Free State

Dr Miekie Human, Research and Policy Centre, Grain SA

Dr Miekie Human, Research and Policy Centre, Grain SA Dr Godfrey Kgatle, Research and Policy Centre, Grain SA

Dr Godfrey Kgatle, Research and Policy Centre, Grain SAThere is no silver bullet for managing Sclerotinia stem and head rot of soybean and sunflower. However, during a recent Sclerotinia research day on 13 October 2022, industry members, researchers and producers discussed several integrated pest management (IPM) approaches which producers could implement to manage epidemics. Integral to developing an IPM system is to understand host-pathogen-environment interactions (referred to as the disease triangle) and factors driving disease establishment in the field.

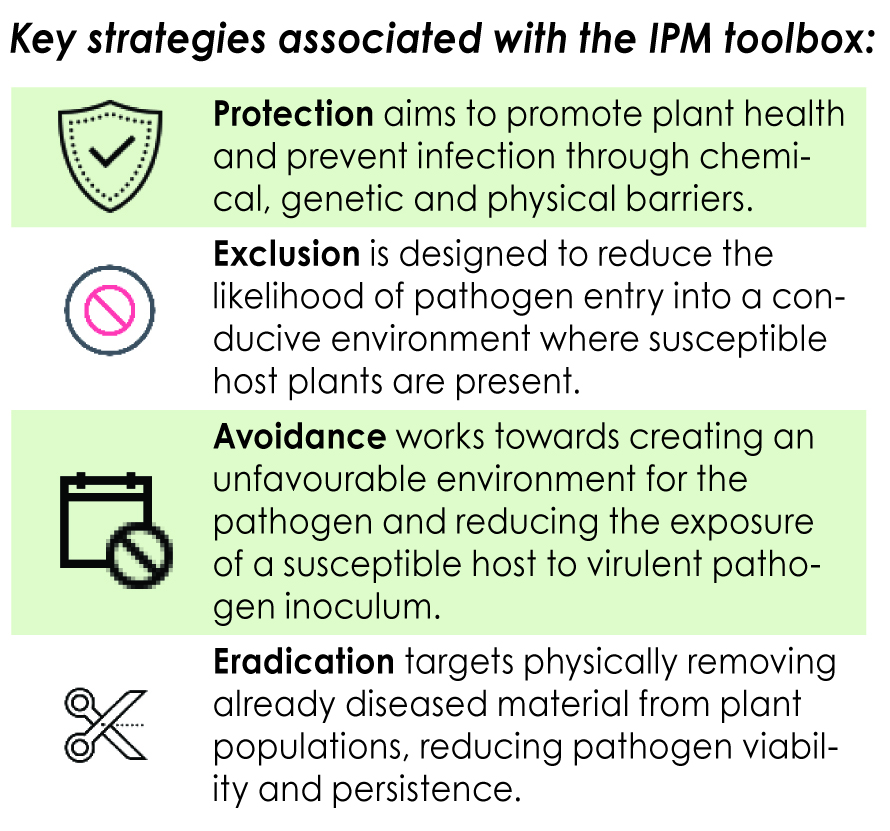

