During the last summer production season of 2022/2023, Argentina suffered the worst drought since 1952. This article will explain the magnitude of the reduction of rainfall and its implications followed by a description of the different management tools that producers applied to try and mitigate the impact of this drought.

La Niña weather pattern

During the last three years, the country experienced a La Niña weather pattern that produces under average rains in Argentina and parts of South America and above average rains in South Africa. Brazil, as an exemption this year, had a season with rains above the average, leading them to a record crop that helped to compensate for the shortage of an Argentinian crop in the international market.

Argentina had to face the occurrence of several heat waves during the summer of 2022/2023. There were eight heat waves with the worst taking place from 27 February till 20 March with temperatures that peaked up to 40 °C in the north and central part of Buenos Aires, Santa Fe and Córdoba – the main soybean production areas.

Photo: Javier, Flickr

Another major consequence worth mentioning was the severity and strength of the storms and rains that were received. The shifts in temperature that happened when these warm masses of air met with cold fronts coming from the Atlantic Ocean ended in heavy storms with hail and strong winds. So, on top of having scarce storms, a lot of water was lost to run-off and poor penetration in the soil that was compacted because of the drought.

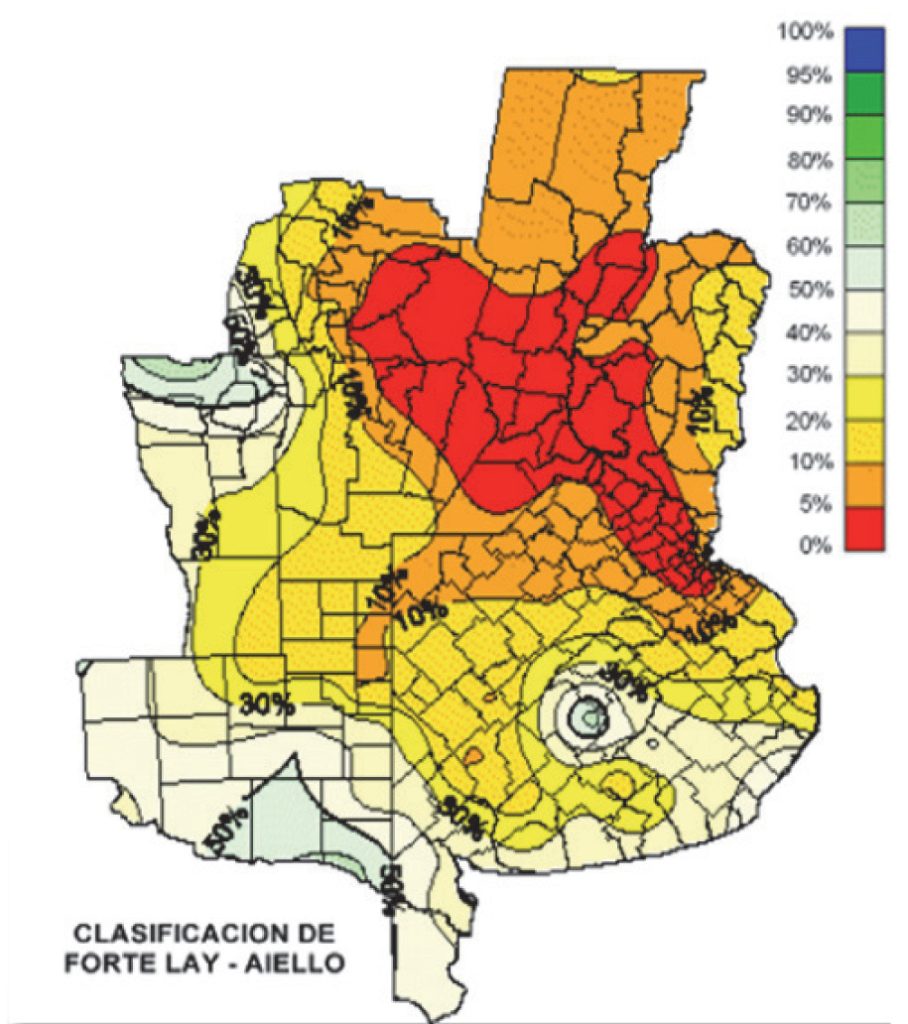

Figure 1 shows the water available in the soil on 10 January in the middle of the third heat wave, compared to the 30-year average on the same day. At this time the crop of soybeans was at the most demanding period for water and nutrients. The figure shows that the main areas had only 10% to 20% available water when compared to the last 30 years. Despite this situation, Argentina managed to get to 50% of a normal crop production year.

