How many South Africans can identify sorghum in their everyday meals? For most modern households, the answer is likely ‘very few’. Despite being one of the most drought-tolerant and versatile crops in the country, sorghum has yet to become a staple in South African diets. Its presence in retail stores, in the local markets, and on restaurant menus is limited, leaving consumers largely unaware of its nutritional value outside of its cultural relevance; commonly known as umqombothi or traditional beer indigenous to the Sotho and the Nguni culture.

This lack of visibility has contributed to stagnant demand, discouraging producers from planting it and limiting the growth and development of the industry. This is not to say that there is no market for the sorghum that is currently produced, as the output is processed for industrial uses such as malting and brewing. This article explores the market conditions and initiatives to highlight reasons why sorghum deserves better recognition.

Sorghum production trends

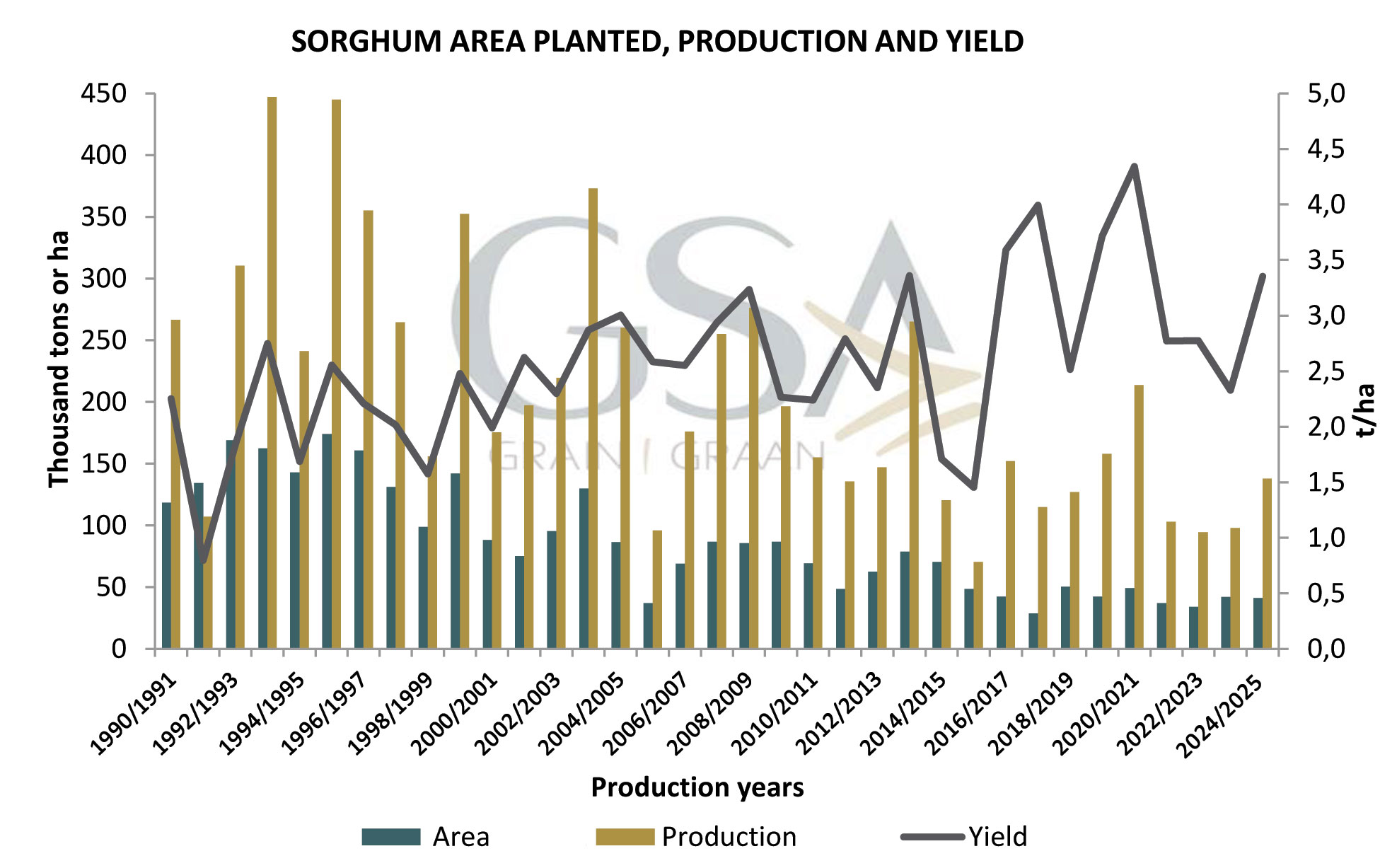

Sorghum has long been recognised as one of the most drought-tolerant crops in South Africa, yet its role in the grain industry has steadily decreased over the past three decades. Since the mid-1990s, both the area planted and total production of sorghum have declined while yields have improved due to improved cultivars and investment in technology (see Graph 1). Experts argue that this decline was due to an increase in the demand and production of maize. The sixth production forecast by the Crop Estimates Committee (CEC) reported that sorghum production in the 2024/2025 season was estimated at just 98 000 tons, with projections for 2025/2026 showing an increase to 135 670 tons. Despite the improved yield levels, producers continue to allocate fewer hectares to sorghum, signalling a lack of market confidence in the crop’s profitability.

It is important to highlight that the drought-tolerant trait is supported by the increase in the area planted from the 2022/2023 to the 2023/2024 production season, where other crops suffered production area losses during the drought season. Area planted is forecasted to decrease by 950 ha in the 2025/2026 production season; however, production is forecasted to increase by 39 970 tons.

The Free State is South Africa’s leading producer of sorghum, followed by Mpumalanga and Limpopo. The total supply for the 2025/2026 season is estimated to be 236 317 tons, with 43 680 tons being processed mostly for floor malting and meal, rice, and grits. Demand is also projected to decrease to 156 630 tons while it is currently estimated to be 164 279 for the current season.

