As far back as 2009, government announced its plan to accelerate the rollout of economic infrastructure central to economic growth and development, industrialisation and competitiveness. This was to support the country’s medium- and long-term economic, social and environmental goals that formed part of the National Development Plan (NDP).

In formulating its vision for the energy sector, the NDP took as its departure the Integrated Resource Plan for Electricity (IRP 2010) for 2010 to 2030 as promulgated in March 2011. This has subsequently been updated as IRP 2019 in October 2019 as the official electricity plan up to 2030. The plan identifies 39 696 MW to be added to the national grid between 2019 and 2030. This included the 8 208 MW (20,7%) that have already been committed or contracted under IRP 2010, leaving 31 488 MW (79,3%) of new additional capacity that has to be added between 2019 and 2030.

To place this in perspective: Eskom currently has approximately 57 000 MW of generation capacity available. This is made up by hydro (3 485 MW), thermal (48 380 MW), wind (2 323 MW), solar (2 323 MW), and other sources (580 MW). More than 80% is made up of coal – with 24 100 MW of coal generation capacity set to be decommissioned in the next 10 to 30 years. According to Eskom, planned outages in September 2022 were at 5 411 MW, while breakdowns amounted to 16 326 MW.

To give effect to the procurement process and implementation of the relevant capacity allocations of the IRP, the Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy (in consultation with the National Energy Regulator of South Africa – NERSA) determines new electrical energy generation capacity requirements, as allowed by Section 34 of the Electricity Regulation Act (Act No. 4 of 2006). The determinations further specify whether the new generation capacity shall be established by Eskom, another organ of state or an independent power producer (IPP).

To give effect to the procurement process and implementation of the relevant capacity allocations of the IRP, the Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy (in consultation with the National Energy Regulator of South Africa – NERSA) determines new electrical energy generation capacity requirements, as allowed by Section 34 of the Electricity Regulation Act (Act No. 4 of 2006). The determinations further specify whether the new generation capacity shall be established by Eskom, another organ of state or an independent power producer (IPP).

Prior to the release of the promulgated IRP 2019, the procurement of electrical energy from IPPs was informed by ministerial determinations made in alignment with the IRP 2010. However, the electrical capacity that has not already been contracted before the promulgation of the IRP 2019, has expired. New ministerial determinations, with the concurrence of NERSA, will give effect to the capacity allocations stipulated in the IRP 2019.

In that regard, two ministerial determinations have been promulgated, following concurrence by NERSA. A total of 13 813 MW has been determined, which represents 43,9% of the total 31 488 MW target for new additional capacity that must be added by 2030 as stipulated in the IRP 2019.

The first determination, promulgated on 14 May 2020, calls for the procurement of 2 000 MW from a range of technologies to fill the short-term capacity gap.

A determination, which was promulgated in September 2022, allows for procurement from technologies for the short and medium term (Figure 2).

Fast forward to 2022: Window 6 closed on 6 October 2022 under the request for proposals (RFP) of the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producers Procurement Programme (REIPPPP). This window has been increased to 4 200 MW made up of 3 200 MW wind energy and 1 000 MW solar photovoltaic energy resources.

Generally, wind towers erected in South Africa are in the range of 3,5 MW. Therefore, in terms of towers, this means the 3 200 MW to be added represent approximately 920 towers.

Where are these towers to be erected?

