CEO, MIDS, South Africa and vice-chairperson, PRF

Lupins represent a cool-season crop that may grow in regions where soybeans would not prosper. In the early years of lupin production, lupin grains were grown in rotation with other crops such as cereals. This benefits the farming system by reducing disease in cereal crops, increasing the supply of organic nitrogen as well as increasing the supply of high-quality sheep feed (White et al, 2008).

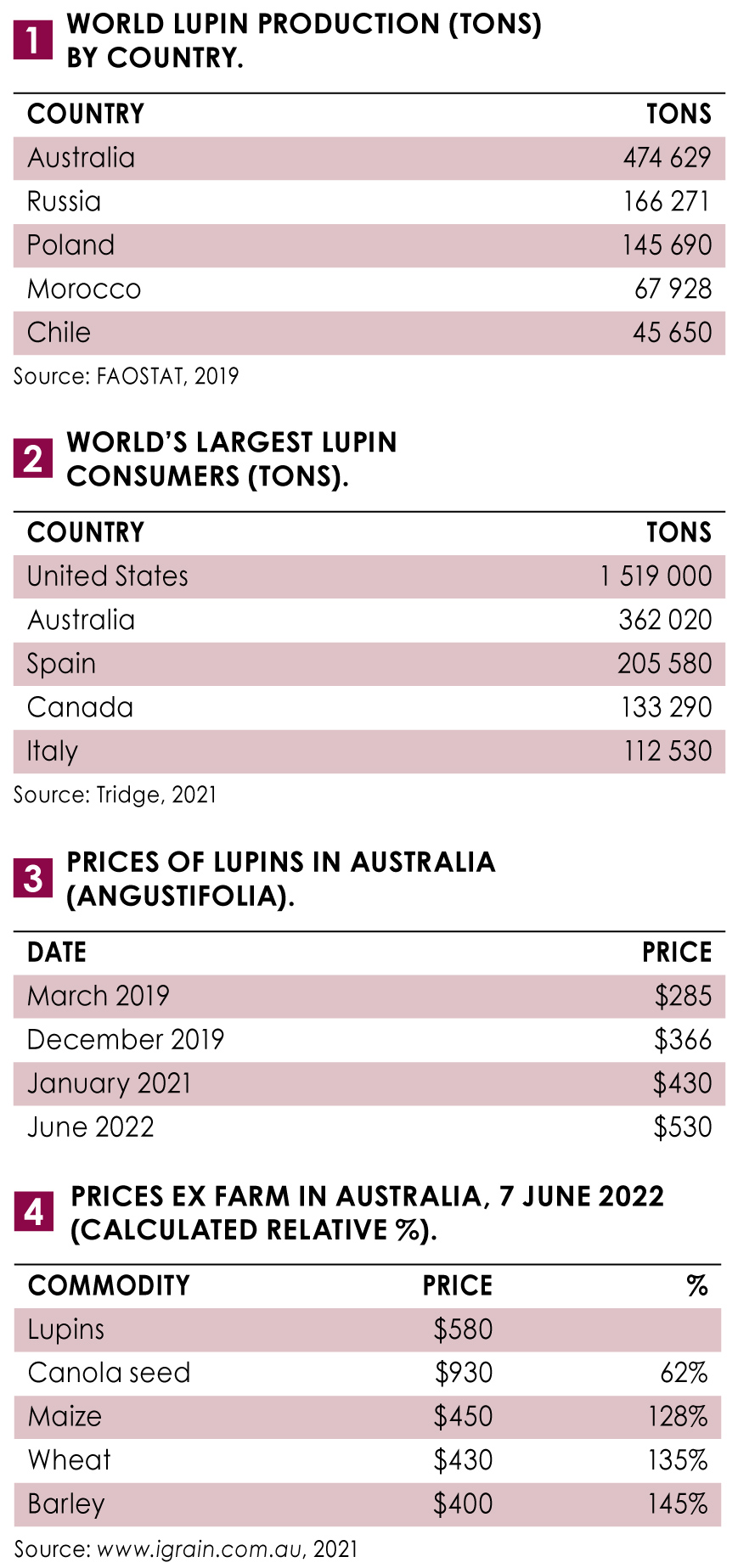

Common all over the world, lupins are legume crops with an annual production of 1,2 million tons (FAOSTAT, 2019). The five largest producers in 2019 are listed in Table 1.

