Dry bean is an important grain crop in South Africa produced mainly for consumption due to its high protein content. Major producing areas are the Free State, Mpumalanga and Limpopo provinces. Producers in the North West are beginning to cultivate dry beans, although production remains at a relatively low level. Red speckled beans command the biggest area of production while small white canning beans are produced under contract by some producers (DAFF, 2021).

While dry bean production in the areas mentioned above is primarily conducted at a commercial scale, there is also a niche group of smallholder farmers cultivating this crop, particularly in the Limpopo province. The latter group plant dry beans in the autumn. This is to avoid high summer temperatures combined with high humidity, which can often lead to high infestation of various leaf and pod diseases such as angular leaf spot and rust. Therefore, planting in autumn when temperatures are getting lower makes these areas unique with regards to dry bean production.

Another advantage is that dry bean is an early maturing crop, reaching maturity before incidences of frost, which is also not that prevalent in these areas. These production areas include Tshiombo in the Vhembe district, Maruleng and Giyani in the Mopani district, and Mafefe in the Capricorn district. In these regions, farmers rely on supplementary irrigation, as critical stages of dry bean development, such as flowering and podding, coincide with the decline or complete cessation of seasonal rainfall. However, production in these areas still faces several constraints.

Many farmers rely on recycled seed of poor quality for planting, while others purchase ‘seed’ of unknown origin from supermarkets. In most cases, these are grains intended for animal consumption rather than certified seed. As a result, germination and emergence rates are often poor, leading to weak plant stands and significantly reduced yields. This challenge presents an opportunity to evaluate alternative cultivars at the local level for their yield potential. However, selecting a good cultivar alone is not sufficient to ensure high yields. Other agronomic factors, such as soil fertility, also play a critical role (Sebetha and Islam, 2021).

The majority of smallholder farmers apply fertiliser without knowledge of the soil nutrient status. No concerted efforts are made in these production areas to take soil samples and have them analysed so that fertiliser recommendations can be made. Lack of this important information with regard to soil nutrient status implies that farmers either over- or under apply fertiliser for dry bean production. In some cases, farmers apply the wrong fertiliser product due to lack of knowledge. For instance, most farmers at Tshiombo location normally apply a mixture fertiliser as topdressing, e.g., 3:2:1 (25), while no fertiliser is applied at planting. This phenomenon also necessitated the need to investigate the levels of fertilisation to establish the best level for the best yield. This information is important so that farmers can start to use fertiliser judiciously. Therefore, an experiment was conducted in two of these production areas (Tshiombo and Maruleng) over two seasons (2023/2024 and 2024/2025) to investigate the effects of cultivar and fertilisation level on dry bean yield.

