 under the Occupational Health and Safety Act (Act No. 85 of 1993) on 29 March 2021. An extension for implementation for agricultural remedies was later provided to 30 September 2023, with these changes still being phased in. The requirement for GHS for agricultural remedies specifically, is also included in the Regulations relating to Agricultural Remedies promulgated on 25 August 2023 under the Fertilizer, Farm Feeds, Agricultural Remedies and Stock Remedies Act (Act No. 36 of 1947).

How does it work?

It is important for producers, farmworkers and anyone handling a chemical to understand how GHS works, because the hazards associated with a particular chemical, their nature and severity, are communicated through a number of elements, such as hazard statements, pictograms and signal words on both the label and the SDS of the product. It is only when we understand the hazards associated with a chemical that we can effectively mitigate the risks.

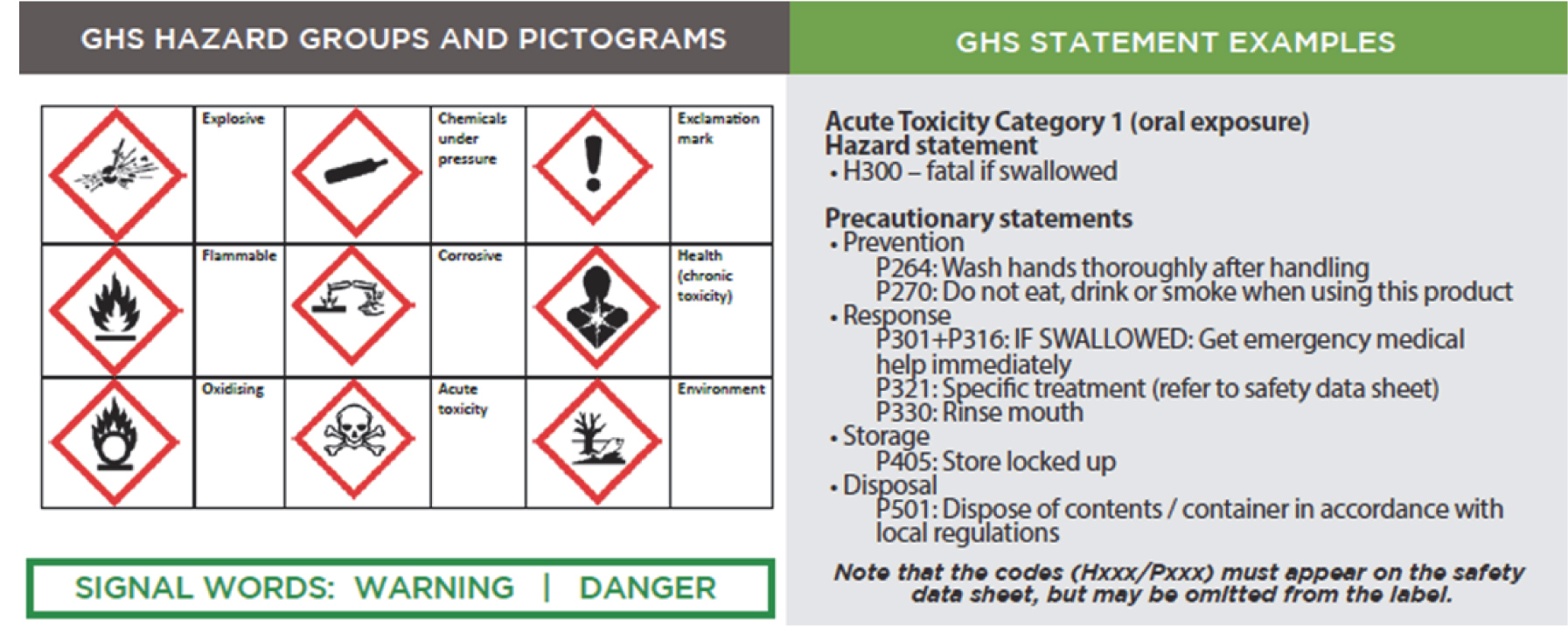

First, let’s have a look at the classification criteria of these hazards. According to the GHS, the nature of a hazard is assigned according to a hazard class, of which there are currently 29. Of these, 17 are physical hazard classes such as oxidising liquids, ten are health hazard classes such as skin corrosion/irritation, and two are environmental hazard classes, namely hazardous to the aquatic environment or hazardous to the ozone layer. Not all of these hazard classes will be commonly associated with agricultural remedies, however.