Impediments to increasing lupin availability include lack of local knowledge by crop producers and those feeding livestock, as well as anti-nutritional factors. A sustainable market must be established for producers to devote to lupin production.

Lupins can be fed without processing and although dehulling is preferred, it is not essential. The hull fraction represents approximately 25% of sweet lupins – lupin meal (un-dehulled) will therefore contain more fibre and less protein than soybean meal.

Leguminous crops including lupins are an important source of protein and other nutrients. The coexistence with nodule bacteria Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) results in the capability of synthesising protein by acquiring molecular nitrogen from the atmosphere. There are a large variety of lupins which differ in their qualitative and quantitative structure (Kurlovich, 1998). The nutrient content of lupins differs considerably between species, variety, and location (Kurlovich et al, 2006).

Lupins are also promoted as human food, with medical studies confirming the benefits in combatting high blood sugar, heart disease and obesity.

There are mainly three types of lupins produced commercially: white lupin – L. albus; yellow lupin – L. luteus; and narrow-leafed lupin – L. angustifolius. The nutrient content, including protein and energy, varies significantly between these types of lupins, which has a major effect on their nutritional and commercial market value. It is important to determine the commercial value differences as part of the decision process of which type of lupin to produce.

Global production of lupins

Global production of lupins

The demand for lupin plants is continuously growing due to the increasing popularity of plant-based dietary fibre and proteins in food and beverages. Populations around the world are looking for gluten-free high-fibre diets which is why lupin plants have been gaining worldwide popularity. Multiple food manufacturers are looking to substitute soy protein for lupin protein due to their rich protein profile. Lupins are an alternative to imported feed such as soybeans as they are a cost-effective, safe source of high-protein feed for livestock (Research, 2017).

The largest consumers of lupins globally are the United States (Table 2) followed by Australia.

Production in South Africa

Production in South Africa

Lupins, mainly L. angustifolius and L. albus, have been grown successfully in areas of the Western Cape, particularly in deeper sandy soils. Approximately 20 000 ha of lupins were planted in the Western Cape in the late 1990s. The Free State grew 1 000 ha of sweet white lupin (Killian, 1999). The occurrence of various wilt and root diseases such as Fusarium, Phythium and Rhizoctonia historically limited lupin production potential on heavier soils. Lupins are suited to crop rotation systems with grain crops. It is important to have at least a two-year break before planting lupins again on the same land.

Lupins increase the nitrogen availability for the subsequent cereal crop as well as reducing soil density and stabilising soil aggregates, thus increasing wheat yields (White et al., 1978). Anthracnose (caused by the fungus Collectotrichum gloeossporiodes) became a serious disease in the Western Cape with L. albus being particularly susceptible. The ’narrow leaf’ L. angustifolius was therefore recommended (Hardy, 1998).

The production of L. angustifolius in place of L. albus has a significant impact on the market for lupins with respect to the animal feed industry, considering that L. albus has a significantly higher nutritional value than L. angustifolius (Hill, 1977).

Just after 1947, sweet lupin cultivars were introduced into the Western Cape of South Africa. The effective populations of Bradyrhizobium in the Western Cape were established by widespread cultivation of lupin. In the winter rainfall region of the Western Cape, field trials were carried out at five sites to determine whether inoculation increased yields of L. angustifolius. In moderately alkaline soils, populations were 380 rhizobia g and >5 000 rhizobia g in moderately acid soils.

A lupin inoculant was introduced in the 1960s and contained a VK7 strain. This strain was then replaced by WU425, which is effective on lupin. The South African Rhizobium collection has a VK10 sub-culture strain. However, 30% of producers in the Western Cape rely on naturally occurring soil populations for nodulation. Inoculation can be assumed to be unnecessary if soil populations of rhizobia are large and effective, however, it is beneficial if they are small and not effective (Botha, 2002).

Application in animal feeds

Protein average for white lupins ranges between 33% to 37% with an average of 35%, while yellow and blue lupins have an average of 43% and 33%, respectively. Protein and amino acid digestibility average approximately 85%. Sulphur amino acid and lysine concentration per gram of protein are similar to soybean meal, however, protein levels are lower. Metabolisable energy levels average 2 300 kcal/kg for poultry, with metabolisable and digestible energy for swine at 3 300 kcal/kg and 3 500 kcal/kg, respectively.

