senior lecturer, Depart-ment of Plant and Soil Science, FABI, University of Pretoria

Dr Robert Mangani,

lecturer in agronomy, Department of Plant

and Soil Science, FABI, University of Pretoria

Climate change due to increased carbon dioxide and greenhouse gases was first described in the Charney report of 1979. This first report sparked much debate, research, and political rivalry over the last 46 years and this has blurred the general public’s understanding of the topic. While there is much debate about the root cause of this change, the one thing that most can agree on, is that the climate is changing and these changes are threatening crop production.

There are different aspects to these changes: (1) The underlying change is a slow, but consistent increase in the average global temperature. (2) This small but steady warming brings with it an increase in the duration, severity, and frequency of extreme weather events, including flooding, heat waves, and droughts.

These signatures of change are not always easy to observe in South Africa due to the high seasonal variability we naturally have, but in more stable climates across Europe these signatures are undeniable. Nevertheless, South African producers who collect their yearly on-farm weather data are starting to recognise shifts in rainfall distribution and increases in high-heat days on their farms. However, there have not been many published studies on the district level changes that can already be observed and how these changes might be extrapolated into the future given current climate change models.

Future climate-change modelling is a growing field of study, and each year brings with it more sophisticated models and better predictions. These predictions are essentially the best guess given the current data and technology, which means they are subject to change as new data and new technologies emerge. In general climate scientists always model at least two scenarios: One is usually a ‘business as usual/worst case’ scenario (e.g., RCP 8,5) where nothing can be or is done to limit CO2 and greenhouse gas emissions, and a ‘moderate’ scenario (e.g., RCP 4,5) where strategies to limit CO2 and greenhouse gases are working to curb climate change. They are not a crystal ball to be taken as fact, but rather tools to help with understanding the potential climate risks in the future.

It is important to highlight that climate scientists and producers are working at very different time scales, where climate predictions often run 50 to 100 years into the future with a goal to understand how we secure crop production for our grandchildren and their children. Producers, however, need to be focused on the coming season to ensure the crop is in the ground, developing appropriately and is healthy, and the subtle changes we are observing in our crop growing districts are already impacting crop production. Just seven short years ago we were facing day zero in Cape Town and one of the most severe droughts in South Africa (climate change drives more extreme weather events; Archer et al., 2019). The last few cooler and much wetter summers have improved maize yields but are driving devastating Sclerotinia head rot outbreaks across sunflower production areas (climate change shifts pest and disease distributions; Wójtowicz and Wójtowicz, 2023).

Our studies aimed to understand what climate shifts have already occurred over the last 30 years in six major maize-growing regions (Mangani et al., 2025) and given what we know of these climatic shifts and maize crop development how these changes might affect maize growth as climate change progresses (Mangani et al. 2023).

Study information

Study 1: Climate data from the Agricultural Research Council – Institute of Soil, Climate, and Water (ARC-ISCW) and the South African Weather Services (SAWS) were obtained from 1986 to 2016 for six districts (Klerksdorp, Schweizer-Reneke, Lydenburg, Standerton, Bethlehem, and Bloemfontein) across three provinces (North West province, Mpumalanga, the Free State). Calculations were performed to ascertain the number of extreme high-heat days (over 35 °C), as well as rainfall onset and cessation.

Thanks to detailed data collection from various government departments and agencies (the Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development, the Crop Estimates Committee, the ARC, the South African Grain Information Services), we accessed total maize yield per hectare for each study site at the districts level. This data were rigorously interrogated with various statistical tests, including the Mann-Kendall trend test, to identify trends or shifts in weather across the six districts.

Study 2: The second study was limited to two sites, Lichtenburg (North West) and Bloemfontein (Free State), for a more detailed and in-depth analysis across two very different agroecological zones. Sixteen different combinations were simulated using a standard medium-maturing maize variety and a short-maturing variety, two different climate change scenarios (RCP 4,5 and RCP 8,5), and four different planting dates: early (15 November), optimal (15 December), late (15 January), very late (15 February). Where February acts as a negative control and has an expected and consistent outcome regardless of scenario for comparisons (an unexpected result for a February planting would indicate issues with the modelling).

