Plant breeding has changed significantly in the last 100 years. Just like cars, there are different vehicles to use depending on the desired outcome. Like a classic car, conventional breeding will get you where you need to go; maybe the journey will be longer and with more stops, but you will arrive at your destination. GMOs (genetically modified organisms) are like custom jobs where some parts are sourced from a different car brand. Powerful improvements can be made but this approach can raise controversy. So then – where does the Tesla fit in?

The era of precision breeding

In the world of plant breeding, the Tesla is very much the ‘precision bred’ car of the 2010s. Precision breeding promises faster delivery and more precision using genome-editing tools such as CRISPR-Cas9, which work almost like Tipp-Ex. Using this technology, you can make very precise changes to specific genes; some changes may be very small (e.g., a DNA base change) while others could be more substantive.

Genome editing allows scientists to make targeted changes to a plant’s DNA – no foreign genes, no random mutations. This is different from GMOs, where genes from other species are often inserted. Instead, genome editing fine-tunes what’s already there, enhancing traits such as drought tolerance, disease resistance, or nutrient content. It’s like taking a Tesla into the software lab and upgrading its performance through precise coding – not welding on parts from other cars. The plant remains fundamentally itself but better equipped to handle modern challenges.

The greatest advantage for us as producers and consumers of food is that many of the changes that we can make using this ‘Tipp-Ex’ can also be made with conventional breeding. That means that the precision-bred organism poses the same risk to humans, animals, and the environment as a conventional crop. The end result can also be obtained through conventional breeding, but possibly with a much longer time frame, resulting in a higher cost of development.

GMOs are subject to extensive risk assessments to determine any possible risk to the environment, humans, or animals. Tests are conducted to determine changes in invasiveness, allergenicity, and toxicity. While these regulatory checks are needed, complying with the requirements to register a GMO for planting in a country takes extensive resources (10 to 15 years and upwards of $150 million).

So, if these new breeding techniques can deliver a plant variety that has improved traits (e.g., higher yield) in a shorter period and pose the same risk as a conventional crop, we can expect some of the following benefits:

- Quicker turnaround time on varieties will decrease the cost of developing new varieties.

- New varieties will reach producers faster.

- Improved plant varieties will benefit the value chain and that can address global challenges.

So how far are we from planting crops produced using this ‘Tesla’ of plant breeding? For most countries, these tools are becoming a reality very quickly. In the USA and Canada, high-oleic soybean oil has been available to consumers since 2019. In Japan, a gene-edited tomato was commercialised in 2021. Gene-edited maize has been approved in Japan with approval pending in the US, and China approved gene-edited soybean, wheat, maize, and rice in late 2024. In South Africa the situation is very different.