Inclusion level of lupins should be adjusted for the age of the animal being fed; inclusions should be restricted in piglet diets while in older pig feeds 10% inclusion would be acceptable. Poultry seem less sensitive to anti-nutritional factors in lupins than pigs. Broiler feed efficiency appears to be affected at inclusion levels of over 20%, while in adult birds, such as layers, higher levels of lupin inclusion is possible (Hess, 2017).

One of the main benefits of lupins as a protein source is that low alkaloid varieties have little anti-nutritional factors and a low level of fibre. No processing or extrusion are required to make the product acceptable for use in monogastric diets. L. albus has a higher protein and oil content with a lower fibre and is therefore of greater nutritional value for monogastric animals (Hill, 1977). Alkaloids are detrimental to effective use of lupins in pig diets and a rapid test developed by Ruiz (1977) can be used to monitor the alkaloid content of lupins.

With some appropriate precautions, lupins can be used in pig and poultry feeds in times of scarce or expensive soybean meal. If lupins are produced in sufficient quantities to provide dependable supply to feed producers, they present a useful protein diversification.

Economics of lupin usage in South Africa

Economics of lupin usage in South Africa

Lupins are highly suitable feed for ruminants if it can be produced at a relatively low cost as is the case in Australia. The relative cost of its high-protein and high-energy combination with virtually no starch can result in lupins making a valuable contribution to the raw material requirements of the animal feed industry.

The composition of the carbohydrates in lupins makes them suitable for the fermentation nature of rumen digestion, while less suited to the acid hydrolysis typical of monogastric animals. The energy recovered in pigs (digestible/metabolisable) is lower than that of ruminants, where it can be as high as cereals in some cases. In the digestive system of poultry, fermentation does not take place, which compromises the energy value that can be extracted in poultry significantly.

L. albus is far more suited for use in poultry feed, where its higher nutrient value and availability will unlock value, while L. angustifolius are ideal for ruminants. Unfortunately, in Australia the main availability is of L. angustifolius and prices obtained are for this variety.

Lupins replace and compete with both protein meals and grains, due to the fact that that they supply both protein and energy. It is therefore difficult to express their value as a ratio to either an oilseed meal or a grain.

The extent of replacement of regular raw materials in animal feed is largely based on price and feed manufacturers use least cost linear programming to determine ‘cut off’ prices for inclusion of lupins. Values are different between various species, so it will be dependent on the type of feeds the potential miller is manufacturing. As a price indication the below relative values could be used as a guideline.

Evaluations done in the study

Relative value to soybean meal

In Western Australia it has been stated that lupins generally compete against soybeans in export markets and are typically valued at 70% to 75% of the price of soybean meal (Government of Western Australia, 2021).