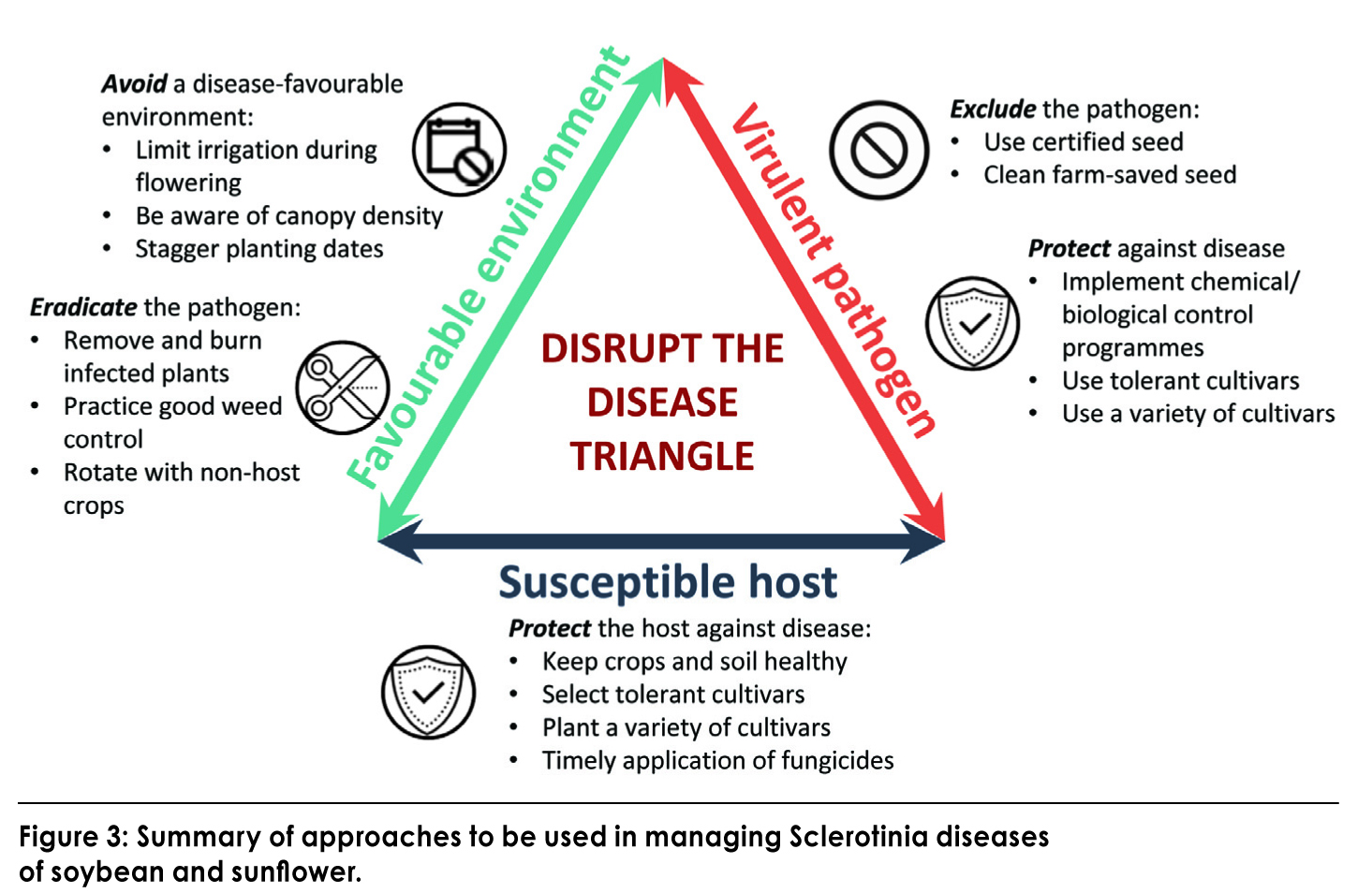

IPM calls for producers to protect crops while disrupting the disease triangle through (i) focussing on the strengths of the host, (ii) weaknesses of the pathogen and (iii) creating environmental conditions that are unfavourable for disease development. Disrupting the interactions or destabilising one of the three key factors (host, pathogen, environment) results in an incomplete triangle that mitigates or limits disease occurrence. Plant disease will not develop if there is no viable pathogen, no susceptible host plant or if there are environmental conditions unfavourable for the pathogen. The purpose of this article is to provide producers with interventions for their IPM toolbox that could assist in decision-making for disrupting the Sclerotinia disease triangle.