Source: Rosario Board of Trade webpage. Historical Relative Humidity Maps for January 10, 2023. https://www.bcr.com.ar/es/mercados/gea/clima/clima-gea/humedad-relativa.

As said before, La Niña has been in effect over the last three years, but the worst was in 2023. This situation gave producers time to prepare and find ways to be more efficient in their farming practices to try and get out a higher output from the few millimetres of rain received.

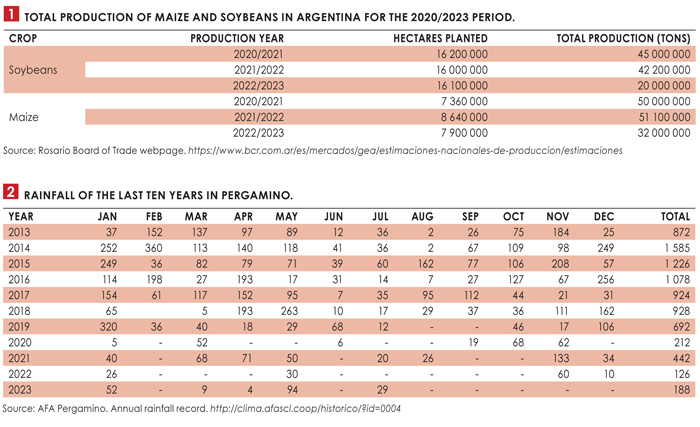

Table 2 shows the rainfall of the last ten years in Pergamino, the capital of the maize belt of Argentina and home of the best soils in the country. The table indicates that from 2019 onwards, the rainfall amount was drastically shrinking from the 1 000 mm average that this area receives every year.

The 2019/2020 and 2020/2021 seasons were good production years despite the lower rainfall. This was due to the normal rains of the spring/summer and the presence of a full water table as a consequence of previous years with above average rains.

The 2019/2020 and 2020/2021 seasons were good production years despite the lower rainfall. This was due to the normal rains of the spring/summer and the presence of a full water table as a consequence of previous years with above average rains.

However, the situation started deteriorating during the winter of 2022 with very poor rainfall. The period between December and February in the 2022/2023 summer season was catastrophic for the crops, with many of them that were lost completely.

Production fields in Argentina

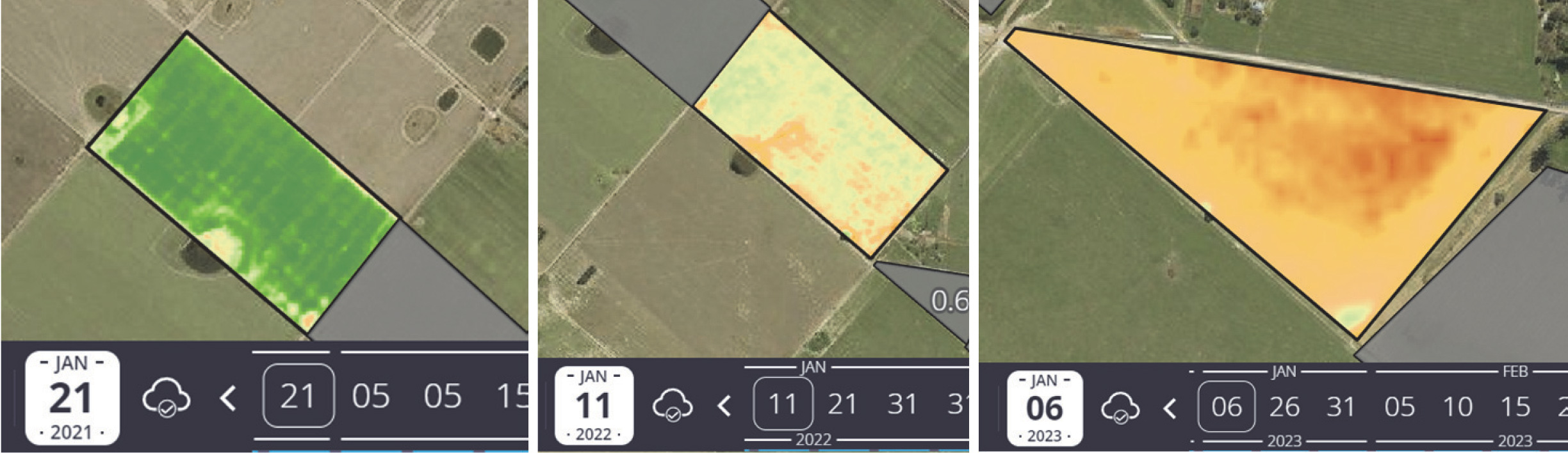

Figure 2 shows the NDVI images of Southern Hemisphere Seeds Argentina’s production farm in San Justo in the Santa Fe province. These fields are all contiguous; they share the same chemical and physical soil characteristics and were planted with soybeans for seed production in the last three seasons. The planting date, density and technology were the same for the three years and the cultivar used was Y 657.