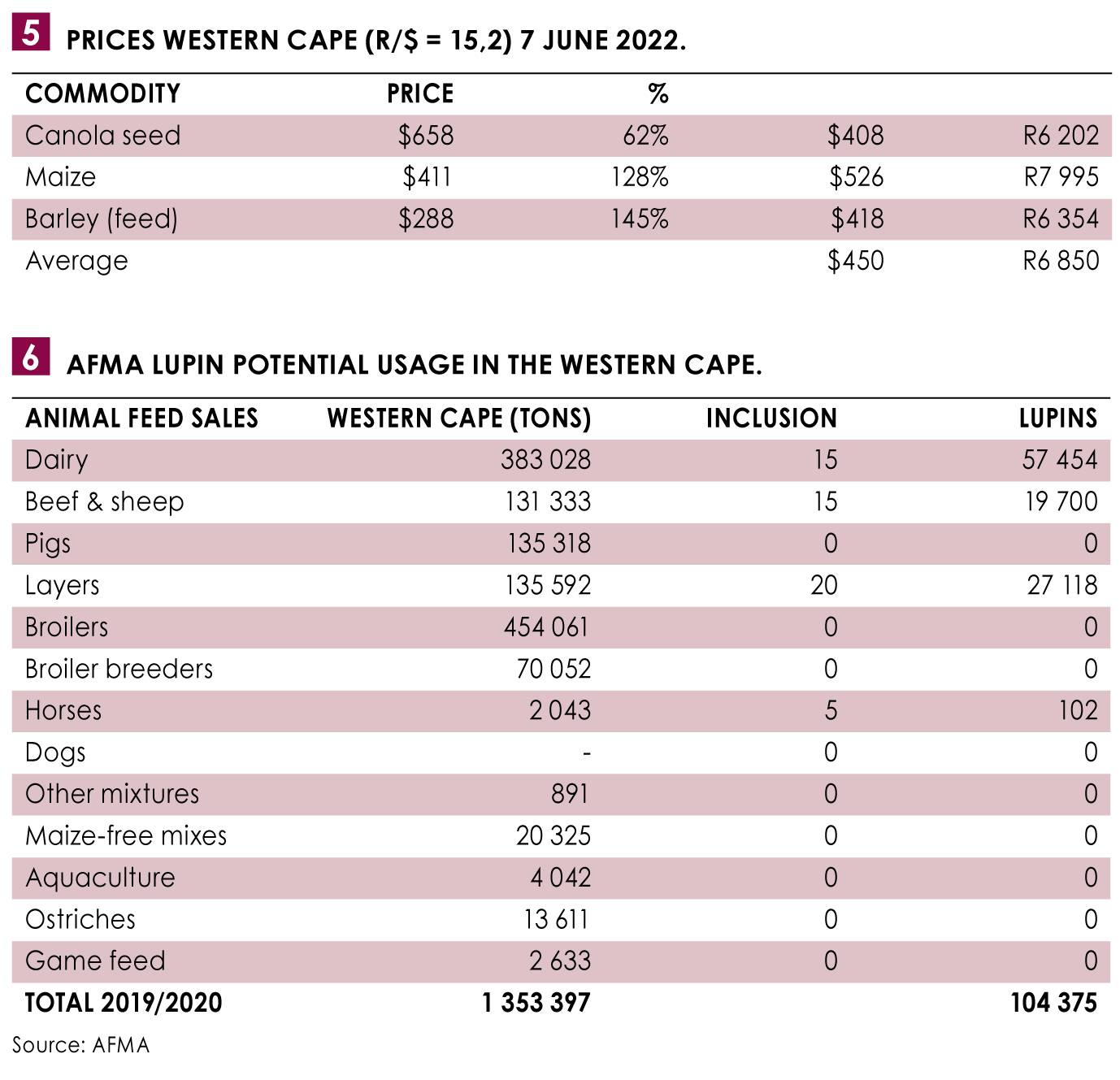

On 7 June 2022, the estimated imported Argentine soybean meal in the Western Cape was R9 700/ton (including 4,9% import duty). At 70%, this would be R6 790/ton, which appears high when compared to domestic canola meal prices.

