Conservation agriculture (CA) without cover crops is still the default position for most South African grain producers who follow the principles of zero or minimum tillage, permanent soil cover, and diverse crop rotations. Even in the Western Cape, where more than half of the grain harvest is produced according to conservation principles, cover crops are still a relative novelty.

At the ninth World Congress on Conservation Agriculture (WCCA9), cover crops emerged as a further – albeit powerful – step in the CA journey, with producers introducing these diverse multi-species mixtures and livestock grazing once the fundamentals of the system were well-established.

It is indeed possible to run a successful CA system without ever planting cover crops. This is what Egon Zunckel, one of South Africa’s best-known practitioners of zero tillage and regenerative agriculture, did until a setback in his own business set him on a different path nine years ago. He wryly recalls reading through 15 years’ worth of back copies of No-Till Farmer magazine at the time and noticing for the first time that ‘every single one had an article about cover crops’. Even experienced producers are inclined not to take note of practices they don’t know.

On the other hand, Samie Laubscher, research coordinator of the Western Cape government’s Langgewens research farm, says he has not encountered a single producer who started planting cover crops and then abandoned them again.

A number of local and international speakers at WCCA9 noted the benefits that followed the incorporation of cover crops and livestock in their systems – improved soil structure, increased soil and environmental biodiversity, improved weed control, improved nitrogen fixation in the soil and concurrent improvements in water retention and yield quality, along with reduced crop input requirements and increased grazing capacity.

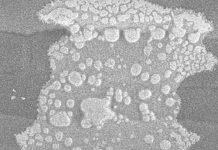

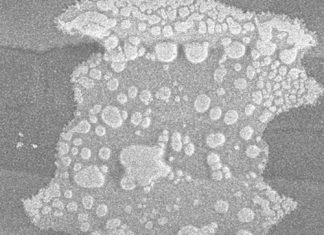

The power of cover crops lies in the diversity of species, as different plants have different nutrient requirements and root morphology, explains Rens Smit, scientific technician at the Western Cape Department of Agriculture. ‘The more diverse the plant species, the less likely it is that they will compete with one another. A grass species has different nutritional requirements from a legume. Plants with a tap-root system, such as brassicas – your radishes and turnips – can source micronutrients, especially phosphates, from deeper soil layers and move them closer to the surface. Once these plants die off and decompose, these micronutrients are then available to neighbouring plants with shallower root systems.’

There are legitimate fears that cover crops may deplete water reserves, but a number of speakers noted that the organic layer of plant matter reduces moisture loss by keeping the soil surface cool and improves soil uptake of rainwater by breaking up and reducing the momentum of falling raindrops, thereby also preventing soil erosion.

A lengthy learning curve

Zunckel has been running a successful CA farming operation for 31 years in KwaZulu-Natal, introducing the practice on every farm his family business acquired subsequently in that province as well as in the Free State.

His experience underscores the fact that such systems are not always problem free. After farming according to these principles on a new farm in KwaZulu-Natal for 14 years, two fields worth of maize plantings failed due to fusarium root rot, a symptom of soil nutrient deficiency caused by years of conventional tillage, possibly aggravated by insufficient leaf disease control. Noting that you cannot solve a problem stemming from tillage with tillage, he instead followed the example of many generations of Free State producers, planting oat seed directly into the failed maize crop with a wheat planter. ‘Since then (for nine years), we’ve been growing cover crops between every single commercial crop we plant.’

For him, even without utilising the oats for animal feed, the cover crops were worthwhile for the soil improvements brought about by their introduction. He was also concerned that livestock may compact the soil. Subsequently, more research and a regenerative agriculture tour to the United States convinced him of the value of livestock in such a system.

‘Nowadays we double crop beef with our maize and soybeans,’ he says. Increased biodiversity and soil organic matter increased the grazing capacity of their Free State land threefold, and on their KwaZulu-Natal land five- to sixfold.

Cobus Bester from Moorreesburg in the Western Cape, who has been farming with grain, cattle and sheep in a conservation system with cover crops since 2016, considers the introduction of cover crops and livestock into a CA system to be a natural progression. ‘Restoring the soil after many years of tillage is a lengthy process. It is best to first establish the CA component and ensure the soil is ready. If you introduce no-till, cover crops and livestock all at once, the animals will trample and compact the soil because it is still too loose after all those years of tillage.’

By the same token, it is possible to do CA without cover crops. ‘Soil cover is key, and you can attain this without cover crops; you have to do minimum tillage, either with a disc planter or a narrow tine, and then use the least amounts of chemical inputs to turn a profit. But there are definite advantages to adding cover crops and livestock. We were able to double our grazing capacity per hectare and raise healthier livestock, while the diversity of plant roots in the soil ensures much healthier soil biology and a healthier build-up of carbon. Without cover crops this process would take much longer.’

Two farming operations on the same land

The timing of cover crop planting can vary depending on environmental circumstances. Whereas a conventional approach is to alternate cover crops and cash crops, a number of South African producers are also experimenting with interseeding. For Magnus Theunissen, a member of the Ottosdal No-Till Club in the North West Province, this practice, which he is trialling on his farm, enables him to ‘run two farming operations on the same hectares’.