Price analysis and trends

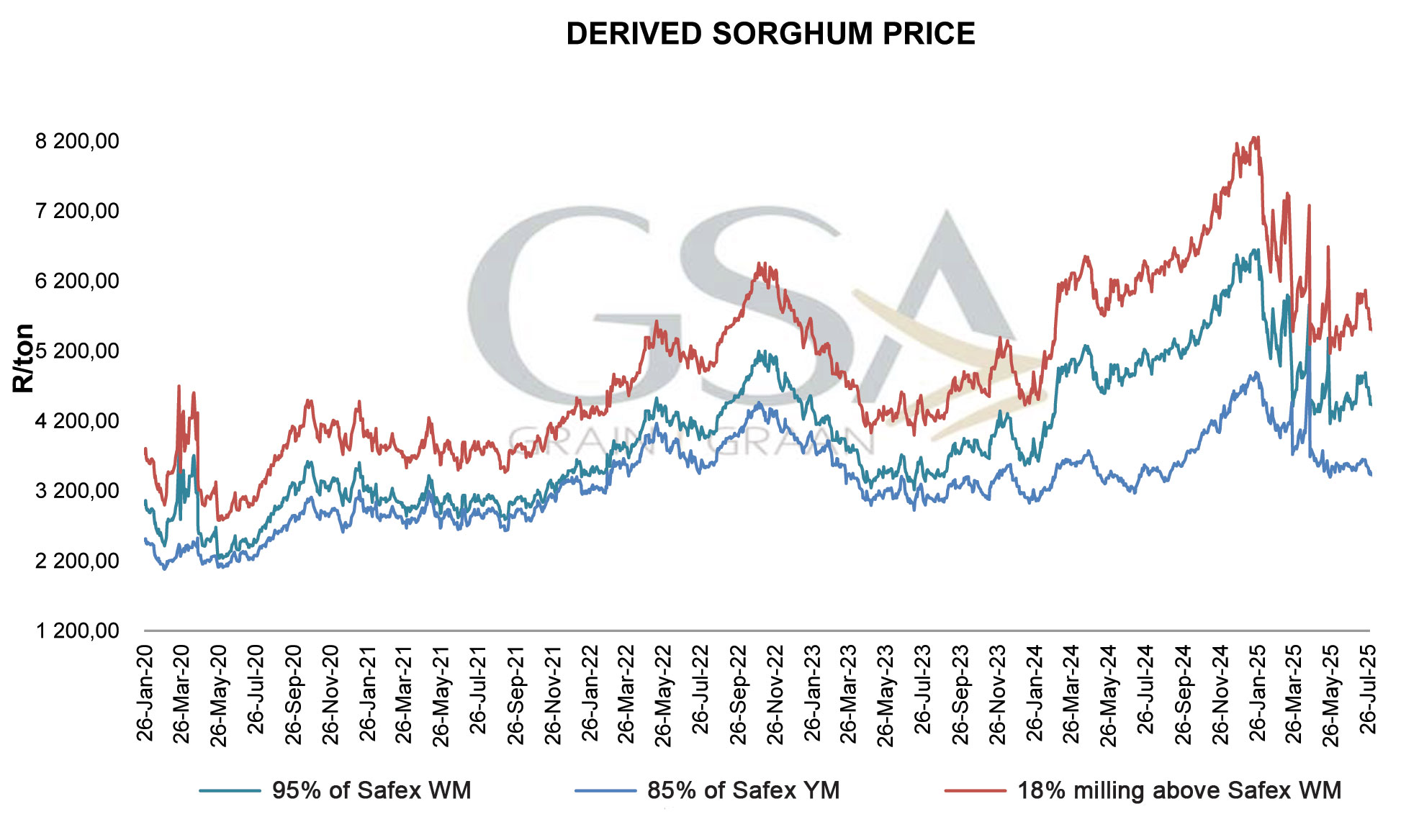

The challenges faced by the industry are reflected in the pricing of the crop. Sweet sorghum is not traded on Safex, so daily derived prices are calculated and published by Grain SA to improve transparency. These are benchmarked against maize. In periods of large supply, the sorghum price tends to move towards export parity and often aligns with 95% of Safex white maize. When sorghum begins to compete with the animal feed market, it trades closer to 85% of Safex yellow maize. The upper ceiling is considered 18% milling above Safex white maize, because sorghum provides roughly 18% more meal compared to maize when milled. As shown in Graph 2, derived sweet sorghum prices between November 2024 and March 2025 reached their highest levels in years due to tight white and yellow maize supplies as a result of the delayed rains in the previous season, underlining the extent to which sorghum pricing depends on maize market dynamics.

