Maize remains a cornerstone of global agriculture, yet its production continues to be threatened by ear rots that compromise both yield and grain quality. The 2024/2025 season proved especially challenging due to excessive rainfall, which created ideal conditions for the development of three economically significant ear rots: Stenocarpella maydis (Diplodia), Fusarium graminearum (Gibberella or pink rot) and Fusarium verticillioides (Fusarium ear rot).

A notable increase in producer enquiries has been observed, particularly concerning S. maydis infections following late-season rains during the 2024/2025 planting season. These infections often go unnoticed because it shows no visible symptoms – a phenomenon referred to as skelm Diplodia. This can lead to an unexpected downgrading of grain quality upon delivery.

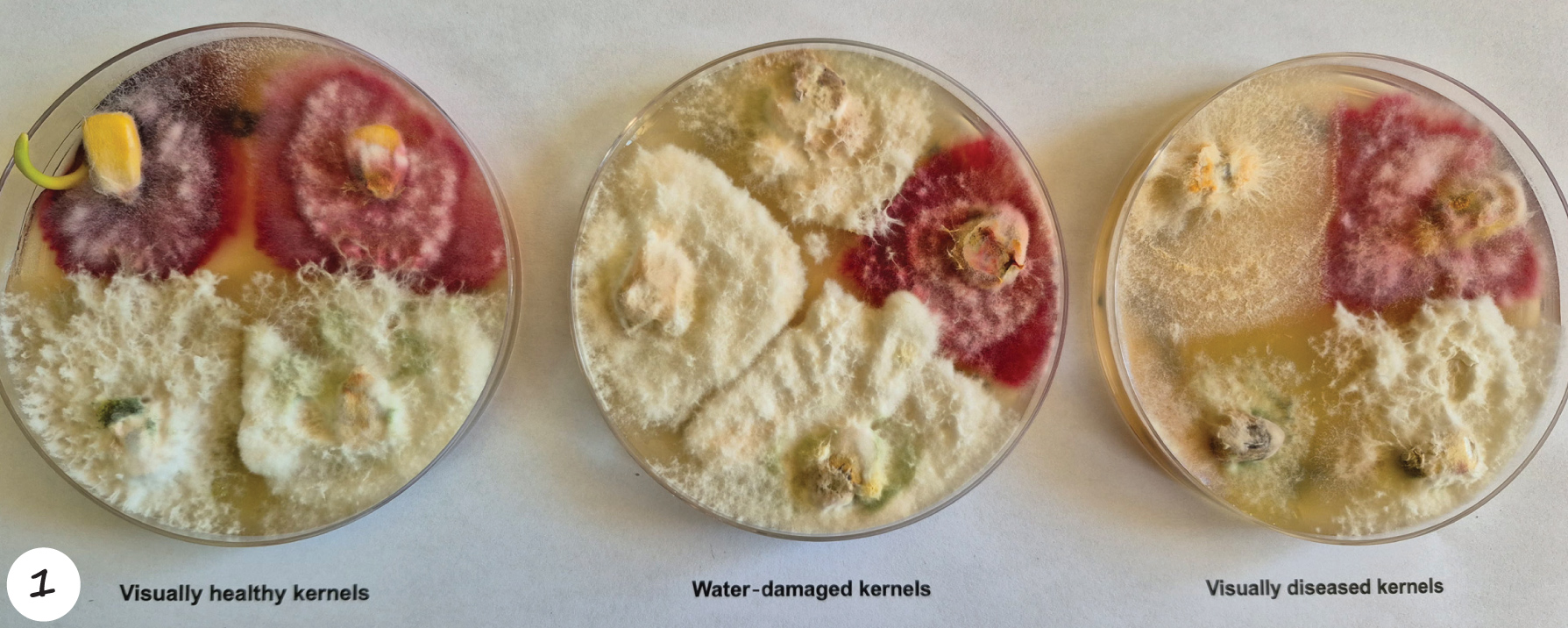

In one such case, a sample submitted to our laboratory revealed infections of both S. maydis and F. graminearum in visually healthy kernels as well as in those showing water damage and visible disease symptoms (Photo 1). However, it is important to note that water-damaged kernels and symptomless kernels do not always harbour fungal infections. Therefore, submitting a sample to a plant pathologist for accurate assessment is essential to determine the presence of any disease. Typically, infected kernels are lighter in weight and may exhibit white streaks or other forms of discolouration.

These fungal pathogens not only damage maize ears, but also produce harmful mycotoxins, which can pose serious health risks to humans and animals. While cultivar resistance plays a key role in managing these diseases, complete resistance is rare and trade-offs with yield potential often complicate cultivar selection. A project funded by the Agricultural Research Council (ARC) and the Department of Agriculture, is actively monitoring the prevalence of these ear rots and their associated mycotoxins in both commercial and smallholder fields. This article aims to provide producers with insights into the biology and impact of these pathogens, share findings from the recent season, and offer practical, science-based management strategies to reduce losses and safeguard food safety.

Fusarium ear rot (Fusarium verticillioides)

Economic importance: F. verticillioides are found worldwide and are mostly isolated from maize kernels. Producers suffer millions of rands in losses annually due to poor seed quality and reduced yields. The fungus produces a mycotoxin called fumonisin. Grain traders incur costs to test for fumonisins, which are passed on to consumers through higher product prices. Current grading regulations rely on visual symptoms, but F. verticillioides can infect maize without producing visible signs. Some isolates produce more fumonisins than others.

