Research Coordination and NAMPO-Tech,

Grain SA

Prof Johan van Tol,

professor in the Depart-ment of Soil, Crop, and Climate Sciences, Univer-sity of the Free State

Natalia Sharp,

environmental assess-ment practitioner,

Digital Soils Africa

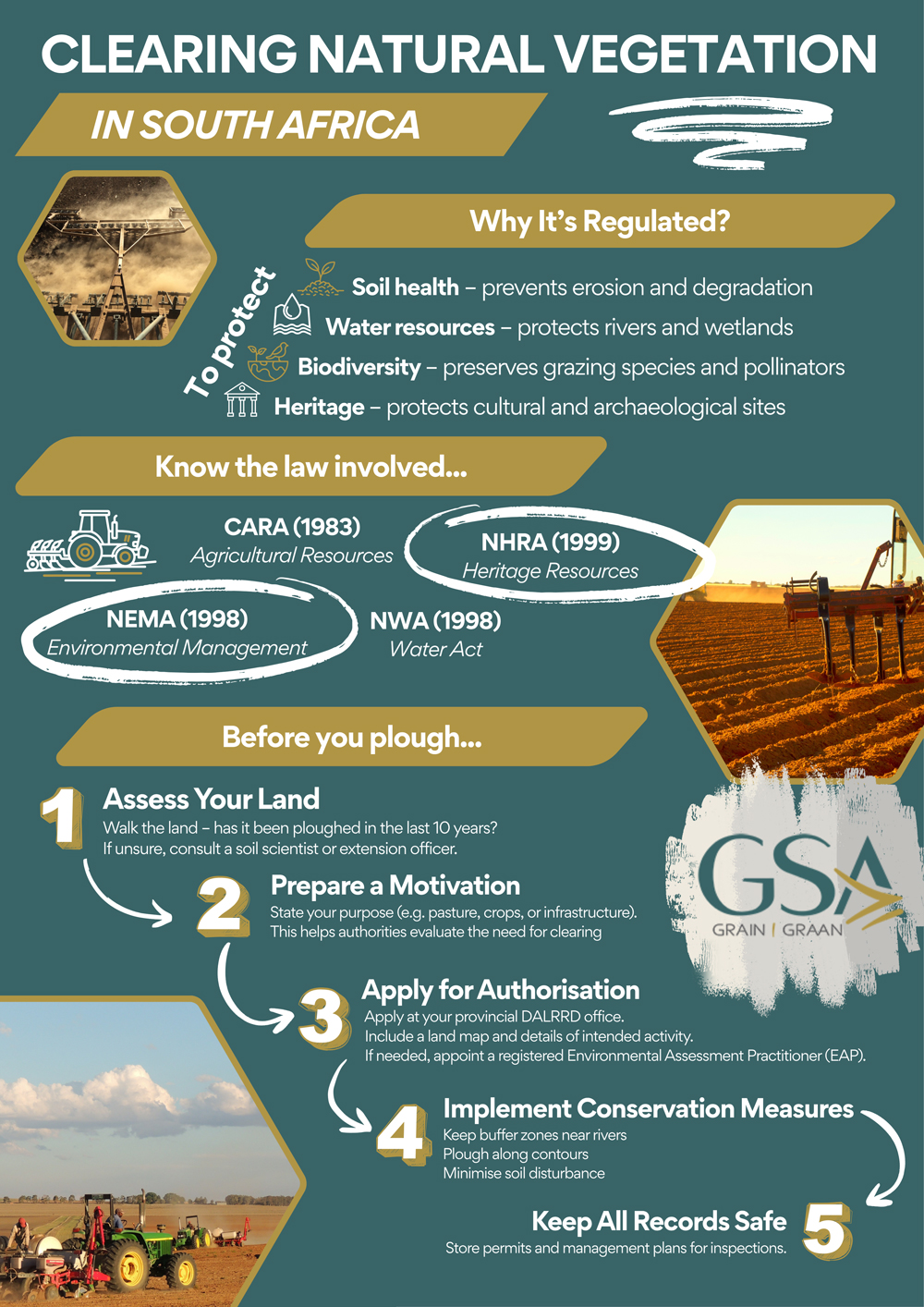

When assessing a piece of land that has never been ploughed, a producer will often focus on the potential: more crops, expanded grazing, or new infrastructure. In South Africa, the decision to clear natural pasture is not just a management choice, it is a regulated action and has legal implications.