Trade environment

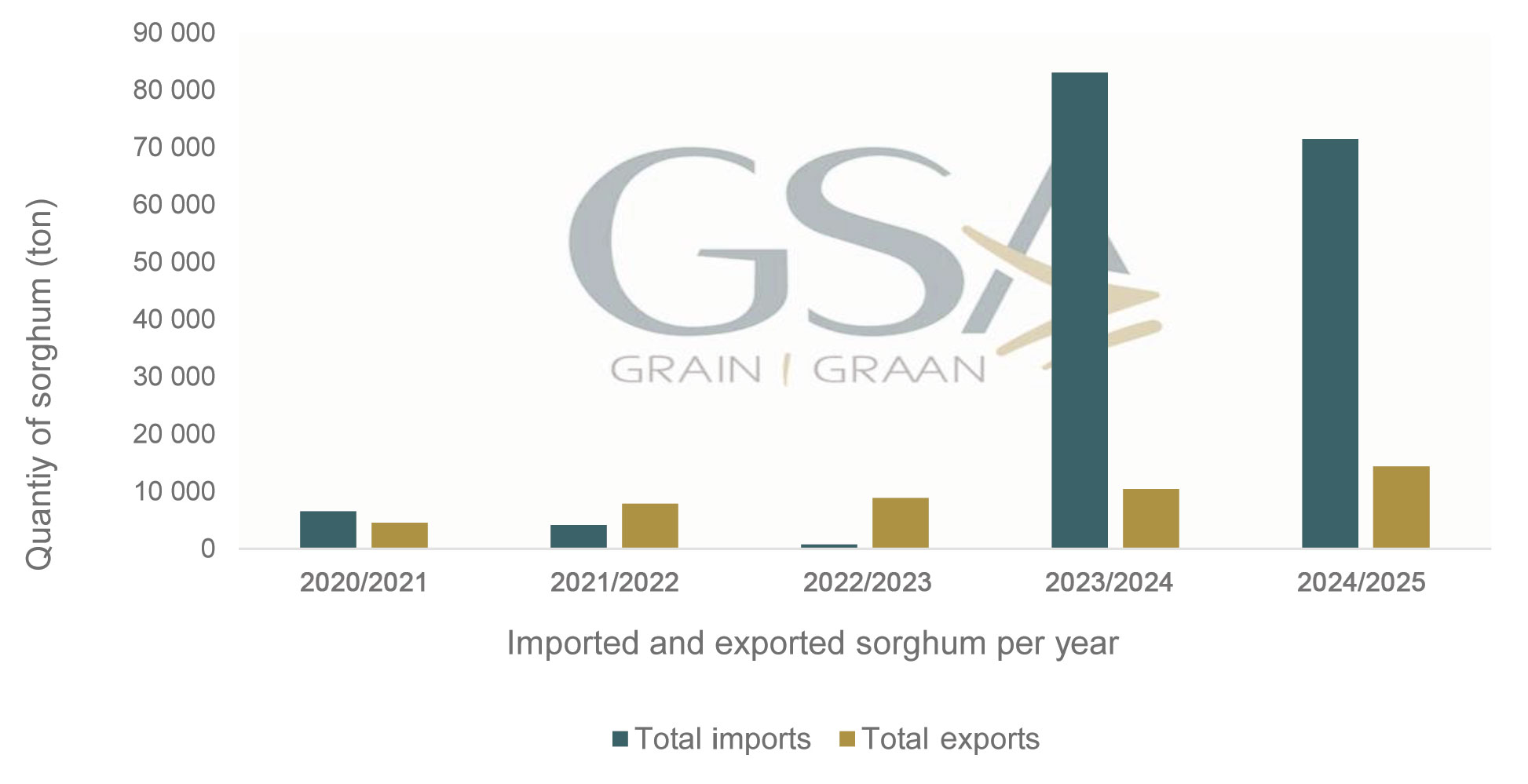

Over the past two years, sorghum imports into South Africa have averaged 73 437 tons annually. Since March 2025 alone, the country has imported 71 466 tons, representing 44% of total sorghum procurement to date. In comparison, during the 2023/2024 production season, imports accounted for roughly 50% of the total domestic supply. With four months remaining in the current season

(November 2025 to February 2026), there are growing concerns about the profitability of local sorghum production.

According to Graph 4, 71 405 tons of sweet sorghum and 61 tons of bitter sorghum were imported. Locally, South African producers produced 59 502 tons of sweet sorghum and approximately 29 919 tons of bitter sorghum, bringing total domestic production to 89 421 tons. The relative increase in bitter sorghum production may be linked to quelea bird infestations affecting sweet sorghum yields, highlighting the ongoing need for effective pest management strategies.

Exports are also on the rise, though primarily to neighbouring countries. For example, Botswana imported 13 728 tons of South African sorghum in 2024/2025, largely due to a poor production year caused by extreme heat conditions. Despite this growth, exports remain small compared to imports, underscoring structural weaknesses in the South African sorghum industry. Sorghum imports for the current season reached 99 146 tons, accounting for roughly 40% of the country’s total supply. The National Agricultural Marketing Council (NAMC) forecasts 10 000 tons of imports for the 2025/2026 season.