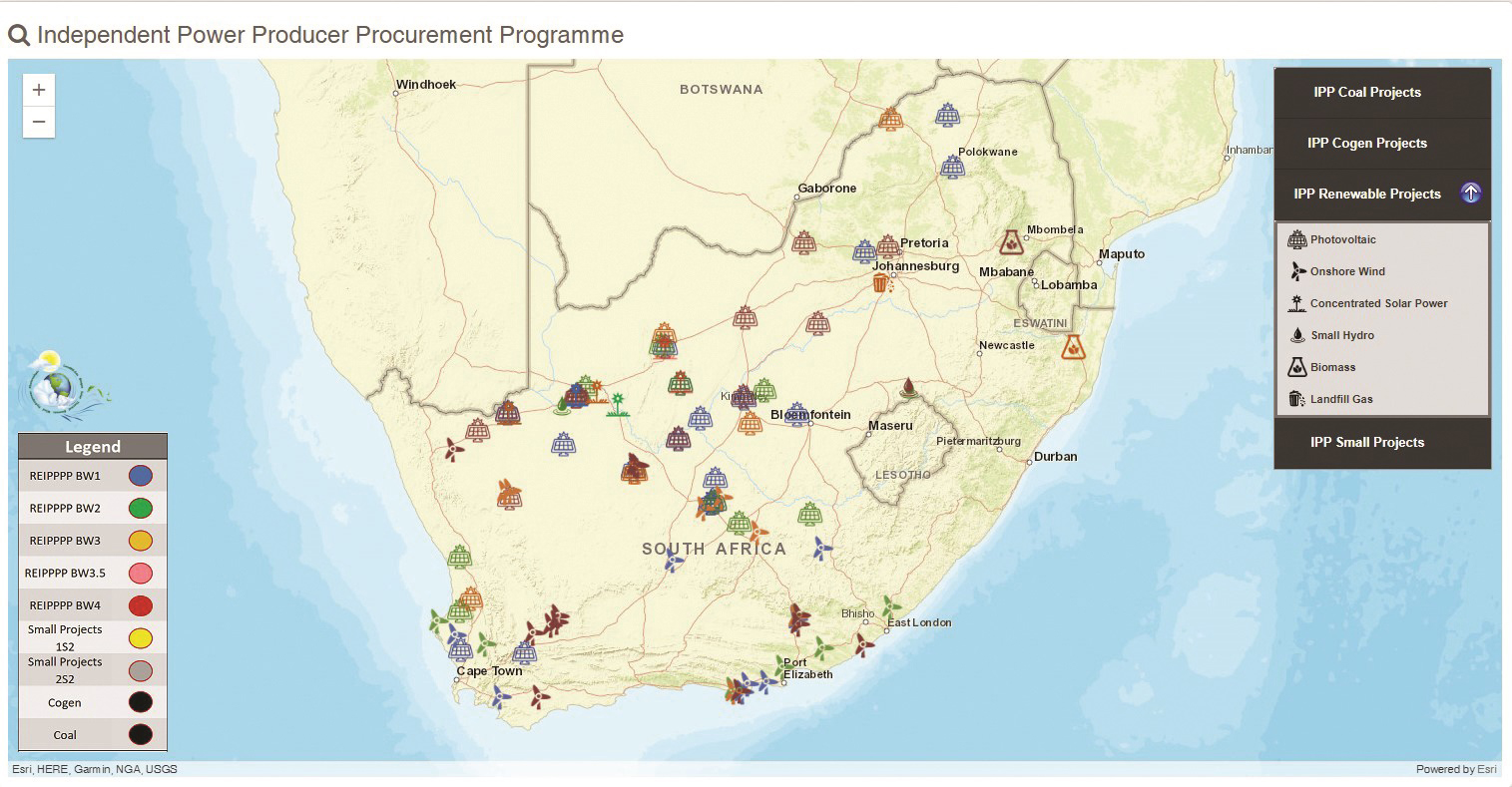

It would appear from Figure 1 that wind projects are situated around the Western and Eastern Cape coastal belts and through the Karoo, with solar projects being favourable in the western areas of the Western and Northern Cape. The preference is certainly also influenced by the location in relation to access to the national grid network as power generated needs to be fed into this network. Building and expanding this network in order to connect to the grid can dramatically affect costs and derail the feasibility. The golden rule is to be close to the overhead grid lines. A substation will also have to be built to feed into the grid.

These projects are spread across productive commercial farms. We will now try to lay out some of the general aspects that need to be considered and some of the possible pitfalls when getting involved with these types of projects.

How does the process work?

Generally producers will be approached by a ‘scout’ or ‘contracting agent’ that will want a lease option agreement to be signed. These option contracts are normally basic in nature and generally for a period of five years with an option to extend for five years. They normally try to include a confidentiality clause in these contracts. The advice is to have this clause removed. In many cases, your neighbours will also have been approached. It is at this point that you need to consider forming a grouping to ensure that as a collective you are in the best possible position to negotiate. This will also help you as a grouping to consider various factors that might affect you and be particular to your area.

These scouts then on-sells this option contract to the developers. This contract gives him the right to a percentage-based income from the project over the duration of the project’s lifetime should the project be finalised and commissioned. Some developers have moved away from this system as margins have come under pressure. Initial contracted rates for the first approved projects were almost double that of the generation cost of Eskom’s thermal units, but the bid process now sees prices lower than Eskom’s current generation cost being tendered for, resulting in lower margins. While the technology has dramatically reduced in price, margins remain relatively tight on renewables. This lease option and the property are then subject to a feasibility study where masts are erected that measure wind capacity or devices placed on site to measure the solar radiation potential.

If data are available for the area, the monitoring and data collection period can be reduced. However, it can take a period of two years for environmental impact assessment (EIA) studies to be conducted and concluded.

Signing the contract

Signing the contract

Once the feasibility studies have been completed and during the EIA process, the landowner will be approached to conclude a more detailed contract in the form of an addendum.

This is where the snags and complexities of contracting, and the rights of landowners need to be considered if not done in the initial contract, which is preferrable. The best is to tackle some of the issues that will be mentioned in that initial option to lease contract – it will help going forward. It is important that ‘common sense’ is used when signing any contract, bearing in mind that this could eventually be for a period of more than 25 years.

Initially no remuneration is offered in the option to lease contract. This contract must, however, take into consideration the producer’s ability to continue production and farming without impediments. The tenant’s activities and income must be limited to the generation and sale of electricity, while as landowner you can still get involved in agro tourism and other activities on your property, provided that those activities do not prevent or impede the tenant’s ability to generate and sell electricity. The EIA and monitoring must be conducted in a way that also do not place restrictions on your activities.