The growth and development of the crop were assessed at two stages: vegetative growth phase (VGP) and reproductive growth stage (RGP). The heat unit (HU) requirements, days to flowering, and days to maturity for a standard short- and medium-maturing maize variety were used. The reason for including a short-maturing variety was to test whether this cultivar would be a possible alternative if the rainy season was shortened due to delayed rains. Climate change models were downscaled to the two selected districts in South Africa and climate conditions were simulated from the year 1961 to 2099. Projected maximum and minimum temperatures, number of high-heat days, and rainfall among other parameters were assessed for each time point and location.

Study outcomes

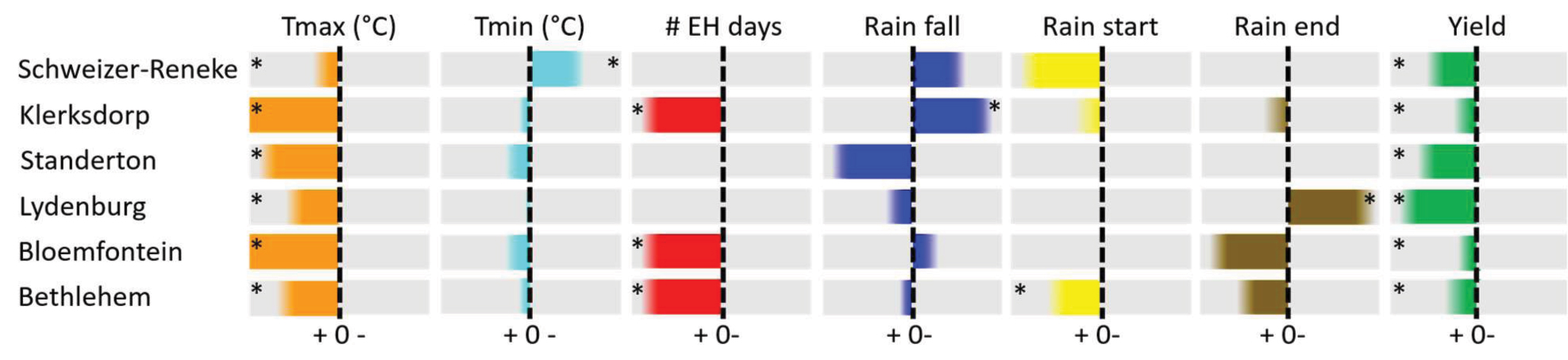

Study 1: The trend analysis supports current climate change data, which suggest a general warming. Over the last 30 years all study sites showed significant increasing trends in the maximum temperatures. Three of the six sites (Klerksdorp, Bloemfontein, and Bethlehem) have significant increasing trends in the number of days above 35 °C, suggesting that heat waves have become more common in these regions. In all the locations studied, yields showed a positive trend, indicating that despite these changes in weather variables all locations continued to show an increase in yield over the same time period. This suggests that currently our agricultural practices and cultivars are maintaining and improving yields even as weather patterns shift, likely due to our producers’ experience with high seasonal variability.

It is important to highlight that during the time frame assessed in this study, maize GMOs (genetically modified organisms) and significant mechanisation were introduced to the country, showing the importance of embracing new technologies to maintain and improve yields as climate change progresses. There were some interesting comparisons to be made across the study where Schweizer-Reneke, Standerton, and Lydenburg had the strongest positive trends for yield and very few significant trends for weather variables. Klerksdorp, Bloemfontein, and Bethlehem appear to have small positive yield trends, and it is interesting that these three locations had strong trends for increasing temperature and number of high-heat days. Bethlehem in addition had a significant trend for delayed rains and Klerksdorp showed a significant trend for lower rainfall, suggesting these limited the increases in yield of the time period studied.

