agricultural economist,

Graan SA,

cathrine@grainsa.co.za

07/07/2025

SOUTH AFRICA IS EXPECTED TO IMPORT YELLOW MAIZE AGAIN IN THE 2025/2026 MARKETING SEASON. THIS IS THE SECOND CONSECUTIVE SEASON WHERE IMPORTS ARE REQUIRED. SUPPLY AND DEMAND ESTIMATES INDICATE THAT THIS IS A SHORT-TERM CORRECTION FOLLOWING DROUGHT-INDUCED SUPPLY PRESSURES, AND NOT A STRUCTURAL SHIFT IN DOMESTIC PRODUCTION OR DEMAND.

The 2024/2025 production season was expected to be a season of recovery for most crops. However, due to delayed rains during the critical growth stage in the prior season, South African producers missed the maize planting window, leading to a decline in the area planted of yellow maize.

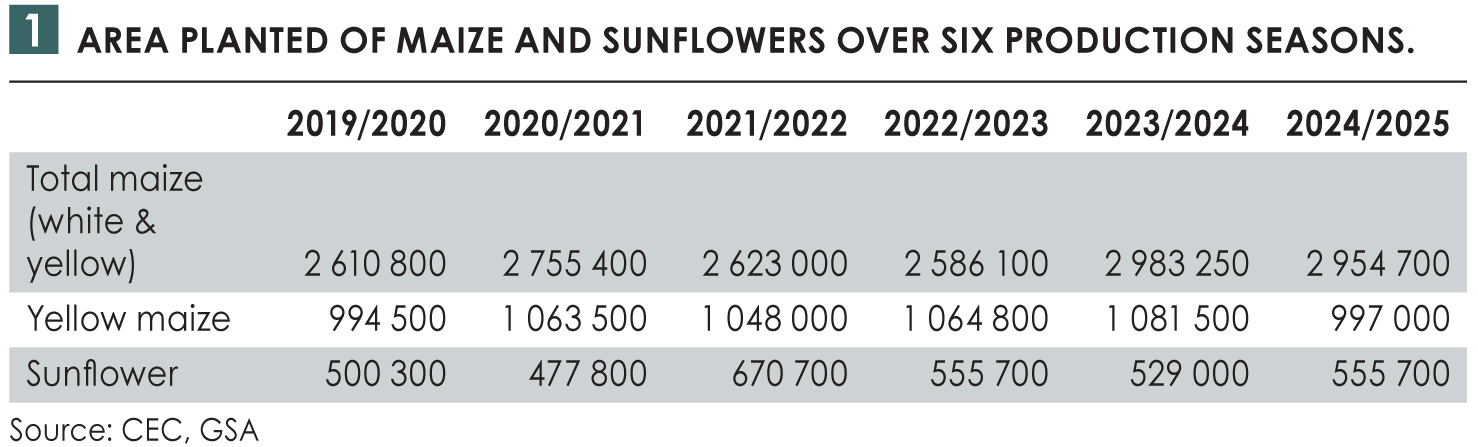

According to the fifth production estimate released by the Crop Estimates Committee (CEC), the total area planted of yellow maize for the current season is 997 000 ha, an 8,13% decline from the 1 081 500 ha planted in the 2023/2024 season (see Table 1). In contrast, the area planted of sunflowers increased by 4,92%. The switch to planting sunflowers was primarily influenced by climatic conditions which favoured shorter-season crops, and attractive global oilseed prices. At the end of October 2024, sunflower Safex prices peaked above R10 000/ton for the first time since February 2023.

Why did South Africa import yellow maize in the previous marketing season?

Why did South Africa import yellow maize in the previous marketing season?