Within these classes, the severity of the hazard is then allocated in terms of a hazard category expressed as a number, for instance category 1 would be the most severe. Category 2 would be less severe than category 1, but more severe than category 3, and so forth. Some of these categories are further sub-divided into divisions, which are expressed as a letter (i.e. A, B, C).

The GHS also uses hazard statements, pictograms and signal words to communicate the hazard of the chemical, as well as precautionary statements to mitigate any potential risks. These are all linked to the hazards that have been identified.

Hazard statements

Hazard statements are phrases that describe the hazard/s as determined by the hazard classification. They start with the letter H followed by three numbers. For physical hazards, the statement will start with H2 (followed by two additional numbers), health hazards start with H3 and environmental hazards with H4, for example, H300: Fatal if swallowed. These hazard statements appear both on the label as well as the SDS; however, the code (i.e. Hxxx) only needs to appear on the SDS and not on the label.

Precautionary statements

Precautionary statements are linked to the hazard statements and are used to explain how to handle these substances, as well as which precautions to take to ensure any risk associated with handling the product is mitigated. The precautionary statements are preceded by the letter P and three numbers that are also categorised according to type, similar to the hazard statements. For instance, general statements will start with P1 followed by two numbers, prevention statements with P2, response statements with P3, storage statements with P4 and disposal statements with P5, for example, P264: Wash hands thoroughly after handling. These statements appear on the product label and the SDS. As with the hazard statements, the codes (i.e. Pxxx) are only required on the SDS and not the label.

Signal word

Based on the hazards identified and the corresponding categories and thus the severity thereof, a signal word is used to describe the hazard. The signal word ‘Danger’ is used to describe more severe hazards, and the signal word ‘Warning’ is used to describe less severe hazards. A chemical will only include one signal word which will be the most severe signal word flagged during the hazard classification.

Pictograms

A pictogram is a graphical representation of the hazards associated with the chemical and is associated with a specific hazard class and category. All pictograms prescribed by the GHS have a black symbol on a white background with a red frame. With the exception of the exclamation mark, all pictograms flagged by the hazard classification must always be included on the label and SDS of the chemical.