The first and most important aspect to consider is access to your property and security. One of the biggest advantages in agriculture is where you can ‘lock your gates’. Access needs to always be controlled and penalties considered where this is not done, or unauthorised people allowed access (individuals seeking work or livestock as example). Registers also need to be kept of all persons entering your farm. As landowner your own movements must not be restricted on the property.

Accommodation at any stage, given the determinations of ESTA legislation, should not be considered. Specific restrictions of no housing or accommodation on site should be addressed. Alternatively careful and detailed prescriptions in the contract should be in place.

The area to be leased must be clearly defined. Not merely the whole title deed, but rather a detailed area on the title deed. There should be two dates detailed in the contract: the commencement date and the commissioning date. The commencement date refers to the start of construction and the commissioning date to the power generation supply date. Rental should be paid as soon as construction starts. This could be less than the contracted amount once the project is commissioned, but the principle should be considered.

Rates of rental will differ for these two periods. The first should be an agreed upon amount and the second for the period after commissioning the greater of a percentage based on the gross electricity sales of at least 2% or a guaranteed amount of at least 75% of this potential as determined by the feasibility studies. The landowner has no control over contracting and sale of electricity or maintenance, hence the guaranteed amount. Intermediaries could also form part of the contract as projects are sometimes sold by developers over time to investment companies, hence rental determined on gross electricity sales. This gross income needs to be properly defined. Consumer price index- (CPI-)based increases to rental amounts need to be implemented from the signing of the contracts on an annual basis and not from commencement or commission dates. There can be a long period before commencement or commissioning after the initial signing of the contracts.

Municipal land tax is determined by the value of the land plus the infrastructure that is present on the land. While the validity of rates and taxes on agricultural land is not under discussion here, the principle of who should pay for the taxes on the increased structural value because of the project needs to be considered. This additional cost and any other relevant levies or taxes should be defined and payable by the developer and/or project owner. This can run into millions of rands over the lifetime of the project.

Servitudes will be registered over access roads and parts of the property. The road infrastructure as well as footprint can and will be extensive and owners must protect the right to sign off on the final project layout. Utilising low potential land as opposed to high potential land makes sense. Maintenance of this infrastructure, such as fences and roads, needs to be detailed in the contract. The removal of these servitudes and the associated costs need to be considered on completion and decommissioning of the project.

The removal of infrastructure and the rehabilitation of affected areas need to be addressed as well. Landowners must be in a position to acquire this infrastructure at a negotiated price on decommissioning or request that some of the infrastructure is left in place such as roads and fences. This must be negotiated on decommissioning. Runoff water as a result of the infrastructure erected and the management of erosion as a result must be detailed and a management plan agreed upon.

Liability

Liability as landowner must be considered, while landowners cannot be held responsible for the actions of their employees, agents, invitees or neighbours. This is in terms of damage to infrastructure caused by amongst other things fire, hunting, accidents, et cetera. The risk of crop damage (fire) and insurance as a result of the project should be considered and detailed.

Access to services (water and electricity) must be defined and the cost and usage detailed where applicable. Providing sanitation on site like toilets and removal of rubbish should also be detailed and addressed for the cost of the developer.

Registration of a notarial deed will be affected as the rental agreement will be longer than nine years and eleven months. The cost of registration and removal needs to be stipulated in the agreements and covered by the tenant.

Local stakeholders will be included in the approval process and be income beneficiaries. Landowners must try to ensure that their workers extract maximum value as beneficiaries and their involvement is to the benefit of the farm and employees. Sometimes this is, however, approached through a community trust where unfortunately the benefits are watered down, and the beneficiaries are all the surrounding communities and subject to government approval.

Only when you fully understand the area and what is being rented, will you understand the implications – be they short, medium, or long term. One must bear in mind that these agreements for renewable power generation are long term at 25 years and longer, with construction periods being up to two years. The finalisation period can also span over several years. The apparent gains and remuneration must and can only then be weighed up against the commitment and possible negative consequences. Do not enter into these agreements lightly and be coerced by the proverbial carrot in front of the donkey. There is, however, a real possibility for landowners to get involved in renewable power generation and secure a substantial passive income.

For reference and further reading visit https://www.ipp-projects.co.za/

Did you know?

- Wind energy is one of the most cost-effective renewable energy sources.

- One megawatt (MW) of wind energy equates to 2 600 fewer tons of carbon emissions, based on its comparison with coal-fired energy generation.

- Wind power is one of the fastest-growing sources of electricity production in the world.

- Unlike almost all other forms of energy, wind energy uses virtually no water.

- Most wind farms are erected on private land.

- Wind turbines can stand as tall as 200 m.

- Wind turbines generally produce energy when winds blow between 13 km/h and 90 km/h, after which they stop operating.

- Modern wind turbines produce 15 times more electricity than the typical wind turbine did in 1990.

- Wind turbine operational costs are minimal once erected.

- Wind energy is one of the oldest forms of renewable energy generation, used since the time of ancient mariners sailing the world and to power windmills for the pumping of water and grinding of grain since 2000 BC.

- Wind energy theory was discovered in 1919 by German physicist Albert Betz and published in his book Wind-Energie.

Source: klipheuwelwind.co.za