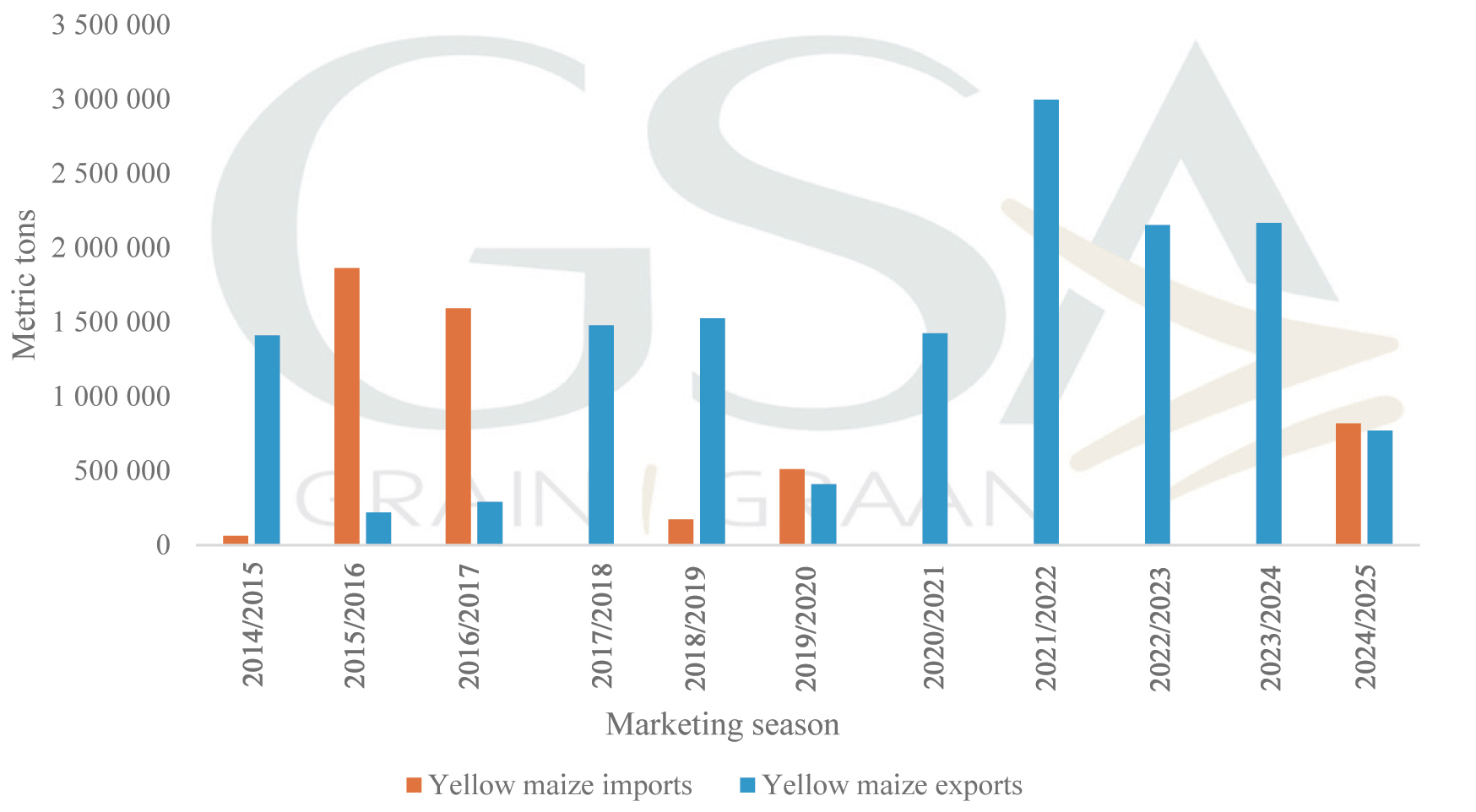

Yellow maize imports are not unusual for South Africa. Historically, the country is known as a net exporter of yellow maize, maintaining self-sufficiency over the past several years. In fact, the country had not imported yellow maize for four consecutive seasons prior to the 2024/2025 season (See Figure 1).