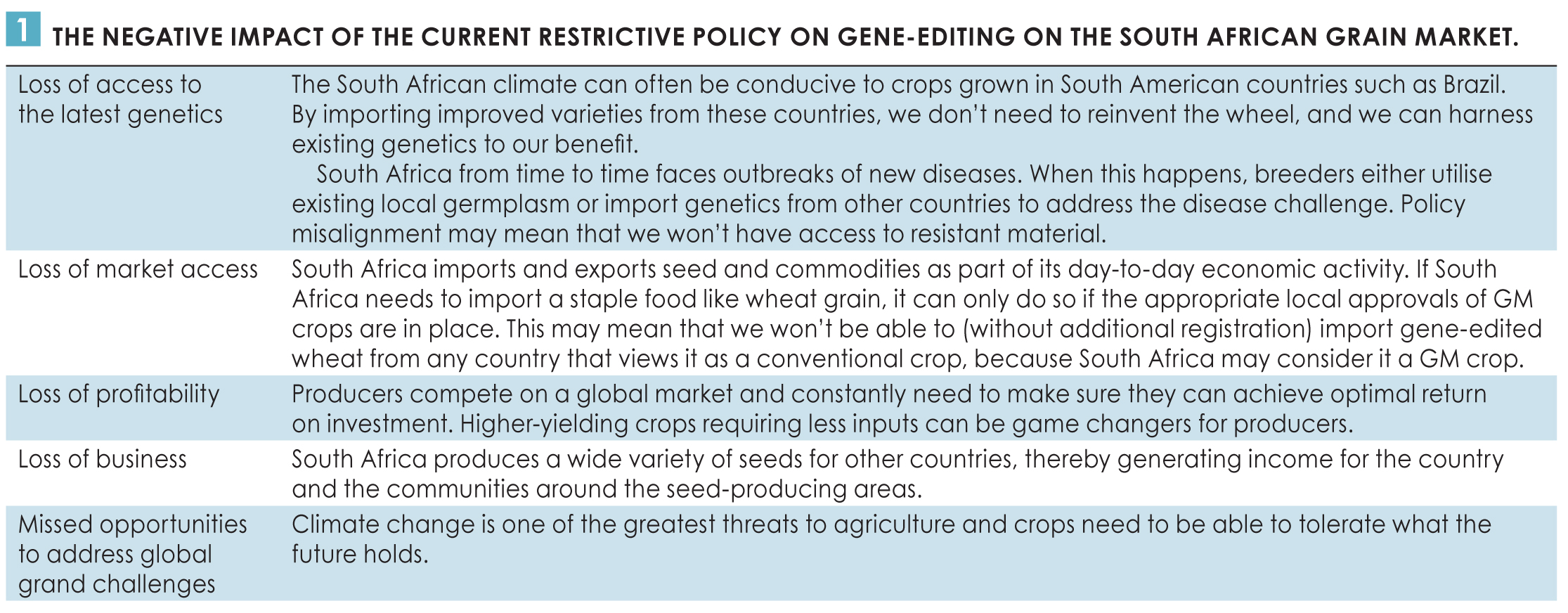

While most countries one by one released documents stating that some gene-edited crops will be considered similar to conventional crops and will be regulated as such, the conversation in South Africa has been different. In 2021, the Department of Agriculture published a public notice that stated ‘the Executive Council has concluded that the risk assessment framework that exists for GMOs would apply to NBTs’. The Executive Council is the regulatory authority advising the Minister of Agriculture on any and all matters related to GMOs.

The global reaction to SA’s stance

The world reacted by labelling South Africa one of a few countries (if not now the only one) that views gene editing through the same lens as GMOs. On global maps, South Africa is frequently seen as a red dot amidst a sea of green (where gene editing can be considered as similar to conventional breeding).

South African breeding programmes frequently use germplasm from international sources, and policy misalignment impacts local access to technology.

Are all policies equal?

No. Various thresholds can be implemented to determine if a crop is similar to a conventional one and can include:

- Absence of foreign DNA

- Scale of change to DNA

- No new or increase in toxins, allergens, and antinutrients

- No compositional changes

- No new food use

- Trait not related to herbicide tolerance

Failure to comply with the above thresholds results in the variety being considered a GMO.

Are all precision-bred crops similar to conventional?

Are all precision-bred crops similar to conventional?

It is often considered that if a change could have been achieved via conventional breeding, then the plant should be considered as a conventional crop (i.e., non-GMO). However, this same technology (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9) can be used to transfer a gene from one organism to another, like with GMOs, and the resulting plant will be and should be considered a GMO.

Should precision-bred crops be subject to national regulations?

Yes. Crop cultivars planted in South Africa are subject to either the Plant Improvement Act or GMO Act for the registration of plant varieties. Irrespective of the approach South Africa follows to gene editing, crops should still conform to the processes and standards as set out in national legislation. Transparency is key to building trust and a common set of rules protects users and consumers.

Is precision breeding the ultimate solution?

No. Like cars, different methods of plant breeding are used depending on the outcome that needs to be achieved. But South Africa is a nation under pressure.

The triple challenges of climate volatility, a growing population, and persistent poverty requires all of our skills to ensure a prosperous and food secure South Africa. In a country where food insecurity affects more than 11 million people and extreme weather events are becoming more frequent, producers need to be able to choose the best possible varieties for their specific circumstances.

By ensuring that plant breeders have access to a variety of tools and germplasm, we aim to develop varieties that are suited to the needs of various producers while protecting human health, animal health, and the environment. Genome editing is not the one and only solution to the challenges we face as a country, but it can make a significant positive contribution.

Genome editing is not just a scientific advancement – there’s also real economic opportunity. South Africa could position itself as a leader in genome editing on the African continent. Just as Tesla positioned itself as a tech-forward leader in a crowded car market, South Africa can do the same in agriculture – exporting not only food, but also intellectual property, research, and technical expertise.

Should all crops be ‘precision-bred’?

Producers need to be able to choose which crops, varieties, machinery, and inputs are best suited for them to support themselves, their families, communities, and the country at large. South Africa is fortunate to be a biodiverse country where field crops, vegetables, ornamentals, and forage and turf crops can be planted on smallholder to commercial scale.

Just like choosing a 4×4 for off-road adventures or a hatchback for parking in Cape Town, different approaches are needed for crop breeding.

Policy frameworks that embrace innovation

A whole-of-society approach is needed to support policy frameworks that embrace innovation for the value chain. Producers of all scale benefit from varieties that are higher yielding, disease resistant and better suited to climate variability. The processing industry benefits from varieties yielding produce of high quality that requires less processing as well as additives and preservatives. Retailers benefit from products with a longer shelf-life and hardiness, reducing packaging and food loss. Ultimately, these benefits translate into more affordable food for consumers and the country’s food and nutritional security.

South Africa cannot afford to sit idle with an agricultural system running on outdated engines. Nor can it rely exclusively on custom machines that are expensive and slow to arrive. Genome editing offers a third way – a local, precise, and sustainable solution to modern agricultural challenges.

Just as the auto industry embraced the electric revolution, South African agriculture must embrace the genomic one. It’s time to trade in the classics and customs for something built for the road ahead. It’s time to invest in the Tesla of crops.