Imported sorghum quality

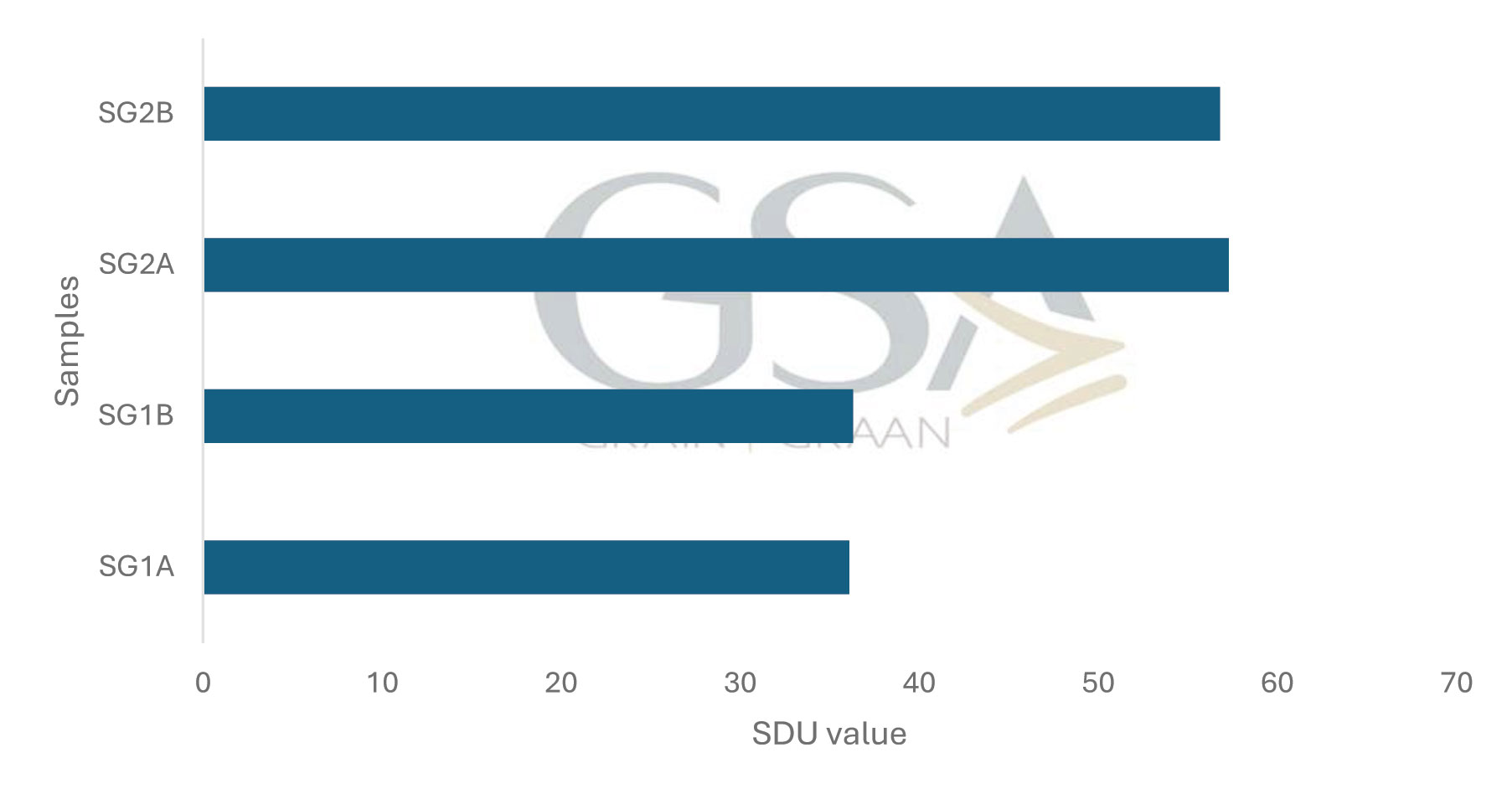

Research into sorghum’s malting characteristics further demonstrates its industrial potential. Two samples (one imported and one local sample) were tested for SDU values, which measure enzyme strength for converting starch into sugar during brewing:

- Sample SG1 (imported): 66% germination, SDU below 40, had poor malting potential.

- Sample SG2 (local): 92% germination, SDU above 50, was suitable for quality malt.

The above results indicate that the research supports the increase in local sorghum production and less dependency on imports; however, the biggest issue remains creating a local demand-pull.

Sorghum Cluster Initiative

The Sorghum Cluster Initiative (SCI) was established by the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI). A study was initiated and funded to establish market opportunities for sorghum in South Africa. Key measures include the following:

- A proposal to remove VAT from sorghum products to improve competitiveness.

- A national awareness campaign highlighting sorghum’s health and heritage value.

- A pre-breeding programme to develop high-performing hybrids suited to local conditions.

- Collaborative trials between universities and private partners that are producing promising results.

- Innovative quelea control methods, including drones and natural repellents, to protect crops.

- Market analysis mapping the value chain and assessing competitiveness.

- Plans for an agro-processing facility, although funding constraints have delayed implementation.

Conclusion

Sorghum is a crop that deserves better recognition, both in households and across the broader agricultural economy. The biggest challenge remains creating greater demand and increasing the consumption of the crop. This has become the main focus of the Grain SA Sorghum Working Group, which is coordinating efforts across research, policy, and market development to ensure that sorghum reaches its full potential in both the domestic and international markets.