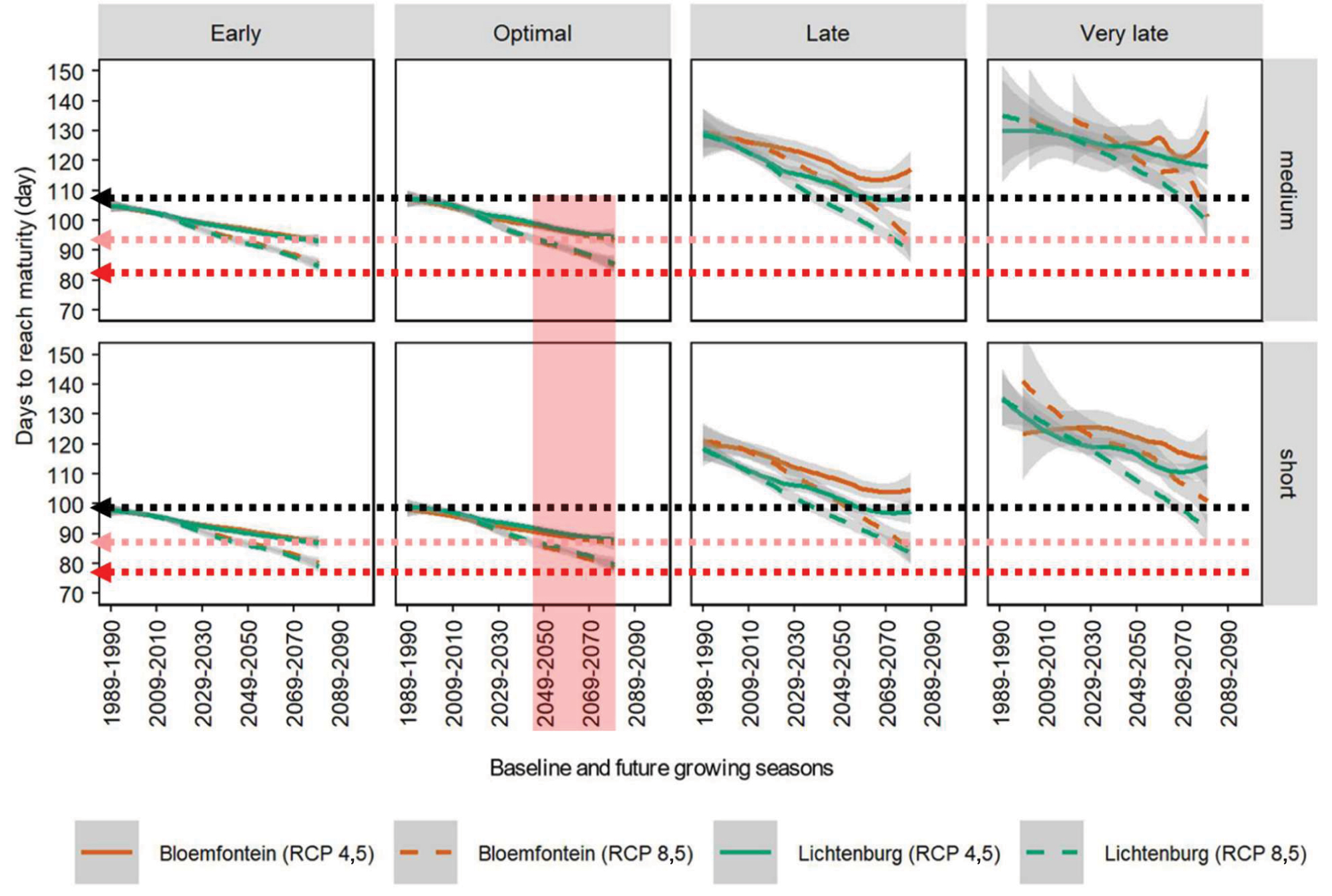

Study 2: Based on the weather shifts observed in Study 1, the changes can be extrapolated into the future based on current climate change models (RCP 4,5 and RCP 8,5). These new climates are then assessed against maize growth based on what we know about the conditions required for good crop production and how deviations in these conditions will impact maize development. One of the big changes we observed was that at the optimal (15 December) planting date the number of days to maturity will decrease by about ten days for both the short and medium varieties by 2070 for RCP 4,5 and up to 20 days for RCP 8,5 (Figure 2 red and pink arrows).