Lupin feed usage volume maximum potential

Lupin feed usage volume maximum potential

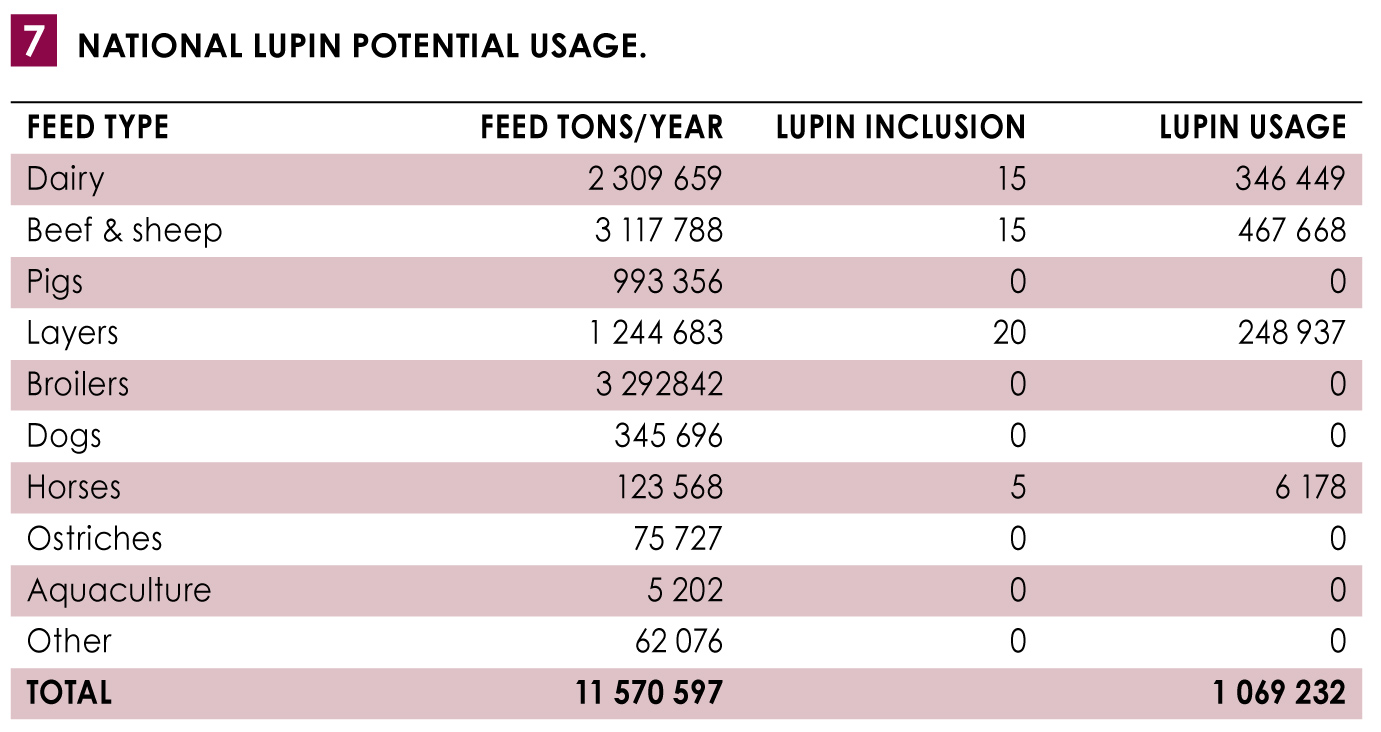

It is important for the industry to attempt to establish the potential volume of usage of lupins in animal feed in South Africa in order to establish maximum usage.

The feed market in the Western Cape will extract the highest market value for lupins which will not require excessive transport to inland markets.

Based on feed volumes of the Animal Feed Manufacturers Association of South Africa (AFMA) in the Western Cape, the immediate potential – should the raw material be readily accepted – is estimated at 104 375 tons. (This is conservative considering AFMA makes up 60% of total feed in South Africa skewed to monogastric.)

The potential usage of lower density protein sources in the inland part of the country is extensive, but price pressure on producers will be high. Sunflower oilcake, which is produced in these regions, is a major competitor.

The maximum potential usage of lupins in the country, considering transport was not an impediment and L. angustifolius is the choice (ruminant animals), can exceed 1 million tons under the correct circumstances.

Conclusion

Lupins will adapt well to growing conditions in the winter rainfall region of the Western Cape and could result in great advantage if used in a rotational crop system, mainly by the supply of organic nitrogen and reducing diseases found in cereal crops.

There are a large variety of lupins that differ in their qualitative and quantitative structure. Nutritive content of lupins differs considerably between species, variety, and location. It is extremely important that there is a coordinated effort by the industry to agree on which lupins will be best suited to South Africa from both a production point of view as well as for the application in the animal feed market.

Both L. angustifolius and L. albus could be grown successfully in the Western Cape in a crop rotation system. Lupins are more suitable for sandy soils rather than heavy soils in order to limit disease challenges.

L. albus has a significantly higher nutrient content resulting in a larger market range and value for animal feed. L. albus is also more suitable for feeding poultry, while L. angustifolius is more suitable to feed ruminant animals and pigs (lower alkaloid level). L. angustifolius contains NSP that lower the digestibility and performance in monogastric animals.

The supplementation of diets with NSP enzymes should be considered to improve performance. Modern varieties with low alkaloid content have made the use of lupins in monogastric diets more accessible. For monogastric animals, lupins are low in energy as well as lysine and methionine which need to be supplemented. L. albus has considerably higher energy, protein and amino acids than L. angustifolius.

It is extremely important that lupins chosen to be grown in South Africa have a reasonable uniformity and that the end user has a reasonable description of the attributes and nutritional value of what they are purchasing.

Lupins replace and compete with both protein meals and grains. The extent of replacing other raw materials is based mainly on linear feed formulation. Based on historical global pricing, it is expected that lupins (L. angustifolius) could obtain a price of 67% of canola seed and 124% of maize.

Currently a price of R6 500 could be used in a feasibility study to evaluate if the production of lupins could be economically viable.

The Western Cape could more than double its lupin usage to over 105 000 tons. The potential usage for the country is beyond any production envisaged should the price be competitive.

References available on request.