1. Know your enemy

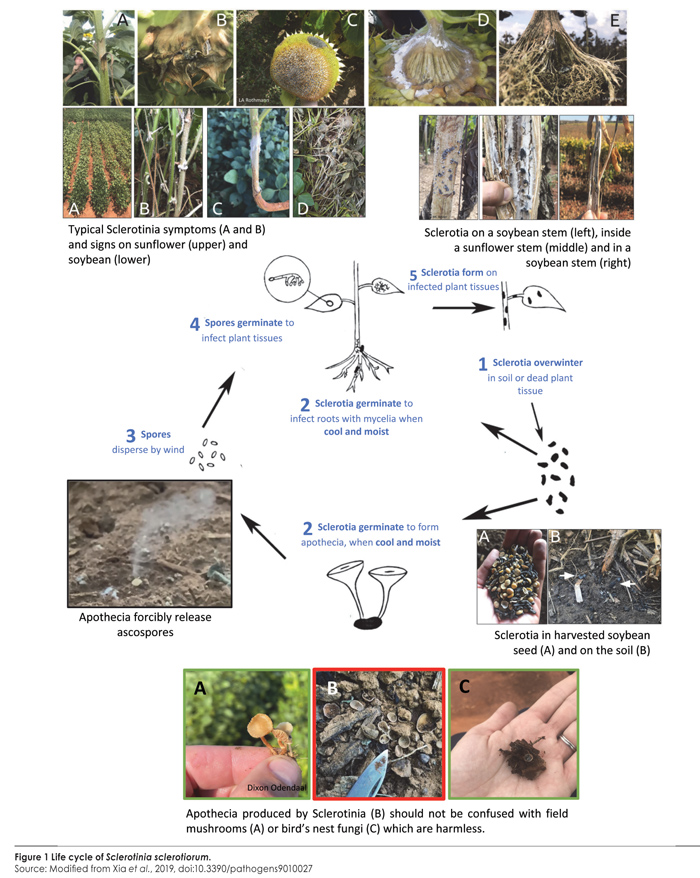

A good understanding of the Sclerotinia life cycle and chain of events that lead to disease development is important for producers to intervene and slow the spread of the disease. The typical Sclerotinia lifecycle includes the following stages as seen in Figure 1:

- Sclerotinia is introduced into the field by sclerotia (black and hardened survival structures, normally found within infected soybean stems, sunflower heads or sunflower stems). Most often, disease

occurs because of spores present in the field, rather than because of spores being blown by the wind from neighbouring fields. - When the environmental conditions are favourable for disease development (cool and moist), sclerotia germinate to either infect the roots via mycelia (white cottony filaments of the fungus) or to form mushroom-like structures called apothecia (which host the spores).

- Spores are dispersed by the pathogen forcibly ejecting them when air currents move over the apothecia, spreading spores via wind. It is important to note that these spores are not as hardy as those of other pathogens (such as rust), and some studies have found spores to travel only very short distances (3 m – 100 m) from their point of origin.

- Upon the successful dispersal, spores land on the susceptible tissue of the host plant to initiate infection. Spores then germinate, which enables them to enter the host and grow into host tissues. Successful disease establishment is marked by water-soaked lesions on stems and heads caused by cell wall-degrading enzymes produced by S. sclerotiorum.

- Sclerotia form as the growing season ends, or when conditions are no longer favourable for the disease. Sclerotia formation is associated with diseased plant material and are dislodged to the soil surface, where they can germinate in following seasons if conditions are conducive. Sclerotia can survive in the soil for many years (eight or more). Therefore, the disease may build up over time.

Various tactics exist within each of the above strategies to disrupt the Sclerotinia triangle (Zadoks & Schein, 1979). Key tactics within the various strategies that were suggested at the Sclerotinia research day are discussed below.

Various tactics exist within each of the above strategies to disrupt the Sclerotinia triangle (Zadoks & Schein, 1979). Key tactics within the various strategies that were suggested at the Sclerotinia research day are discussed below.