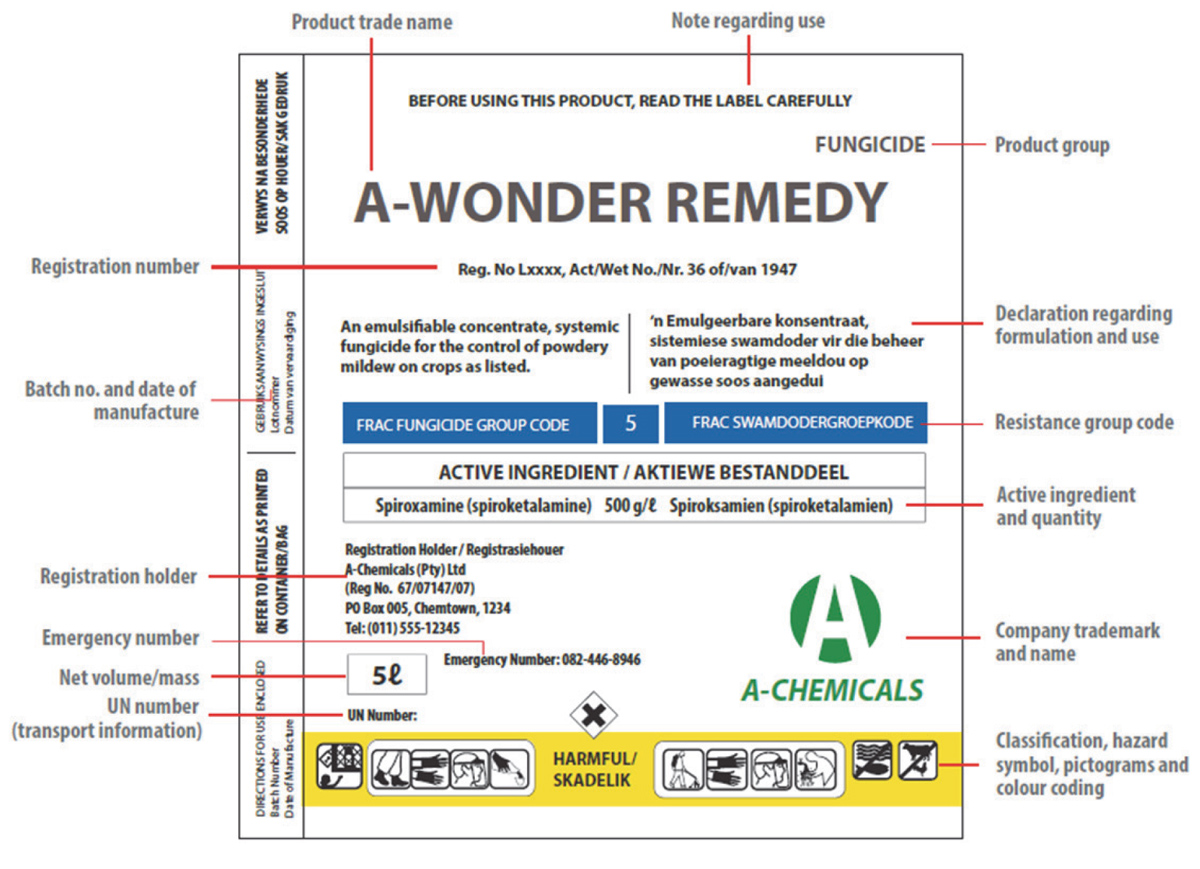