Occurrence and spread: The fungus is widespread in South Africa, especially in hot, dry regions with temperatures rising above 28 °C. Stress factors like insect and bird damage as well as drought conditions promote its spread. Infection by this fungus can occur at any growth stage and it is often seedborne. It can also infect roots from the soil to grow through the stem to the ear. The fungus overwinters on plant debris and reinfects during the next season. Rain and wind can carry spores to the maize silk, which leads to infection. This fungus possesses multiple infection cycles, which means that plants can be infected several times throughout one growing season.

Symptoms: Typical symptoms include white-pink fungal growth (Photo 2) on kernels near stalk borer damage. Similar symptoms are seen with insect and bird damage. Unaffected kernels may show pink discolouration or white streaks. The fungus can also infect kernels with no visible symptoms, causing producers to be unaware of contamination.

Gibberella ear rot (Fusarium graminearum species complex)

Economic importance: Gibberella ear and stalk rot are widespread in South Africa’s maize production areas. These diseases are caused by 5 of the 13 fungus species in the F. graminearum complex. Research shows that F. boothii and F. graminearum s.s. are responsible for ear rot, especially where maize is rotated with wheat. The other species can affect roots, crowns and stems. Hosts for these fungi include maize, sorghum, wheat, oats, rye, and barley. Gibberella ear rot occurs during warm, wet conditions from flowering to three weeks after silk emergence and is commonly found under irrigation. It is becoming more prevalent in western production areas and where crop residues are retained. The disease causes yield losses and affects grain quality.

Occurrence and spread: The primary source of inoculum is from infected crop residue left in the field the previous planting season. The fungus forms structures on stubble that release spores into the air. Released spores land on silks and behind leaf sheaths or infect roots and crowns. It causes a range of diseases, including ear, stalk, crown, and root rot.

Symptoms: Symptoms include a dark red discolouration (Photo 3) of the ear that can be partial or complete. Early infections can rot the entire ear, with only husks sticking to the ear. Infection starts at the tip of the ear and moves downward. Infected grains are downgraded due to poor quality. The fungus also causes stalk rot that weakens the stem and promotes lodging. Leaf diseases can exacerbate stalk rot when the plant is forced to draw nutrients from the stem in the absence of fully functional, healthy leaves.

Diplodia ear rot (Stenocarpella maydis)

Economic importance: Diplodia ear rot is caused by Stenocarpella maydis and can significantly reduce grain quality, especially during seasons when maize prices are low. The fungus produces diplodiatoxin, which is harmful to cattle, sheep, and poultry. Animals may become paralysed or die. Pregnant ewes that feed on infected ears may give birth to paralysed or stillborn lambs without showing symptoms themselves. Although such instances were mostly reported in South Africa, cases have also been reported in Australia, Argentina, and Brazil.

Occurrence and spread: Epidemics occur in seasons with early drought followed by late rain in the presence of high inoculum levels on surface stubble. The fungus survives on maize stubble and releases spores during spring rains. The spores then infect ears from the base upwards.

Symptoms: Early symptoms include yellowing and drying of infected husk leaves. Rot starts at the base and spreads upward exhibiting white fungal growth with black spore-producing structures visible in the cob tissue (Photo 4). Infected kernels are lighter and often blown out by the harvester. This helps to avoid poor grading. Late infections may be symptomless. Known as skelm Diplodia, it catches producers unaware at delivery when grain is downgraded.

Impact of Fusarium mycotoxins

Ear rots not only reduce yield and quality but also introduce mycotoxins that may be harmful to humans and animals. F. verticillioides produces fumonisins, which may cause softening of the brain and death in horses, lung fluid and liver damage in pigs and are linked to oesophageal cancer in humans from South Africa, Italy, and Iran. The WHO classifies fumonisins as Group 2B carcinogens – possibly carcinogenic to humans. South African regulations now limit fumonisin and deoxynivalenol levels in maize grain and flour.

The F. graminearum complex produces mycotoxins like DON, NIV, and ZEA. DON and NIV inhibit protein synthesis and can cause anaemia, skin lesions, vomiting, diarrhoea, and liver damage. ZEA negatively affects animal fertility.

Although studies on the effects of diplodiatoxin is limited, it is known to be a neuromycotoxin.

Management strategies

Management practices are crucial and alternative control measures are essential in no-till systems. No cultivar offers complete resistance to ear rot pathogens or their mycotoxins. However, cultivar susceptibility varies, and producers should consult seed companies to obtain more resistant options. Research is ongoing to identify resistance traits. Bt maize reduces F. verticillioides infection and fumonisin production. If a cultivar is resistant to Gibberella ear rot, it is not guaranteed to have resistance to stalk rot. Therefore, a package approach is needed.

Diversifying resistance can be achieved through spatial diversity between regions and fields by planting multi-line cultivars and avoiding monoculture. Crop rotation with non-grass crops reduces inoculum while rotation with grass crops like wheat or barley should be avoided. Disease risks are further lowered by reducing stubble through grazing, ploughing, or burning.

Seed treatment helps prevent early infection. Commercial seeds are pre-treated with up to four active ingredients that provide protection to seedlings for the first four weeks. Plant stress and damage during operations and harvest should be avoided. Contamination can be prevented if the grain is stored in clean, dry areas.

Fungicides are economically not viable for ear rot control. Fungi causing ear rots typically infect maize during flowering and grain fill through the silks or via systemic infection from the stalk. During this stage, the timing of fungicide applications is difficult and fungicides may not reach the infection site effectively. Once the fungus is inside the ear, chemical treatments cannot penetrate the husk and kernels to eliminate the pathogen. An integrated management system, focusing on cultivar choice, rotation, and residue management is recommended.

For more information, please contact Dr Belinda Janse van Rensburg at 018 299 6357.