Environmental conditions that limit disease formation

Environmental conditions that limit disease formation

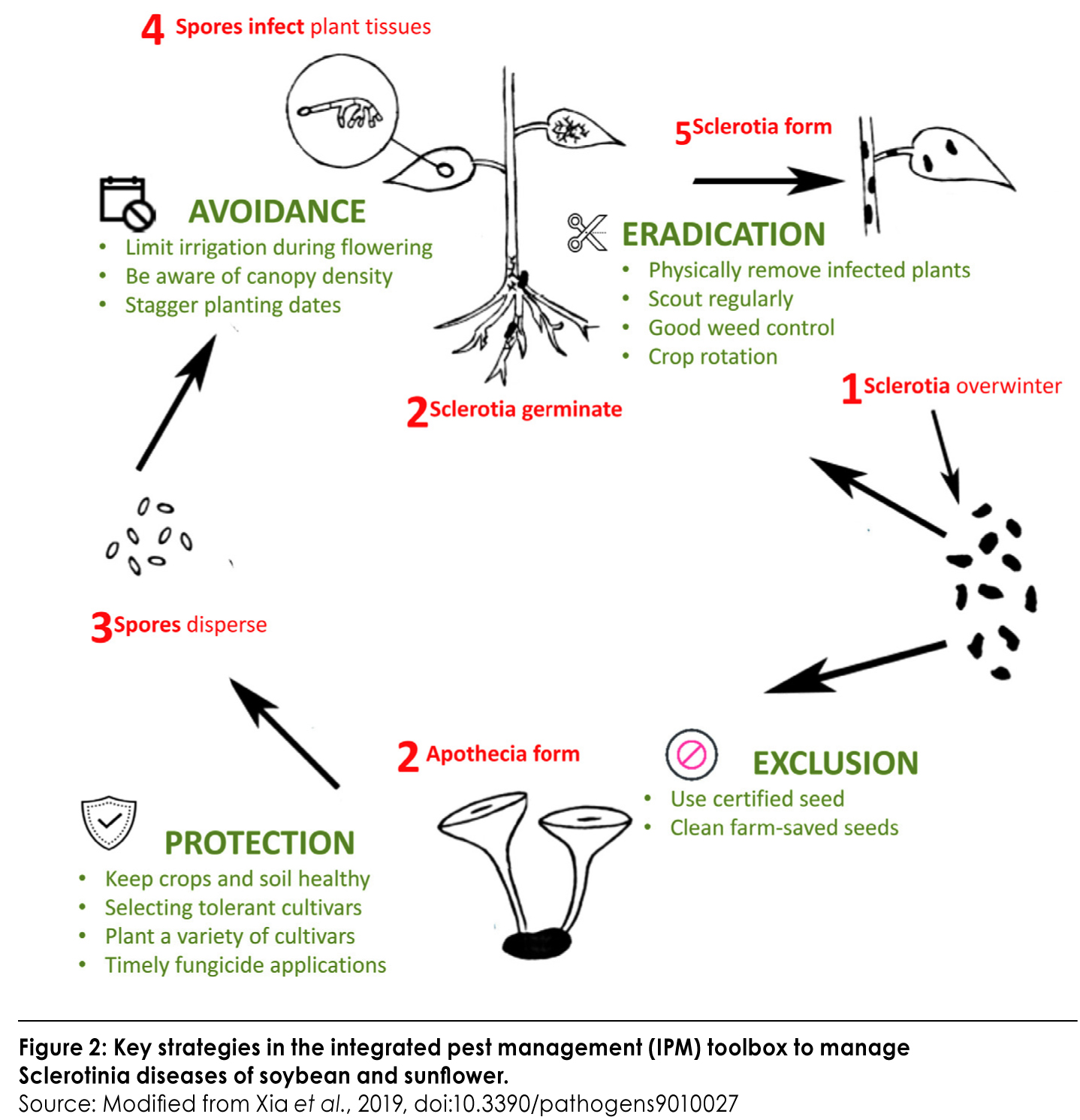

Sclerotinia thrives in a cool and moist environment. To disrupt the suitable environment for the pathogen, the formation of an overly dense soybean canopy should be avoided. The canopy provides the ideal microclimate for sclerotia to germinate to form apothecia. The apothecia release and spread spores to infect host crops. Tactics within the avoidance strategy which can disrupt the interaction between the pathogen and the conducive environment, include planting wider rows to minimise canopy density and avoiding the excessive use of nitrogen (as it promotes vegetative growth of plants, thus leading to the formation of a denser canopy). Minimising dense canopies will further allow for the chemicals and sunlight to filter through and penetrate the ground, reducing soil moisture and the exposure of sclerotia to optimum conditions to germinate (Figure 2).

Soybean and sunflower are normally susceptible to Sclerotinia diseases from flowering to flowers dying off. Therefore, planting earlier and staggering planting dates are recommended to avoid the co-occurrence of spore release during the rainy summer days and flowering. Staggering planting dates may therefore be a useful tool to distribute risk, as multiple planting dates may help to avoid infection windows. Additionally, avoid irrigating during the flowering period as this may favour the germination of sclerotia, encouraging apothecia development and ascospore release.