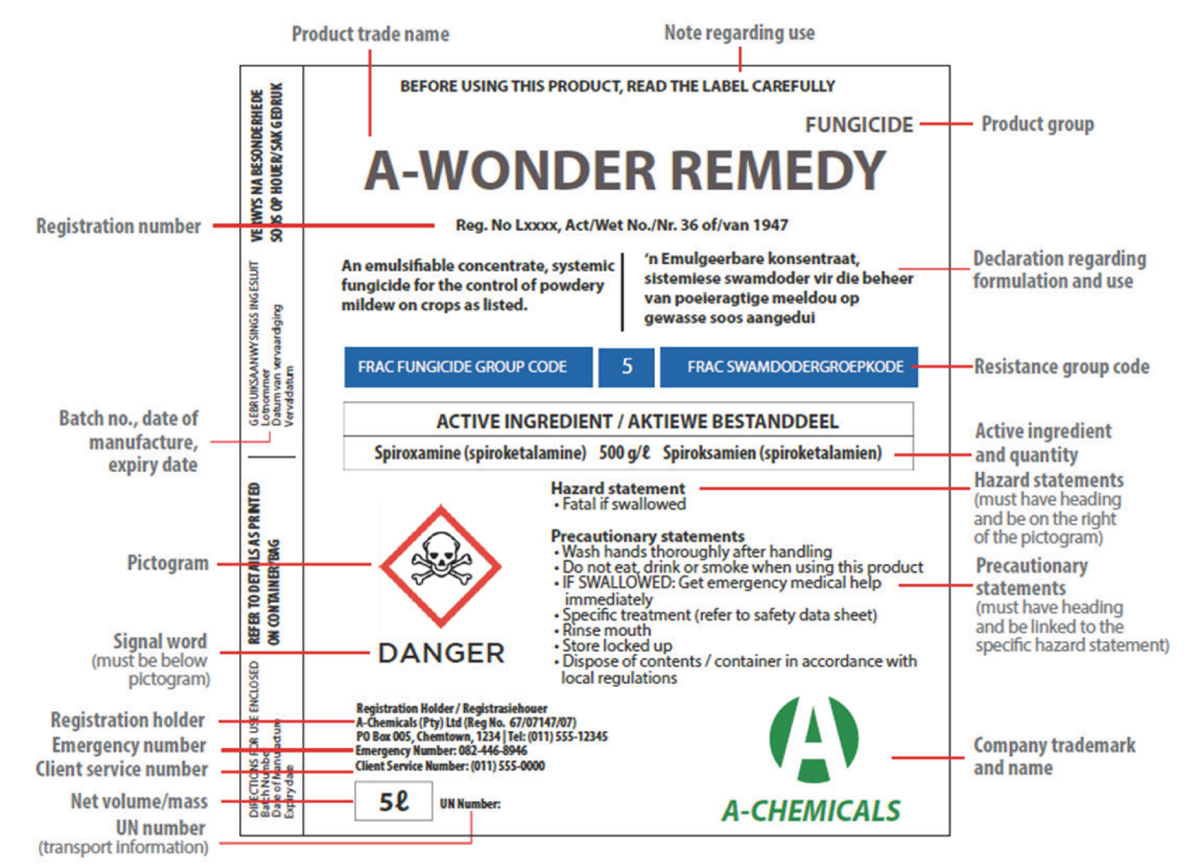

What changed on the label?