Decreases in days to maturity are known to impact biomass accumulation and will likely result in lower yields. These projections are based on current climate models and current cultivar selections and do not account for development of climate-smart or climate-resilient varieties. But these findings highlight that it is critical to start developing and breeding for climate resilience so that climate-smart cultivars will be available by the time these changes begin to significantly impact yields. We also noted that at the late planting date (15 January) both varieties seemed to reach the standard 100/110 days to maturity at RCP 4,5. This suggests that under moderate climate change scenarios, shifts in planting dates might help maintain yields, but that the planting window needs to be carefully monitored in semi-regular trials over the next 20 to 30 years before recommendations can be made.

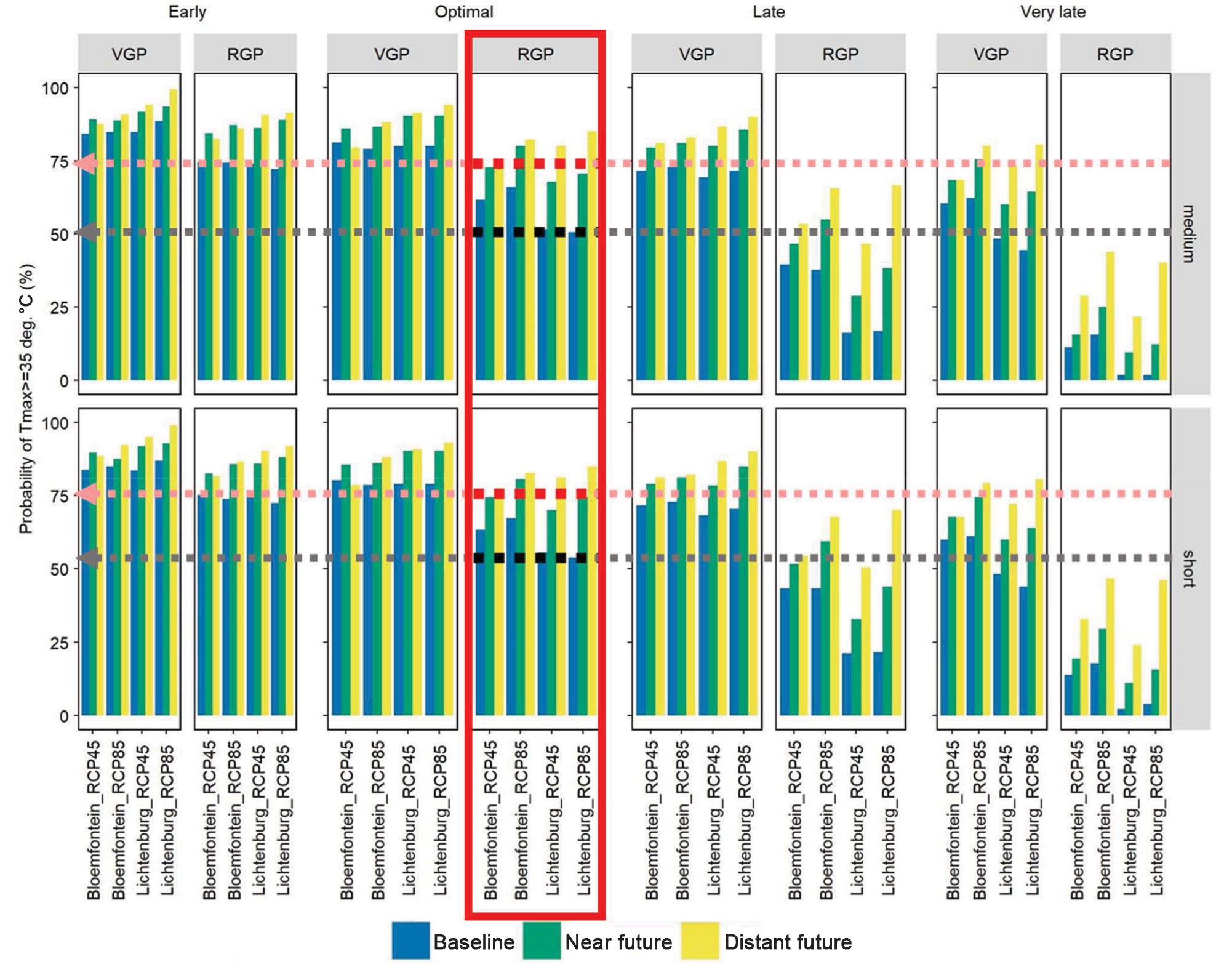

An assessment of how the number of days above 35 °C will change as climate change progresses in the future indicated a steady increase over time. This means more heat waves are likely in Bloemfontein and Lichtenburg in the future (Figure 3). We investigated when in a crop’s development would these ‘potential heat wave days’ be more likely and found that for the optimal planting date in the near and distant future (2050 to 2100) the reproductive growth phase (RGP) of both short- and medium-maturing varieties would be more exposed to high-heat days. This is a concerning finding since maize flowering and pollination are known to be negatively affected by high temperatures and it suggests that in the future the current optimal planting date may limit yields due to heat stress during silking and tasselling. The late January planting date had fewer exposures to high-heat days in the future. This again suggests planting dates must be monitored to ensure crop development is aligned with the best climate as we move into the future.

Concluding remarks

Despite the debate on cause or extent, there is little doubt that climates are changing globally and impacting crop production. In South Africa we observed that climates are shifting at the district level and these shifts are different between districts. We observed that already all our locations have increased in temperature or the number of high-heat days. We also observed that Klerksdorp has decreasing rainfall, while Bethlehem has a later start to the rainy season and these correlated with smaller yield gains (Figure 1).