Soybean and sunflower are normally susceptible to Sclerotinia diseases from flowering to flowers dying off. Therefore, planting earlier and staggering planting dates are recommended to avoid the co-occurrence of spore release during the rainy summer days and flowering. Staggering planting dates may therefore be a useful tool to distribute risk, as multiple planting dates may help to avoid infection windows. Additionally, avoid irrigating during the flowering period as this may favour the germination of sclerotia, encouraging apothecia development and ascospore release.

Planting crops with different maturity groups can also be used to escape conducive disease windows during flowering and senescence. International research has shown that planting early maturity groups (MG 4 – 4,5) during the normal planting period (between middle October and end November) results in completion of flowering and pod formation by the time environmental conditions are conducive for germination of sclerotia, formation of apothecia and ultimately release of spores. (Earliest reports of apothecia in Clocolan and Delmas by the UFS research team include mid-January to as late as May, which may be relevant for sunflower producers.) Disease may be escaped as the fungus, which exploits natural openings at flowering to enter the plant, will not be able to do so as flowers are absent during this conducive period.

Unfortunately, such early maturing groups are not suited to many areas in South Africa. Annual cultivar evaluations are conducted by the ARC-Grain Crops (to assess cultivar responses across different production regions) and the University of the Free State (to determine the tolerance of different cultivars to Sclerotinia), which can be leveraged each season. Click on the QR code to access the SA Graan/Grain cultivar trial insert (https://sagrainmag.co.za/cultivar-trial-inserts/) or visit sagrainmag.co.za.

Unfortunately, such early maturing groups are not suited to many areas in South Africa. Annual cultivar evaluations are conducted by the ARC-Grain Crops (to assess cultivar responses across different production regions) and the University of the Free State (to determine the tolerance of different cultivars to Sclerotinia), which can be leveraged each season. Click on the QR code to access the SA Graan/Grain cultivar trial insert (https://sagrainmag.co.za/cultivar-trial-inserts/) or visit sagrainmag.co.za.

2. Support the host

Supporting overall plant and soil health can aid the plant in fighting off the disease, although this alone will not provide full protection against Sclerotinia diseases. Selecting cultivars which are well-adapted to a specific environment is pivotal to ensuring a stable yield, as soybean and sunflower cultivars are known to differ in their responses to different environments. Additionally, utilising the data generated from the ARC-Grain Crops cultivar evaluations, cultivars that perform stably across environments can be selected. This will help reduce the risk associated with unstable cultivar responses, as producers can understand what can be expected from a host.

The selection of resistant cultivars, where available, is always recommended as a chief tactic of host plant protection. Although, there are no soybean or sunflower cultivars that are fully resistant to Sclerotinia diseases, some cultivars are more tolerant than others. Tolerance (where varieties of a crop suffer less by way of losses than others at the same disease severity) is used in cases where complete resistance is lacking. It is also recommended to plant more than one cultivar per season to mitigate the risk of disease spread. In the last few seasons, numerous new soybean and sunflower cultivars have become available. For the 2021/2022 season, 25% of soybean cultivars entered into the cultivar evaluation trials were new. Therefore, it is critical for researchers to explore new sources of resistance and understand cultivar yield responses.

3. Limit pathogen presence

It is important for producers to manage pathogen inoculum under field conditions. Inoculum refers to the spores released by apothecia (formed from sclerotia). Spores can also be blown by the wind from surrounding fields outside of a producer’s control, although in the case of S. sclerotiorum, such long distances are unusual. Scouting throughout the season is important to maintain records of where Sclerotinia diseases occur and to what extent. Producers can attempt to manage the inoculum load in a field by selectively eradicating or removing and burning heavily infected plants (if there are only a few) and planting non-hosts in following seasons to reduce sclerotia persistence. Additionally, mapping out and keeping track of areas which are often infected, is a useful way to target specific areas and refrain from planting susceptible crops in those areas. Weed control is also important, as many weeds are hosts to Sclerotinia. Those confirmed in South Africa are the common blackjack (Bidens pilosa), common cosmos (Bidens formosum), pigweed (Amaranthus deflexus) and tall khakibos (Tagetes minuta).