Plantings are carefully managed so that cash crops suppress the growth of the cover crops during the growing season. Once the cash crops are harvested, cover crop growth accelerates markedly, and livestock grazing can commence virtually immediately. He concedes this strategy requires careful management. However, the rewards are considerable, and were particularly evident in the most recent season, during which he received only 260 mm of rain, compared to an annual average of 450 to 500 mm. ‘The distribution of the rains was also very bad. For the entire February and March, we only had 18 mm; it was a dreadful season.’

His average maize yield for the season was a measly 880 kg/ha, compared to his usual average of 5 t/ha. However, the interseeded trial plots yielded 2,4 to 2,8 t/ha compared to 600 kg/ha on the monocropped land. In sunflower trials, intercropped fields with biostimulants yielded 1,6 to 2,5 t/ha, compared to 700 kg/ha monocropped. He has been running minimum-till trials on his farm for eight years, and added cover crops and livestock for the past four planting seasons.

Theunissen notes that although cover crops are not widely utilised in his region, the concept is not a complete novelty. ‘In the days when producers still planted their maize in those very wide rows, in my grandfather’s generation, they used to plant radishes and legumes in between the rows, or field beans and oats. They harvested it by hand and fed it to their livestock. It wasn’t that well documented, and over time economic considerations forced farming practices into a different direction.’

Lessons from on-farm trials

Theunissen is one of a number of producers in the Ottosdal No-Till Club collaborating with researchers to explore and refine various aspects of CA. The club was founded in 2008, after a group of producers from the area undertook a study tour to South America to find solutions to severe soil erosion caused by a combination of wide planting rows, strong winds, and sporadic heavy rains on the region’s sandy soils.

Upon their return, they established the club and set about developing and adapting the systems they found in Brazil and Argentina for the region’s unique conditions. This was done through participatory on-farm systems research in collaboration with the Maize Trust, Grain SA and, more recently, ASSET Research.

Dirk Laas, chairman of the club and a speaker at WCCA9, points out that conditions in their part of North West differed drastically from those in South America – with annual average rainfall of 550 mm, but wet seasons with up to 900 mm, and exceedingly dry years like the past season, when some producers received less than 200 mm.

One of the early breakthroughs in the trials was to increase plant density of maize plantings from 24 000 plants/ha (with rows spaced at 76 to 90 cm) to 40 000 plants/ha (rows spaced at 52 cm) in no-till systems. This achieved a speedy build-up of soil cover, more living roots in the soil, fewer weeds, and improved water-use efficiency. Their three-year mean no-till maize yield in these trials was 1,62 t/ha or 52% higher than that of conventional tillage, mainly due to a three- to fourfold increase of the water infiltration rate.

In subsequent trials they have been investigating a number of specific aspects of cover crops and livestock integration, integration, such as:

- Increasing biodiversity in croplands, and investigating the biomass and adaptability of cover crops fulfilling different functions, such as grains, legumes and brassicas, and multi-species mixtures;

- different types of intensification, such as green fallow, intercropping and crop rotations; and

- evaluating different grazing intensities and frequencies.

Over the nine years, Laas says, these trials showed improvements in soil health, both in terms of water quality and nutrient cycles, more and better-quality soil cover, and significant increases in cash crop yield where these plantings followed seasons of cover crops and livestock grazing.

These improved yields went hand in hand with lower agrochemical use, particularly fertiliser, increased biodiversity above and below ground, and extra fodder for cattle. The most promising finding was the potential for overall risk mitigation thanks to diverse modes of income generation, and hence improved financial viability of the farming business over the medium to long term.

From trial to practice

Despite these promising trial results, Laas says these practices cannot simply be transferred wholesale into commercial practice. Because yields are low and margins tight, the livestock component must be run in such a way that it adds value to the overall farming business. ‘Planting the cover crop means you’re essentially putting your soil health in hospital for a year and removing potential profit from your operation. Yes, there are advantages, but that doesn’t mean it is a case of a simple net-profit calculation.’

Grazing cover crops is also management intensive, because the animals must be moved regularly to mimic the non-selective mob grazing that occurs in nature. ‘The theory of CA and cover crops looks feasible, but we are still refining the recipe for North West. The challenge is that the sums must add up,’ he adds.

Cobus van Coller, grain and cattle producer from Viljoenskroon in the Free State, notes that livestock brings in cash and aids in quickly improving the soil. ‘By grazing the land, the livestock stimulates root growth of the cover crops, and the manure and urine improve soil health.’

Producers without a livestock component in their business have the option to bring in livestock from neighbours, or enter into agreements with nearby feedlots to background weaners on their cover crops. Van Coller switched to minimum till with crop rotations in 2006, started planting cover crops in 2016 and added livestock in 2018.

He is adamant that the cover crops should, like a cash crop, turn a profit, and therefore require as much care and forethought as any other facet of the farming operation. ‘What is in the seed mix will depend on what you’re trying to achieve. If your aim is soil health, add more carbon-binding plants such as beans, Japanese radishes, or brassicas. If you are focused more on soil cover, your mix should contain more grasses such as sorghum or babala.’