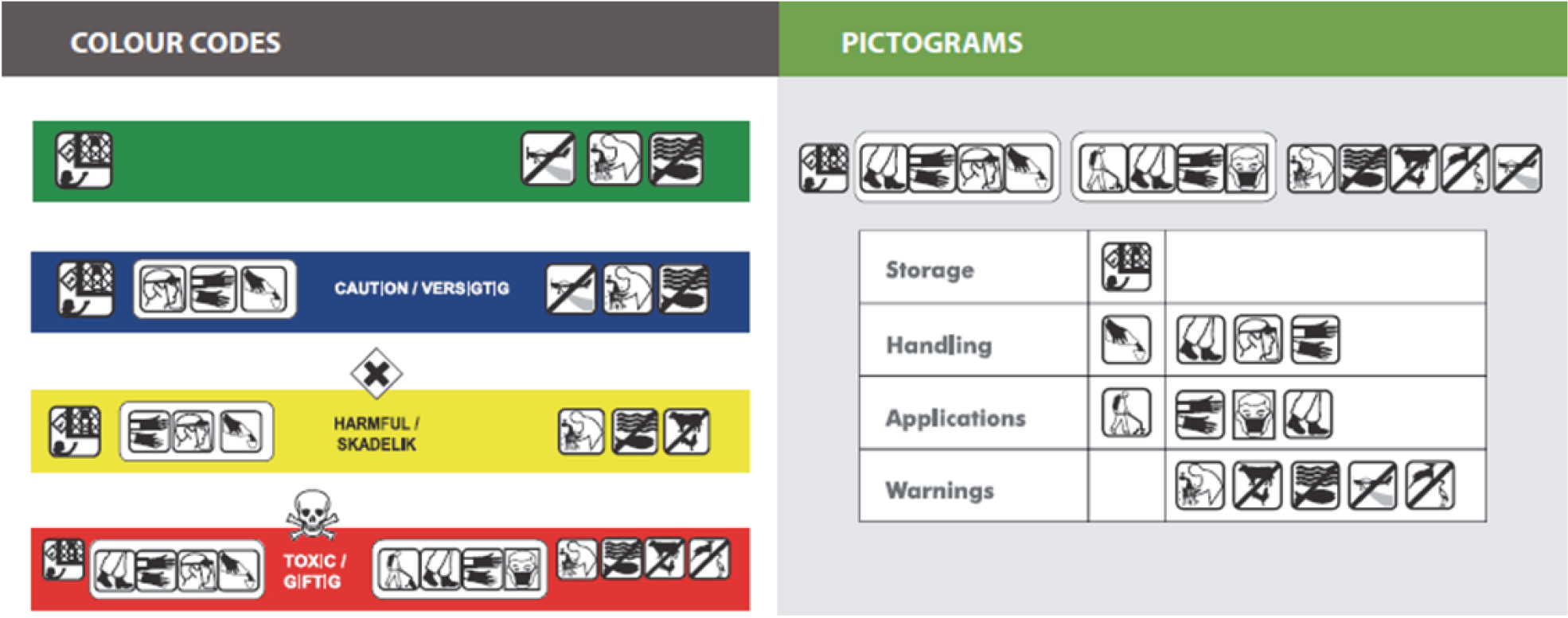

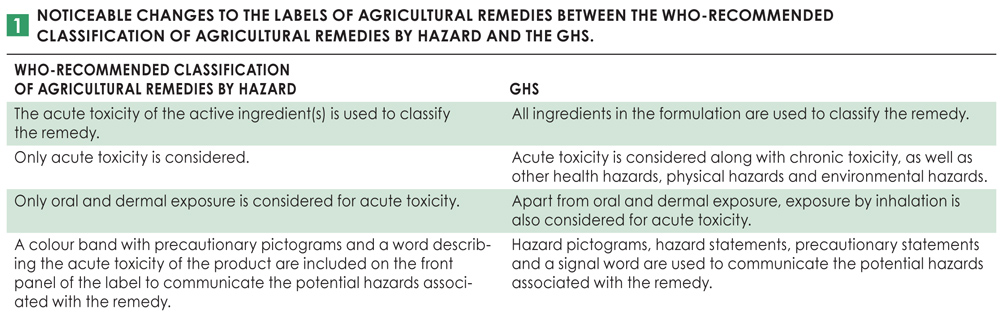

In the past, agricultural remedies were classified and labelled according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommended classification of pesticides by hazard. This system classified the remedy based on the acute oral and dermal toxicity of the active ingredient(s), which was reflected in the colour band at the bottom of the front panel of the label. Pictograms on the colour band provided information on the personal protective equipment required and general precautions to take when storing, handling, or applying the remedy. A corresponding word based on the severity of the toxicity was included on the colour band (Caution, Harmful or Toxic).

With the implementation of the GHS, the most noticeable change to the label of an agricultural remedy is the removal of the colour band and corresponding pictograms, and the inclusion of the GHS hazard pictograms, hazard statements and precautionary statements. The GHS covers more hazards than the previous WHO system and classifies the remedy based on physical, health and environmental hazards, not just acute toxicity. It also considers the active ingredient(s) as well as the inert ingredients in the formulation. Consequently, the GHS is a lot more comprehensive in terms of hazard classification and communication than the WHO system.

As mentioned, it is important to note that even though the label and SDS of a chemical have changed, the hazards associated with the product did not change, only the way in which these hazards are communicated.

Hazard versus risk

The degree of a chemical’s capacity to harm depends on its intrinsic properties, i.e. its capacity to interfere with normal biological processes, and its capacity to burn, explode, corrode, etc. The concept of risk or the likelihood of harm occurring, and subsequently communication of that information, is introduced when exposure is considered in conjunction with the data regarding potential hazards. The basic approach to risk assessment is characterised by the simple formula:

hazard x exposure = risk

Thus, if you can minimise either hazard or exposure, you minimise the risk or likelihood of harm occurring.

The GHS’s aim is to communicate the inherent hazards of the chemical. Because of these hazards, there are certain risks involved with working with the product, but these are mitigated if the label instructions are followed. Just because a product is hazardous does not mean it cannot be applied safely. A vehicle, for instance, can also be a hazard if you consider the number of accidents on the road, but we don’t just ban vehicles altogether because of this. Instead, we mitigate the risk by wearing a safety belt, adhering to the speed limit and following other road safety regulations. The same logic applies when working with hazardous chemicals, which is why understanding the product label and safety data sheet is so important. And remember, any application of an agricultural remedy in any manner other than the label instructions is a contravention of the law. So do the right thing and make sure you, and any person working with you, know exactly how to use these products safely and responsibly.