Methodology

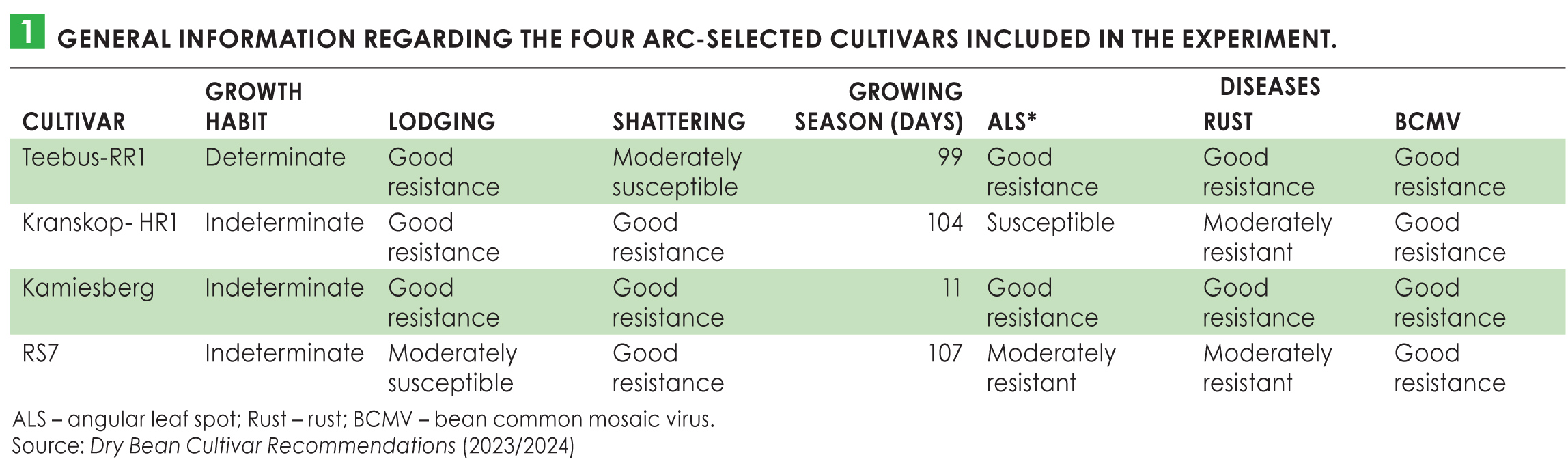

Research trials were conducted during the 2023/2024 and 2024/2025 dry bean growing seasons. Four cultivars bred at the ARC-Grain Crops were selected for the experiment (see Table 1). These included three red speckled dry bean cultivars (Kamiesberg as V1, RS7 as V2, Kranskop HR1 as V4) and one small white canning dry bean (Teebus RR1 as V4).

Three levels of fertilisation were included in the experiment based on the yield target. These were fertilisation levels to achieve 1,5 t/ha as level A; 2 t/ha as level B; and 2,5 t/ha as level C. At both locations, soil samples were taken before the start of the trial to determine the nutrient status of the soil. Soil analyses included nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na) and pH. Soil clay percentage was also determined. The clay percentage of the topsoil was 26 and 15 at Tshiombo and Maruleng respectively. As such, all three fertiliser levels in the trials were based on the soil analysis results. Each cultivar was assigned to all the fertiliser levels, resulting in twelve treatment combinations.

Three levels of fertilisation were included in the experiment based on the yield target. These were fertilisation levels to achieve 1,5 t/ha as level A; 2 t/ha as level B; and 2,5 t/ha as level C. At both locations, soil samples were taken before the start of the trial to determine the nutrient status of the soil. Soil analyses included nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na) and pH. Soil clay percentage was also determined. The clay percentage of the topsoil was 26 and 15 at Tshiombo and Maruleng respectively. As such, all three fertiliser levels in the trials were based on the soil analysis results. Each cultivar was assigned to all the fertiliser levels, resulting in twelve treatment combinations.

Planting was done on 11 and 12 March 2025 at Tshiombo and Maruleng respectively. 3:2:1 (25) fertiliser was applied at planting and LAN (28) applied as topdressing four weeks after emergence. A pre-emergent herbicide (Dual Gold) was applied to control weeds immediately after planting to give the crop an early competitive advantage. The trials were monitored during the growing season for diseases and pests. Weeds that developed later during the growing season were hand-hoed by participating farmers in the respective localities.