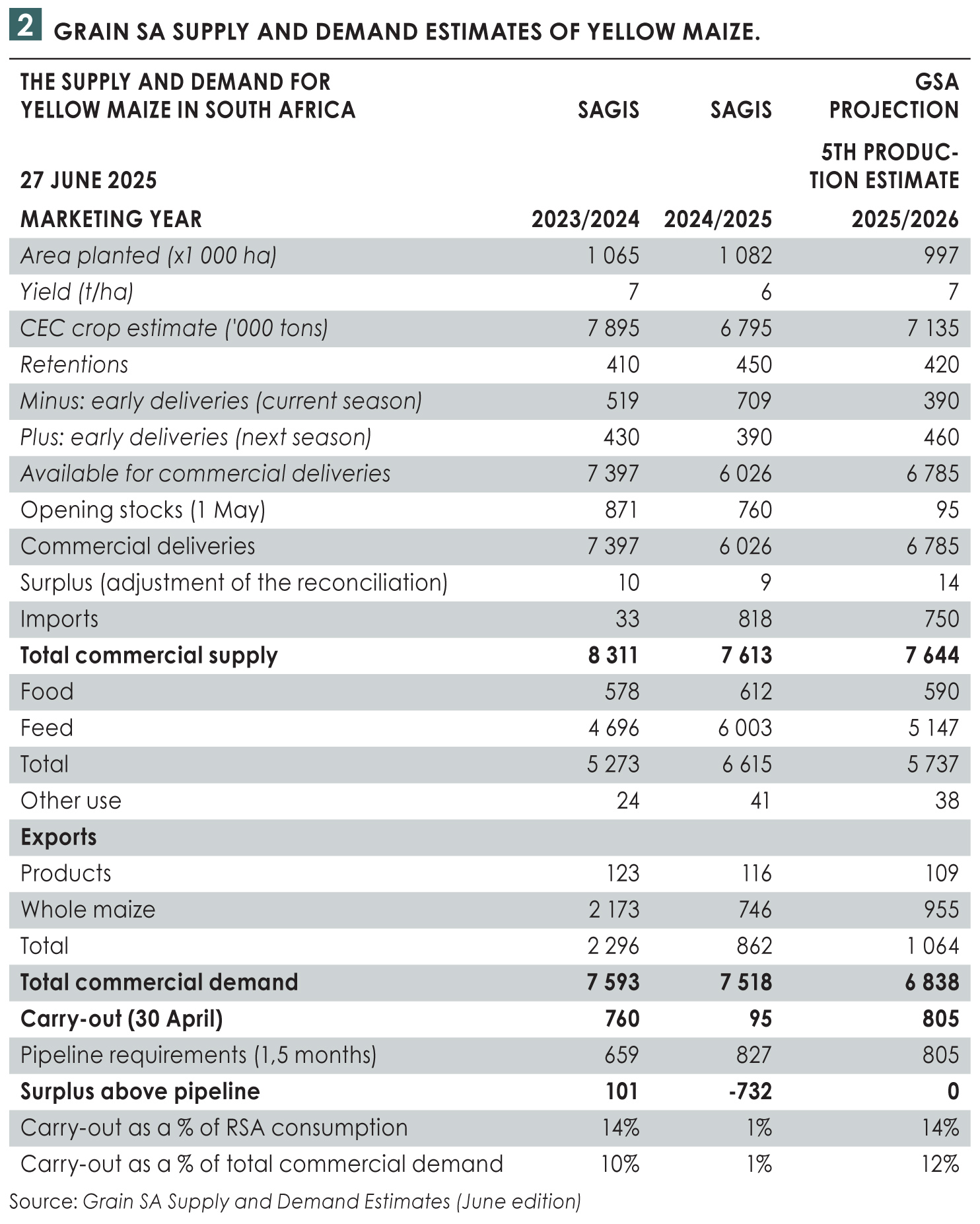

The previous season marked the first year in five years where imports were required, and now, for a second consecutive year, the country will again supplement a portion of its domestic stocks with imports. To be more specific, 9,81% of the total commercial supply will be supplemented by imports in comparison to 10,74% in the previous season (see Table 2). Average production significantly decreased due to the 2023/2024 mid-summer droughts. This resulted in a domestic shortfall from lower commercial supply, 8,3 to 7,6 million tons (2023/2024 to 2024/2025) and lower opening stocks (Table 2). As a result, 818 809 tons of maize were imported to replenish supplies, mainly sourced from:

- Argentina: 705 190 tons

- Brazil: 105 707 tons

- The United States: 7 912 tons

Source: GSA using SAGIS data

The imported yellow maize was consumed locally to meet demand (and not re-exported). The demand was primarily from the animal feed manufacturing industry, which consumed 6 million tons in the previous season.

The imported yellow maize was consumed locally to meet demand (and not re-exported). The demand was primarily from the animal feed manufacturing industry, which consumed 6 million tons in the previous season.

Interestingly, exports continued despite these imports. In the 2024/2025 season, South Africa exported 770 377 tons of yellow maize, mainly to Zimbabwe, Botswana,

Eswatini, Mozambique, Namibia, and Lesotho. For the current 2025/2026 season, the South African Grain Information Service (SAGIS) data revealed that as of week 8, 141 058 tons have already been exported to these neighbouring countries, along with deep-sea exports to Korea and Vietnam.

The dual-trading activity (importing maize while simultaneously exporting)

raises the question on why South Africa will be exporting maize while domestic stocks still have to be supplemented.

Why does South Africa continue to export maize even though the stocks have to be supplemented by imports?

The main reason lies in regional free trade agreements, such as the COMESA-EAC-SADC Tripartite Free Trade Area Agreement and the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). These agreements, along with commercial trade obligations and South Africa’s strategic role as a reliable crop supplier within the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region, drive the exports. These exports are important for ensuring food security beyond South Africa’s borders and to help maintain market access and stabilise prices.

Another reason is the pursuit of higher profit margins in a free-market system. Unlike other countries where farmers receive heavy intervention from the government, South African grain producers operate in a free and competitive market. This system allows them to respond to the forces of demand and supply. For example, when there is a shortage in the market or a decrease in production, producers receive a higher price for their maize. The quality of South African maize is among the best in the world, and it is affordable too, giving the country a competitive edge in the international maize market.

If production increased by 5%, why are we anticipating more yellow maize imports?

One significant reason for the need to import maize is the low opening stock level of 95 000 tons at the start of the 2025/2026 marketing year, compared to 760 000 tons in the previous season. This tight starting position resulted from a deficit in the supply chain, particularly with ongoing export commitments and demand, especially in the animal feed industry, which is projected to be lower at 5,1 million tons, thereby alleviating domestic pressure.

Despite this, the total yellow maize production for the 2024/2025 season is forecasted to increase to 7 134 800 tons, up from 6 795 000 tons in the 2023/2024 season. This improvement is attributed to favourable mid-season rainfall, which boosted yields in planted areas. However, it is important to recognise that this is a recovery year following the previous season’s drought-affected harvest, and a portion of this season’s output is still needed to replenish pipeline stocks to meet both domestic and inter-regional demand.

According to the Grain SA June Demand and Supply Estimates, South Africa is projected to import 750 000 tons in the current season. This projection can, however, still change, considering factors such as actual maize deliveries and the recovery rate of neighbouring countries.

To conclude, the expected imports this season are not a surprise, as the country is recovering from the effects of the previous mid-summer droughts. This is not a structural shift or the new norm, as production and yield have increased. This should, however, be a sign to monitor the impact of climate change on crop production, especially maize, and the extent of the effect on producers and other role players.