Using these baseline temperatures, we could extrapolate to how climate may look in the future and what this might mean for planting date. We projected that in the near to far future (2050 to 2100) the optimal planting date will result in shorter times to maturation, which could limit yields (Figure 2) and we observed that during the optimal planting dates crops in the silking and tasselling stage may be exposed to more heat waves, also threatening future crop production. There is some small evidence that the later planting date might have more favourable time to maturity and fewer high-heat days, but water availability could not be accurately predicted and could limit alternate planting dates.

This study highlights the need to semi-regularly monitor planting dates as climate change progresses so that we can be sure our planting dates are still relevant. A long-term planting date study coordinated by Grain SA in the Climate Resilience Consortium shows that currently the optimal planting dates remain that same with the best yield resulting from mid-December plantings in these regions (https://sagrainmag.co.za/2022/11/04/when-is-it-too-late-to-plant/).

Links to freely available full research papers:

References

- Archer, E, Landman, W, Malherbe, J, Tadross, M & Pretorius, S. 2019. South Africa’s winter rainfall region drought: A region in transition? Climate Risk Management, 25, p.100188.

- Wójtowicz, M. & Wójtowicz, A. 2023. Significance of direct and indirect impacts of temperature increase driven by climate change on threat to oilseed rape posed by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Pathogens, 12(11), p.1279.

- Mangani, R, Mazarura, J, Matlou, S, Marquart, A, Archer, E & Creux, N. 2025. The impact of past and current district-level climatic shifts on maize production and the implications for South African producers. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 156(2), p.109.

- Mangani, R, Gunn, KM & Creux, NM. 2023. Projecting the effect of climate change on planting date and cultivar choice for South African dryland maize production. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 341, p.109695.