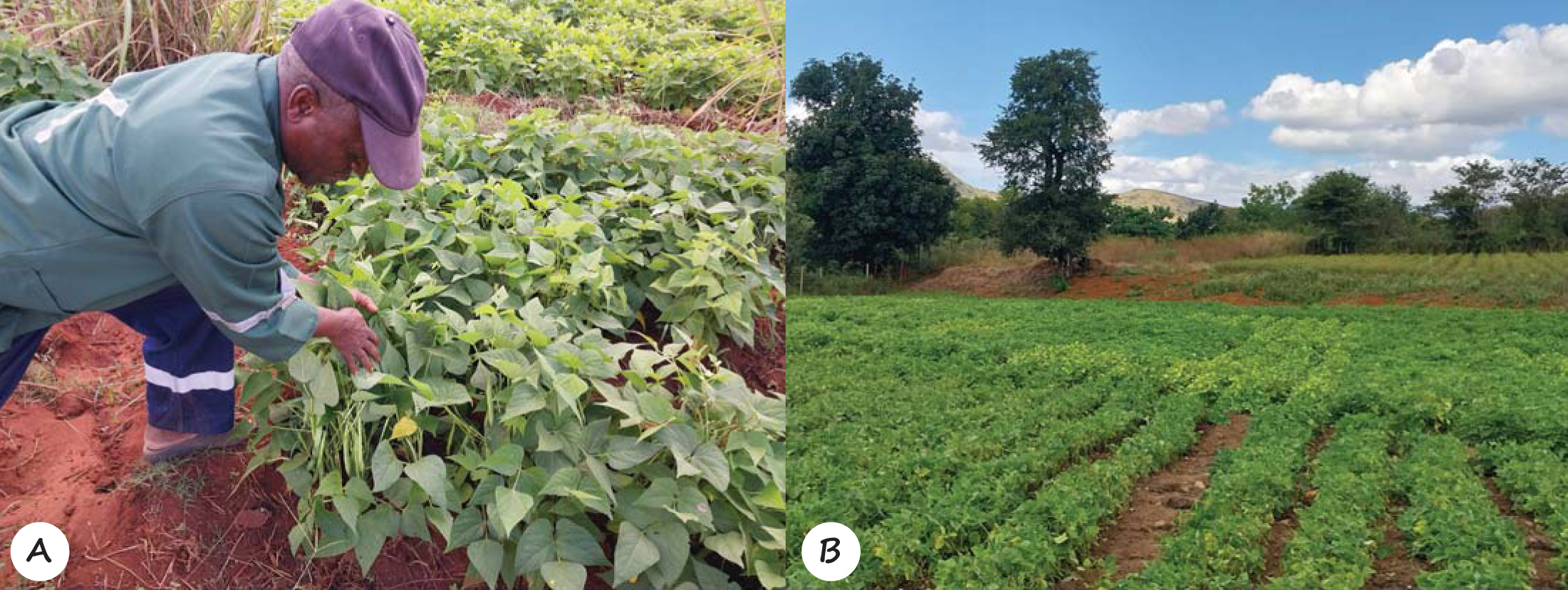

Farmers’ days were also held at both locations in both seasons (Figure 2) to serve as a platform for dry bean producers and other relevant stakeholders in the respective areas to observe and discuss performance of cultivars and other agronomic-related aspects regarding dry beans as well as the effect of different fertilisation levels. Both trials were harvested at physiological maturity to determine both the biomass and grain yield.