Clearing of natural pasture is governed by law under the Conservation of Agricultural Resources Act (CARA), Act No. 43 of 1983. This legislation exists for a good reason: to ensure that South Africa’s agricultural land remains productive for future generations. It is not meant to frustrate farming operations, but rather to safeguard one of the most valuable assets on any farm – the soil.

Why CARA exists

South Africa is a country with limited arable land and highly variable rainfall. Over centuries, millions of hectares of natural pasture have supported livestock production, but they are also vulnerable to overuse and mismanagement. Clearing this land without careful planning can have serious and often irreversible consequences. Once natural vegetation is stripped away, the soil is left bare and vulnerable, making it highly susceptible to wind and water erosion. This process can strip away the fertile topsoil that took centuries to form, leaving the land far less productive.

At the same time, virgin grasslands are rich in biodiversity, supporting a wide range of forage species that sustain livestock and wildlife alike. When these areas are ploughed or disturbed, much of that biodiversity is lost, and the land’s carrying capacity can be permanently reduced. Unregulated clearing can also damage sensitive ecosystems such as wetlands and riparian zones, which play a crucial role in regulating water flow and providing habitat for pollinators and other species essential to a healthy agricultural landscape.

The CARA was put in place to prevent such damage by controlling activities that could permanently alter the agricultural potential of the land.

What does the law say?

In terms of Regulations 2 and 3 of CARA (Government Notice R.1048 of 1984, as amended), cultivation of virgin soil and cultivation of land with a slope greater than the prescribed gradient require written permission from the executive officer.

Under CARA, ‘virgin soil’ is defined as ‘land which in the opinion of the executive officer has at no time during the preceding ten years been cultivated’. Regulation 3 further stipulates that cultivation on slopes greater than 20% is prohibited (stricter conditions apply to erosion-sensitive soils of the Eshowe, Alexandria, Albany, Bathurst and East London municipalities), unless written permission has been granted. In practice, this means that clearing, ploughing, or otherwise altering such land constitutes a controlled activity that requires prior authorisation from the Department of Agriculture (DoA), often referred to as a ‘ploughing certificate’.

However, when the clearing of vegetation or cultivation of virgin soil is done with the intent to expand agricultural production, authorisation is often required from multiple departments and not only from DoA.

Accompanying CARA, the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA), Act No. 107 of 1998, requires environmental authorisation for listed activities, for example the clearing of vegetation over a hectare in areas that are not identified as critical biodiversity areas. Any clearing of indigenous vegetation of more than one hectare will trigger an application for environmental authorisation with the Department of Environmental Affairs. NEMA defines indigenous vegetation as ‘vegetation consisting of indigenous plant species occurring naturally in an area, regardless of the level of alien infestation and where the topsoil has not been lawfully disturbed during the preceding ten years’. This ensures that any large-scale transformation of natural land undergoes environmental assessment to determine potential ecological impacts and necessary mitigation.

At the same time, the National Water Act (NWA), Act No. 36 of 1998, protects South Africa’s water resources by requiring a water use licence for activities that may alter or impact watercourses, including abstraction of water for irrigation, storage of water above certain thresholds, or modification of wetlands or drainage lines.

The National Heritage Resources Act (NHRA), Act No. 25 of 1999, adds an additional layer of protection for South Africa’s cultural and historical environment. Under Section 38 (c)(i) of the NHRA, anyone planning a development that involves changing the character of a site exceeding 5 000 m2 in extent must notify the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA) and furnish it with details regarding the location, nature, and extent of the proposed development. In practice, the heritage authority’s input forms part of the environmental authorisation process, ensuring that archaeological sites, burial grounds, historical farmsteads, and other heritage features are identified, assessed, and where necessary, protected before ground disturbance begins.

For agricultural expansions, this means that ploughing previously untouched land or developing infrastructure such as dams, stores, or packhouses can trigger heritage screening. A heritage impact assessment (HIA) or palaeontology impact assessment (PIA) may be required to identify any artefacts, fossils, graves, or structures older than 60 years, and to recommend appropriate management or mitigation.

To illustrate the different levels of authorisation required, let us take an example of a producer intending to clear and cultivate 15 ha of previously uncultivated land and abstract water from a nearby river for irrigation. This action will require approvals from at least four agencies:

- From DoA: written authorisation for the cultivation of virgin soil under CARA (ploughing certificate).

- From the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE): environmental authorisation under NEMA for vegetation clearance.

- From the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS): a water use licence under the NWA for the proposed abstraction.

- From the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA): a formal comment or notification of ‘No Objection’ or a permit or authorisation under specific sections of the act.