Source: Southern Hemisphere Seeds internal management information (unpublished).

The fields were always planted between 10 and 17 November with maize as the previous crop. A very clear decline in production performance can be seen for the period. The crop at this stage was in R3 (pod setting).

Yield per year per hectare at SHS farm in San Justo:

- 2021: 4,5 tons (average national yield: 2,77 t/ha)

- 2022: 3,5 tons (average national yield: 2,64 t/ha)

- 2023: 1,8 tons (average national yield: 1,24 t/ha)

It can be seen how the yield came down from a normal production year in 2021 to a crop that yielded 1 ton less in 2022 to end in 2023 with a yield of 1,8 t/ha.

While in 2021 and in 2022 the grain and seed quality were standard, 2023 ended up with a very poor yield, with only 30% of seed viable and 70% not viable to be sold.

Photo: Ricardo Ceppi/Getty Images

Strategies used by producers during dry years

Producers started changing their management decisions in the last two seasons with good results and when they had to face the 2022/2023 season, there were already many lessons learned.

Although producers knew that they were facing a below average rainfall year in 2023, there was a clear indication by meteorologists that La Niña was going to start declining somewhere between late spring and mid-summer of 2022/2023. This forecast was delayed a couple of times and good rains were only received from May onwards. This was already too late.

Producers planned their crops with the following approach to make sure they got the best out of each millimetre of rain received:

-

-

- Available water in the soil: Producers took proper measurements on the water available in the soil as a go/no go criteria for deciding the planting of each and every field. Fields that had less than 50% of available water compared to normal years were not planted. Those fields with 50% to 70% of normal available water, were planted with less demanding crops. Finally, the fields that were closer to full capacity, or had irrigation, were planted with full specs using top performing cultivars/hybrids and full fertiliser packages. Sometimes, even with irrigation, the fields couldn’t cope with the evapotranspiration rate (9 mm/day) that occurred during the heatwaves. These crops suffered severe stress also.

- Planting dates: Because of having almost no rain during September and October, and having a prediction that La Niña was going to end mid-summer, most producers started planting later in the season. November and December were the months where most of the maize and soybeans were planted. These planting dates set the crop for a lower yield, but also a less demanding one in water. By delaying the critical periods into February, there was hope of having better chances and this strategy paid off.

- Crop rotation: In those fields where the available water was lower than 70% at planting, producers chose to plant soybeans against maize due to three main factors:

-

-

-

- Water consumption: Soybeans consume less water per ton produced than maize.

- Risk/cost: The input cost of soybeans is less than 50% of the input cost of maize. To reduce the risk, producers chose to plant more soybeans. There are no insurance policies offered to cover for drought in Argentina – there is no market for such a product.

- Planting flexibility: Soybeans give producers a wider planting span than maize. A lot of producers received random thunderstorms that allowed them to plant when it happened. Table 1 shows that the hectares of soybeans planted haven’t changed in the last three years, but the maize hectares were reduced by 10% in the 2022/2023 season.

- Fertiliser application: Producers applied a different strategy where they fertilised the fields with small applications and more frequently as the crop evolved. This allowed them to commit only what was needed for the next stage. This strategy was good to control the growth to the possibilities of the environment that the crop was in. Potential yield was calculated constantly, and producers made applications according to those expectations.

- Canopy and soil shadowing: Soybean producers chose to plant the soybeans in narrower rows to generate a quick canopy to try and reduce the evaporation to its minimum and cool down the soil maintaining the same plant population. This was very helpful together with the fields that had good no-till coverage. Big differences were seen between fields that worked with strategies of evaporation control versus the ones that were barren soil.

- Disease management: Producers had to work hard on keeping fungal diseases and insects under control. Having fewer good fields caused an unprecedent pressure of insect attacks and fungal diseases. This created the need for having to spray often to protect the little yield that they had.

Conclusion

Hopefully such a situation will never occur again. For the first time in many years, Argentina saw a total failure of crops in many fields scattered around every producing area.Despite this situation, the country ended up having half a crop with 20% of the water that they usually receive. Producers were able to find a way – as mentioned earlier – to maximise the use of water and avoid excess water losses due to evaporation.

The new El Niño weather pattern is still starting to settle and it’s not clear how it will affect the 2023/2024 season. At present, Argentina has a very good wheat crop growing and producers are looking forward to having another chance with the summer crops that can take them back to a normal production year.

-

-

-