The seed mix must be of high quality and fit for purpose, otherwise the cost of planting is wasted. For the same reason, the cover crop hectares must be determined by the livestock numbers available to graze it. Having as much diversity as possible within a cover crop mixture is crucial, as diversity below ground adds to the soil structure by enabling channels for new root growth or water absorption and preventing compaction when tractors or livestock move over the soil. ‘Not all mixtures work equally well – some seeds germinate simultaneously and hamper one another’s growth, others don’t germinate at all because of allelopathic interactions with other species.

‘Weed control is also a challenge. Herbicides are not an option once the cover crop mixture germinates, because it contains both broadleaf plants and grasses. Ideally your field must be completely cleared of weeds before you start. The cover crops must also be planted in ideal conditions so that they germinate as soon as possible and are able to suppress any subsequent weed growth.’

Making the switch and remaining profitable

Laas cautions against what he calls an activist approach to CA and cover crops. ‘Some people make it sound easy, and the research results are very convincing, but you also have to protect your business. On-farm trials are instructive, but changes must be implemented in such a way that your business remains sustainable.’

Smit and Theunissen both note that systems with cover crops and livestock are management intensive and require a producer to constantly and closely monitor developments within the cropping systems; it’s not for ‘bakkie producers’ who rarely move within their fields. Moving livestock regularly is also time and labour intensive – another cost component that must be considered.

For Cobus Bester it is imperative that sound financial planning underlies any major change within a farming system. ‘By introducing cover crops, you are effectively taking away from your potential cash crop yield. For us, the additional mechanisation requirement of cover crops was also excessive for our existing hectares. We got around this problem by expanding our hectares by 50%. This enabled us to keep our cropping hectares unchanged and to expand our grazing land.’

Van Coller also warns that machinery should not be the first purchase; it is better to modify existing machinery until the CA system is established. Smit suggests starting small by experimenting with cover crops on low-yield or problematic parts of a farm that could benefit from the accelerated improvements in soil health. ‘We had one field at Langgewens that just didn’t perform as well as neighbouring ones, even though it received all the same inputs as surrounding fields. We planted cover crops, and subsequently it performed much better.’

For Danie Bester, a well-known regenerative producer from Balfour in Mpumalanga, the key to implementing the system was to be adaptive. He made the switch to CA gradually since 2013, starting off by introducing no-till practices in soybeans, where input costs are lower. Three years later, once the system was established, he started following the same principles with maize plantings, and he added livestock to his system in 2018. He also made the distinction between making sure your equipment can adapt to planting conditions, and not the other way around.

He follows a scientific approach, relying on regular soil analysis and intensive production data collection. He adopted precision farming in 2002, dividing his farm into different management zones based on soil type and production outcomes. When input costs started rising exponentially, he was able to use on-farm data to adapt his practices in order to get more value from farming inputs.

By implementing CA and cover crops, he can now produce far more with the same amount of rain, while the permanent soil cover, live roots in the soil, and improved soil biology have also given him a wider planting window.

The big picture

At the WCCA9 and NAMPO Harvest Day in Bothaville earlier this year, Cobus Bester compared notes with peers from summer grain areas and concluded that even with the best cropping and livestock system, current market conditions make innovation and expansion difficult. ‘Our systems worked very well for ten years. Even during very dry years we were able to keep our stock numbers at a level where there was very little need to buy in animal feed and we kept our soils covered. But then the prices of grains, meat and wool dropped by about 20%, almost simultaneously. In planning for the future, one must be cognisant of the political circumstances, unemployment, and poverty.’

Bester, who trained as an accountant before joining the family business, says even model regenerative farming businesses that incorporate crop rotations, cover crops, and livestock have trouble maintaining a healthy profit margin when red meat prices remain stubbornly low. ‘I had a conversation with a producer from North West and concluded that he shouldn’t really be planting maize at all, the risk is too high; but he is currently sitting with too much grain debt, and the livestock cannot pay it off.’

Nonetheless, he believes any farm can be run profitably, provided the system is refined. For that, financial acumen is key. ‘My aim is profit per hectare, not yield per hectare, and I am constantly managing risk. We consider how many tons of wheat we have to harvest in order to pay our direct production costs.’

For those who want to make the switch, it is important to do research and surround themselves with the right experts.

Dr Stephano Haarhoff is a senior agronomist with the environmental consulting firm Anthesis South Africa and an extraordinary lecturer at the Agronomy Department of Stellenbosch University. He notes a considerable and growing divide between those producers who have been implementing CA systems integrated with livestock for a number of seasons and those still following conventional tillage-based systems, with or without livestock integration.

Heavily indebted producers with scant financial reserves cannot risk transforming their entire farming business within a single season, as one failed crop could put them out of business. It is critical that these changes are implemented in a well-planned manner into each unique farming business.

Meanwhile, those who have been integrating cover crops and livestock into a no-till operation for a number of seasons, are able to sustain operations while tweaking their existing operations to improve efficiencies and overall sustainability. Dr Haarhoff sees a vast need for more expert support to assist and advise producers on transitions that will safeguard their farming businesses.