Results

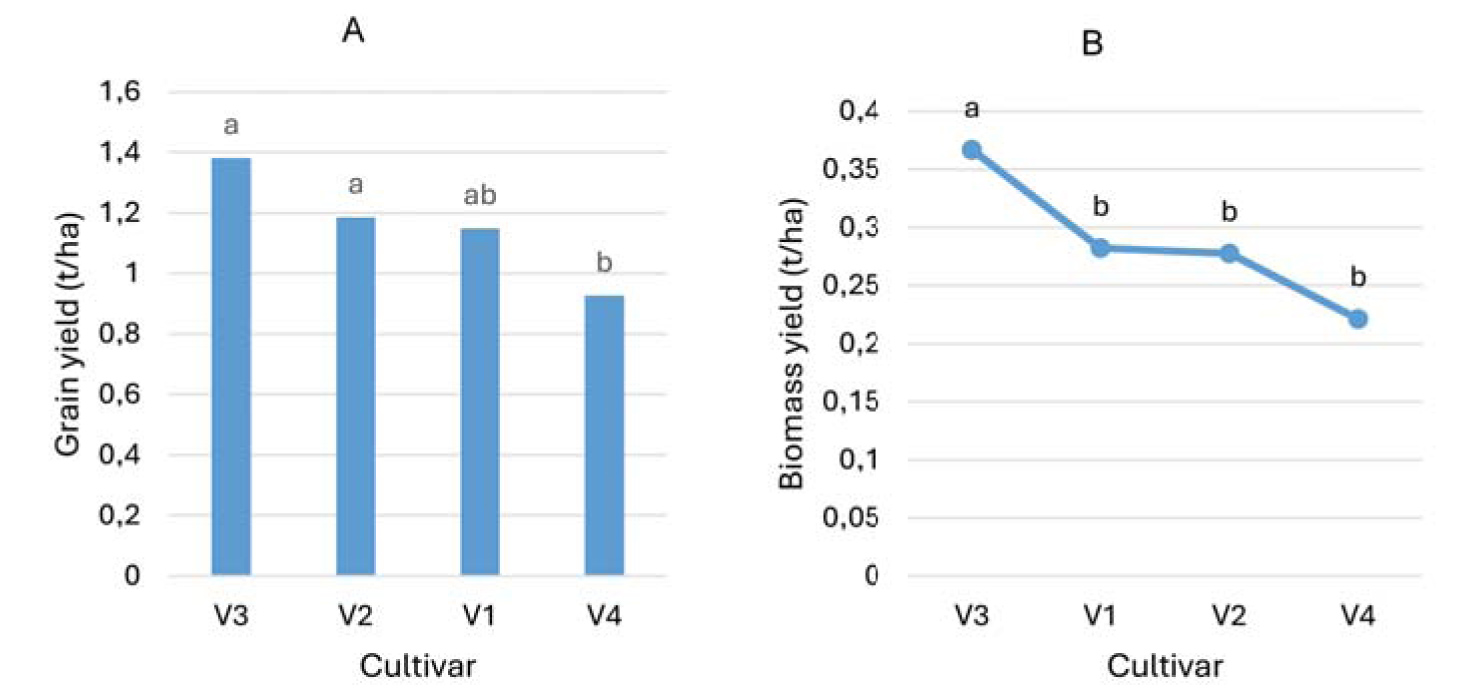

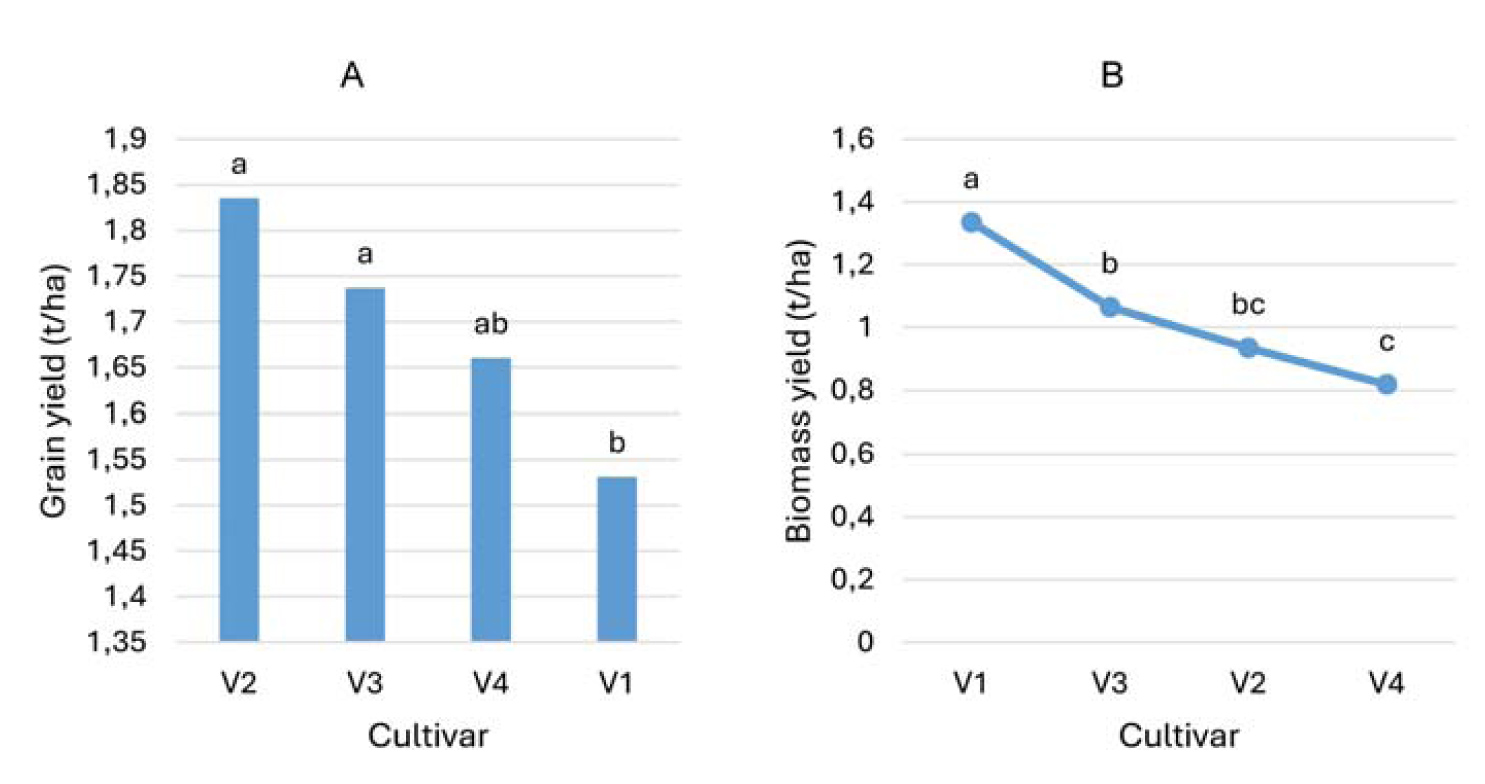

The main factors, cultivar and fertilisation, did not have any effect on grain and biomass yield at Tshiombo in the 2023/2024 season (data not shown). In the 2024/2025 season, only cultivar had a significant effect on both grain (P=0,007) and biomass (P=0,002) yield (Graph 1A & 1B). During this season, both Kranskop-HR1 and RS7 showed an increase in grain yield compared to Teebus-RR1 that gave a lower yield (Figure 1A). Kranskop-HR1 also showed improved biomass yield, while no differences in biomass yield were observed for the other three cultivars (Figure 1B).