There are registered fungicides for the control of Sclerotinia diseases. However, these are limited for soybean and only a seed treatment is available for sunflower. Procymidone is registered against Sclerotinia stem rot of dry beans, green beans, soybeans and peas. Benomyl is a registered seed treatment for sunflower, but it has been taken off the American and Australian markets due to the high toxicity.

In South Africa, certified seed may not contain more than 0,2% sclerotia, and seed treatments are applied to keep seed as healthy as possible. Planting certified seed can help limit pathogen presence in fields. When retaining soybean seed, be aware that saving seed from Sclerotinia-infected fields may lead to sclerotia in the seed being replanted in the next season. Therefore, seed sieving is recommended to reduce sclerotia loads. Furthermore, S. sclerotiorum is known to be seed-borne and this can be a particular risk for retained seed if it is not properly cleaned. Sclerotia harvested from the previous season can spread the disease across fields when replanted. Proper cleaning of equipment after harvesting infected fields is also important to remove sclerotia that may be lodged in the equipment.

So, what to do now?

-

- Keep records of where Sclerotinia infections occur in each season. If possible, avoid planting susceptible hosts in those fields.

- Scout, scout, scout!

- From two weeks prior to flowering, inspect fields on a regular basis to see if apothecia are present. If you see apothecia, be aware that spores will be present and if flowering still needs to occur, plants are at risk for disease to develop.

- After flowering, monitor fields for symptoms and signs of disease. If only a few plants show clear disease symptoms, remove and burn these to prevent the build-up of the pathogen in the field.

- Follow the South African Sclerotinia Research Network (SASRN) on Facebook and connect with us. Send us photos of your observations and report sightings of apothecia in your area.

- Distribute your risks

-

- Plant a variety of cultivars.

- Planting at different dates may help to escape disease in some fields.

- Consider the tools above and how these can be used on your farm to disrupt the disease cycle.

-

- Distribute your risks

Summary

In managing Sclerotinia diseases, producers are urged to limit pathogen presence, support the host and create an environment which is unfavourable for disease development.

Contact Dr Lisa Rothmann at CoetzeeLA@ufs.ac.za or 079 270 9691 or Dr Miekie Human at miekie@grainsa.co.za or 067 016 9493 for further information. Visit the SASRN website at sclerotinia.co.za or Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/sclerotiniaZA) for updates.

References

-

-

- Roper, M et al. 2010. Dispersal of fungal spores on a cooperatively generated wind. 107(41), 17474 – 17479.

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1003577107 - Rothmann, L. 2020. Alternative hosts associated with Sclerotinia sclerotiorum – weeds

http://sclerotinia.co.za/article/alternative-hosts-associated-with-sclerotinia-sclerotiorum-weeds - Zadoks, JC & Schein, RD. 1979. Epidemiology and Plant Disease Management. New York: Oxford University Press.

Additional resources

-

- Dr Rothman and Dr Human. Sclerotinia alert: Is 2022 a good year for an outbreak?

https://sagrainmag.co.za/2022/02/14/sclerotinia-alert-is-2022-a-good-year-for-an-outbreak/ - Prof Flett. 2022. Sclerotinia head and stalk rot increasing

https://www.arc.agric.za/Agricultural%20Sector%20News/Sunflower%20-%20Sclerotinia%20head%20and%20stalk%20rot%20increasing.pdf - Dr Bester and Dr Rothman. 2019. Management of Sclerotinia head and stem rot

https://sagrainmag.co.za/2019/02/20/management-of-sclerotinia-head-and-stem-rot/ - Ramusi & Flett. 2015. Sclerotinia disease of sunflower: a devastating pathogen

https://www.grainsa.co.za/sclerotinia-disease-of-sunflower:-a-devastating-pathogen - Sclerotinia research: then and now

https://sagrainmag.co.za/2021/08/31/sclerotinia-research-then-and-now/

- Dr Rothman and Dr Human. Sclerotinia alert: Is 2022 a good year for an outbreak?

- Roper, M et al. 2010. Dispersal of fungal spores on a cooperatively generated wind. 107(41), 17474 – 17479.

-