Ultimately, producers who clear land without the required authorisation are, in fact, breaking the law, and the consequences can be severe. Legal enforcement can lead to significant monetary fines, placing an unexpected financial burden on farming operations. In many cases, authorities may go further by issuing restoration orders, compelling producers to rehabilitate the land at their own expense. This process is not only costly but can also take months or even years to complete, delaying any plans for productive use of the land.

In extreme circumstances, where restoration of the natural agricultural resources is deemed essential to meet the objectives of CARA, the Minister of Agriculture has the authority to legally expropriate the land. This means a producer could ultimately lose control of the property in question, underscoring just how seriously the legislation treats the protection of South Africa’s agricultural resources.

The ploughing certificate: often the first step in the development process

Obtaining a ploughing certificate is often the first formal step in the process of expanding cultivation or developing new farmland. While a ploughing certificate is a stand-alone authorisation, it is frequently a precursor to other statutory applications, particularly under the NWA, 1998 and the NEMA, 1998. In most cases, a water use license application (WULA) cannot proceed without proof that the proposed cultivation has first been authorised under CARA. The CARA authorisation confirms that the land is suitable for cultivation from a soil conservation perspective, while the WULA focuses on the sustainable use and protection of water resources associated with irrigation or land drainage.

In this way, the CARA application functions as a foundational phase of responsible agricultural expansion. It ensures that the land in question is environmentally suitable for cultivation before significant investment is made in irrigation infrastructure, storage dams, or crop establishment, etc.

This sequencing also facilitates compliance with NEMA, as any vegetation clearing that exceeds prescribed thresholds will trigger the need for environmental authorisation, either through a basic assessment report (BAR) or a full environmental impact assessment (EIA) process. The CARA application ensures that the specific land parcels proposed for cultivation are accurately mapped and delineated, allowing specialist studies, such as terrestrial fauna and flora assessments, to focus on the precise areas where potential impacts must be investigated. These investigations are often assessed in parallel with heritage and water-use applications.

By starting with the CARA authorisation, producers align their projects with a phased, legally sound development pathway that protects soil, water, and biodiversity resources, while facilitating long-term agricultural sustainability.

How producers can stay compliant

The process may sound daunting, but it is straightforward if approached correctly. Here is how producers can manage it:

1 Assess your land: Walk the land and determine if it is truly ‘virgin soil’. If the land was ploughed or cultivated within the last decade, authorisation may not be required. If in doubt, consult your local agricultural extension officer or check a time series of available satellite images. Professional help can be obtained by appointing a soil scientist that is registered with the South African Council for Natural Scientific Professions (SACNSP).

2 Prepare a motivation: When applying for authorisation, explain why you want to clear the land. Are you planning to establish pastures, plant crops, or build infrastructure? Your motivation helps authorities assess whether the clearing is justified.

3 Apply for authorisation: Submit your application to the provincial DoA office. Include a map of the land and details of the proposed activity. In some cases, an environmental impact assessment (EIA) may be required and a qualified environmental assessment practitioner (EAP) that is registered with the Environmental Assessment Practitioners Association of South Africa (EAPASA) must be appointed to help guide the process and assist in complying with all applicable legislation, not just CARA.

4 Implement conservation measures: If permission is granted, make sure that clearing is done responsibly and according to the law. This could include leaving buffer zones around watercourses, following contour ploughing practices, and ensuring minimal soil disturbance.

5 Keep documentation safe: File your authorisation documents and any management plans. If there is an inspection, you will need to prove that your clearing was legally approved.

The bottom line

For producers, the message is clear: clearing natural pasture is not a decision to take lightly. It is a legally regulated activity that falls under several complementary pieces of legislation designed to safeguard South Africa’s land, water, biodiversity, and heritage. CARA governs the cultivation of virgin soil and steep slopes to prevent soil erosion and degradation; NEMA establishes environmental management principles that guide how vegetation clearance and land-use changes must be assessed, authorised and managed to promote sustainability and protect ecological systems; NWA protects watercourses and regulates irrigation abstraction; and the NHRA ensures that cultural and archaeological heritage is not lost during land transformation.

Together, these laws form an integrated framework that promotes responsible and sustainable agricultural development. Compliance with each act is not merely a bureaucratic exercise, it represents a shared commitment to stewardship, ensuring that South Africa’s natural and cultural resources are protected for future generations. By approaching land clearing through careful planning, environmental consultation, and legal compliance, producers play their part in building a sustainable agricultural sector – one that balances short-term needs with long-term objectives.