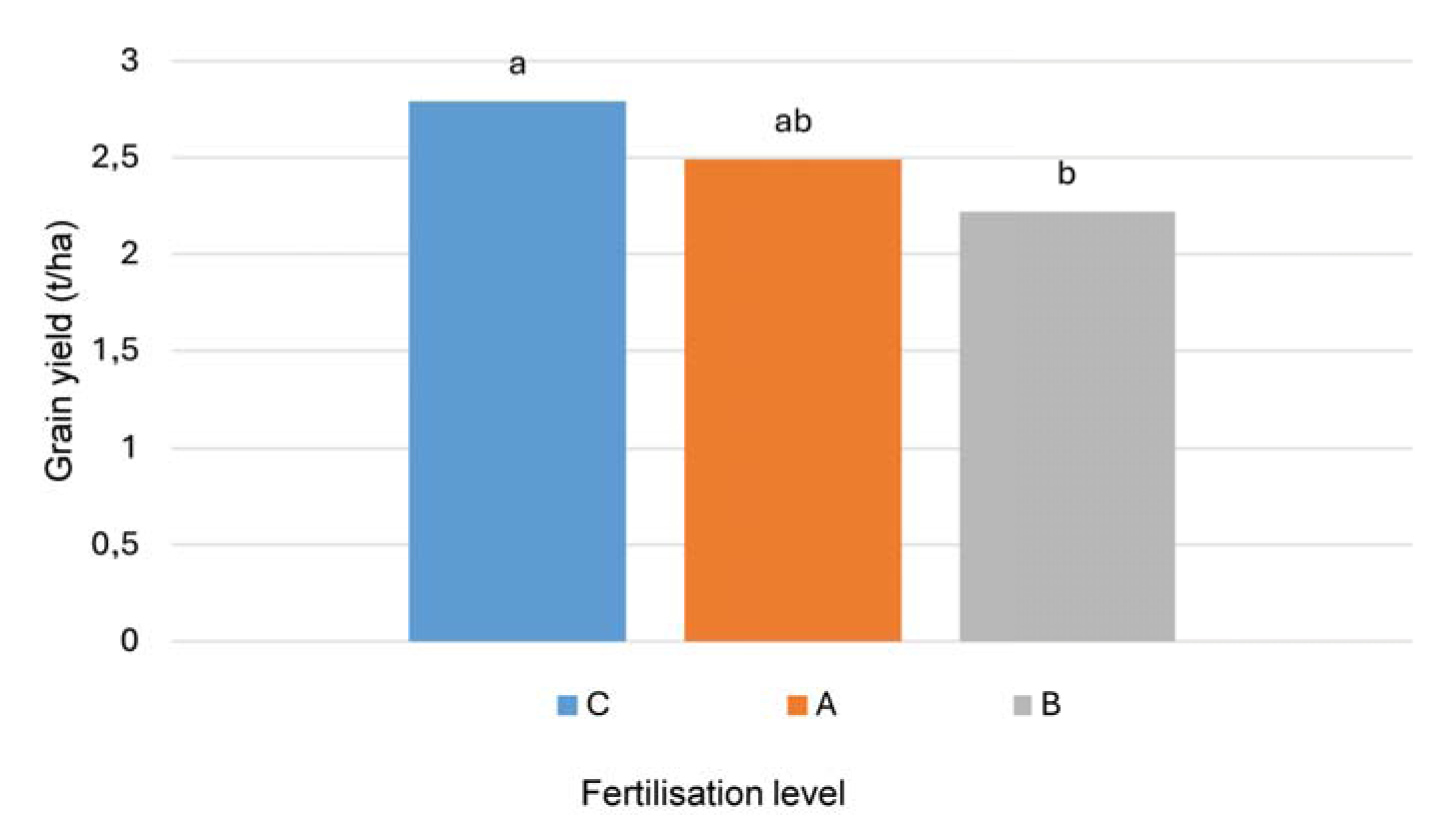

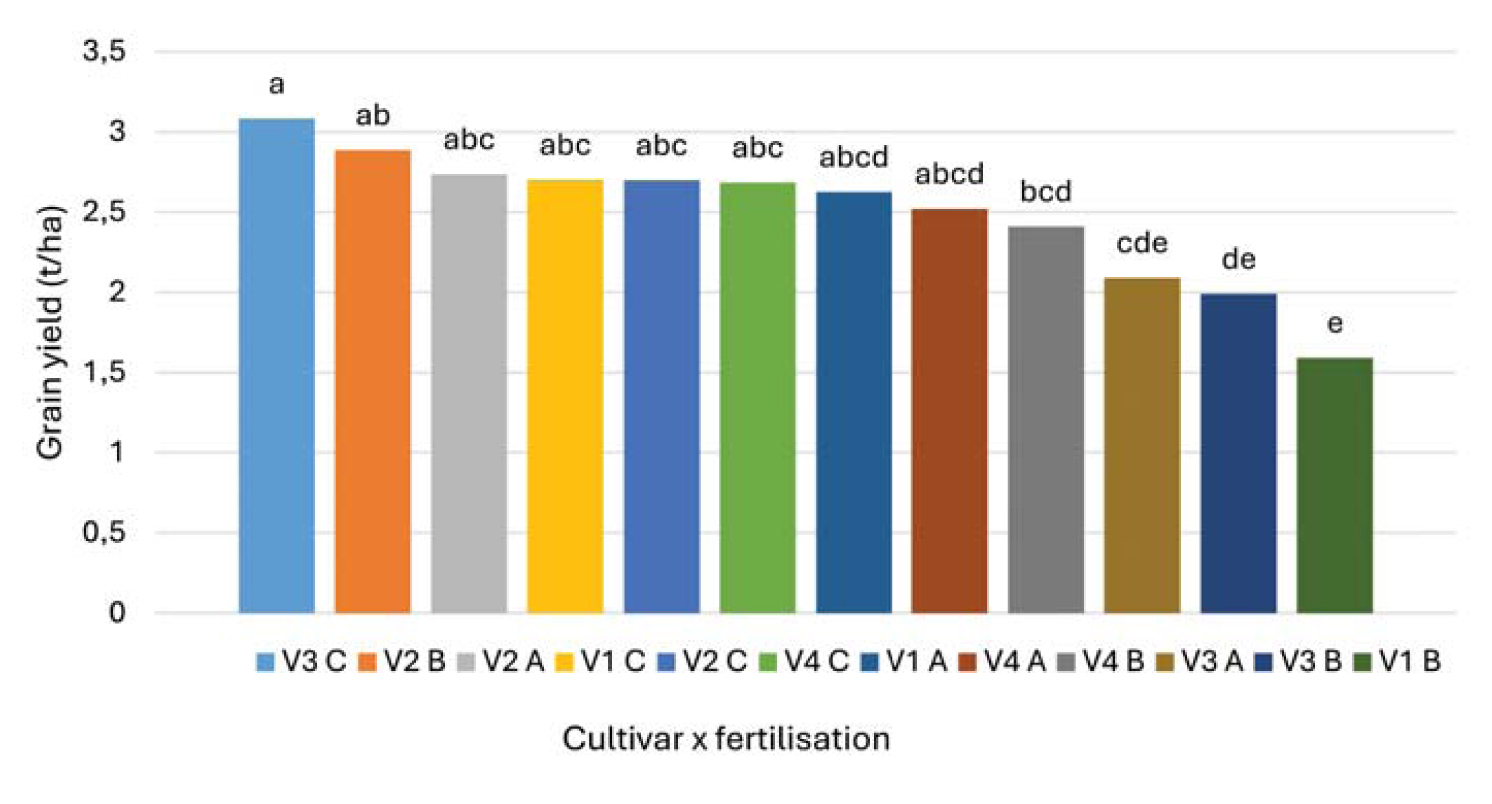

A different outcome was observed at the Maruleng site in the 2023/2024 season, with the effects of fertilisation giving significant differences (P=0,006) in grain yield (Graph 2). The highest fertilisation level increased grain yield as compared to the other fertilisation levels. The lowest yield was observed under medium fertilisation. In this season and site, the combination of cultivar and fertilisation also had an influence on grain yield (P=0,02, Graph 3). The highest yield was observed when Kranskop-HR1 was combined with the highest fertilisation. Kamiesberg combined with medium fertilisation gave the lowest yield. In the 2024/2025 season at Maruleng (Graph 4A), both RS7 and Kranskop-HR1 led to higher grain yield (P=0,01), while Teebus-RR1 showed a reduction in yield compared to other cultivars. In this season and locality, Kamiesberg produced higher biomass yield (P<0,001) while Teebus-RR1 produced lower biomass yield, corresponding to the grain yield results (Graph 4B).

Conclusions

Based on the results of both grain and biomass yield at both localities, fertilisation level alone generally did not have an impact except at Maruleng in the first season. This observation is important because these smallholder farmers do not always have the means to buy more fertiliser. Another important aspect is that these farmers should use fertiliser judicially based on soil analysis reports and good recommendations. While the combination of cultivar and fertilisation only affected grain yield at Maruleng in the first season, it looks like Kranskop-HR1 can produce higher yield at higher fertilisation levels at this location. However, this is not consistent and should be considered carefully.

Further investigations are necessary to observe the best combination of fertilisation and cultivar which can produce a better yield. Generally, cultivar had a significant effect on yields of both grain and biomass. This implies that farmers should choose cultivars that are performing better in their localities based on research. Kamiesberg and Kranskop-HR1 performed better with regard to biomass production while RS7 and Kranskop-HR1 produced higher grain yield. Based on these results, Kranskop-HR1 can offer good production of both grain and biomass yield. This is important for farmers who also want to use dry bean residue to feed their livestock. High biomass production is also important for nutrient cycling and soil organic matter.

For further information, contact Dr E Nemadodzi at Nemadodzie@arc.agric.za.

References

References

Department of Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries, 2021. A profile of the South African dry bean market value chain.

Sebetha, ET & Islam, BM. 2021. Growth Performance of Three Dry Bean Cultivars Affected by Different Rates of Phosphorus Fertiliser and Locations, Asian Journal of Plant Sciences.