In modern maize production, staying green isn’t just a visual cue – it’s a measurable advantage and sign of a healthy, powerful crop. Understanding how genetics, physiology, and crop management interact to preserve staygreen is key to unlocking consistent, high-performing maize across diverse environments. Dr Rikus Kloppers, crop disease specialist heading up Robigalia CropCare, delves into the topic.

In modern maize production, staying green isn’t just a visual cue – it’s a measurable advantage and sign of a healthy, powerful crop. Understanding how genetics, physiology, and crop management interact to preserve staygreen is key to unlocking consistent, high-performing maize across diverse environments. Dr Rikus Kloppers, crop disease specialist heading up Robigalia CropCare, delves into the topic.

Benefits that matter

So, what is staygreen exactly? Staygreen is often referred to as the ability of the maize plant to remain green for some time after pollination or, scientifically stated, as delayed senescence of leaves and stalks during the grain-filling period, allowing plants to retain photosynthetically active leaf area during the grain-filling stage.

Staygreen can be the result of either an inherent genetic characteristic, a morphological trait of the specific genetic background plant, or secondly, a physiological indicator of stress tolerance, often linked to yield stability under drought, heat, and disease pressure.

The result? Staygreen offers two significant benefits:

- Yield stability: Extended photosynthesis during late reproductive stages supports grain filling and leads to higher kernel weight and test weight. By maintaining assimilate production throughout the effective grain-filling window, staygreen hybrids sustain yield even under stress. Studies have shown yield increases of 15 to 25% under drought conditions; while under nitrogen stress, these hybrids managed to maintain green leaf area for at least ten days longer, resulting in up to 1,5 t/ha yield advantage.

- Stalk integrity: Delayed senescence strengthens stalks and reduces lodging risk by limiting the remobilisation of nutrients from stems, preserving plant architecture and tissue integrity. This improved stalk strength lowers the incidence of late-season lodging, enhancing harvest efficiency and grain quality. Studies show that stronger stalks can reduce lodging by 20 to 40%.

A promise of performance

Staygreen is associated with delayed onset of senescence and prolonged, sustained activity of photosynthetic machinery beyond the flowering stage – unlocking a wealth of agronomic advantages. In essence, staygreen serves as a proxy to understand how a hybrid manages the source-sink relationship during late reproductive stages. Source-sink is when kernels draw carbon from vegetative tissue (stem and leaf reserves) to support grain filling.

During the critical grain fill period (14 to 21 days after pollination) the average kernel can add up to 3 mg/kernel/day. In hybrids which have an effective source-sink mechanism, this also means that there is a decrease in stem starch content in the R3 to R5 stages of approximately 26 to 34% and a higher 1000-kernel weight of 19 to 25%. Kernel sink strength is a decisive factor in determining final grain weight and efficiency of carbon use during grain filling.

Yield is not fully determined once maize dents. Kernel moisture at the beginning of R5 is about 60%, and dry matter is only 45% of final total dry matter with black layer still over 30 days away. Therefore, final yield can be affected, plus or minus, by 30%.

It is, however, important to remember that it is not just genetics when it comes to healthy maize production – crop management contributes heavily to healthy yields in the long run. By preserving green leaf area after flowering and staving off premature senescence, we give the plant the power to meet kernel demand, maximise carbon flow, and deliver kernels that reach their full potential. Staygreen, in this sense, is more than a trait – it’s promise of performance.

How can one obtain staygreen in maize?

Staygreen in maize hybrids is not a single magic trick – it emerges from two complementary approaches: smart genetic selection and effective crop management.

1. Genetic selection:

This is where breeders in breeding programmes select hybrids with natural staygreen traits, which is done through measuring leaf senescence scores post anthesis. Seed suppliers can guide farmers towards hybrids with proven staygreen potential.

Not all staygreen hybrids are created equal, though, and there are substantial differences between longer- versus shorter-season hybrids. Longer-season (late-maturing) hybrids generally maintain an extended leaf area duration because they have a longer grain-filling period. Staygreen is often more visually pronounced in these hybrids because the plant’s natural senescence is spread over more days. These hybrids can accumulate more dry matter, but they typically reach black layer later, meaning higher kernel moisture at harvest. Long-season hybrids reach black layer later (65 to70 days after pollination). Strong staygreen in these long-season hybrids can delay dry-down.

Shorter-season (early-maturing) hybrids, on the other hand, show a faster onset of natural senescence because their grain-filling window is shorter. These hybrids reach black layer earlier (50 to 55 days after pollination). Even in this case staygreen remains beneficial, but the visual difference is subtler than in the long-season counterparts (since leaf area duration is naturally shorter). They usually dry down faster, so even with staygreen, kernel moisture is lower at harvest. Staygreen in short-season hybrids helps buffer stress, but they seldom hold greenness as long as late-maturity types.

Regional conditions also shape the ideal staygreen strategy. To this extent, you will see long-season staygreen hybrids thrive in regions with high disease risk and cool, wet climates – but there would be a need for either drying facilities or a late harvest. In dryland/stress-prone areas short-season staygreen hybrids are valuable because they balance yield stability with acceptable harvest moistures.

Disease management also plays a critical role: Longer-season hybrids generally face prolonged disease exposure (which is mitigated by strong staygreen characteristics), making fungicide application more critical in late stages. On the other hand, short season hybrids in South Africa are normally from corn-belt genetics and not as tolerant to diseases as the typical African germplasm. In these quicker hybrids a more comprehensive full-season fungicide spray programme is required.

2. Stress management

Even without a strong genetic staygreen trait, farmers can nurture it through management. This approach manages plant stress through optimal fertilisation, proper plant density to reduce early senescence, and effective disease control, helping maintain photosynthesis during reproductive stages.

So, what about diseases and fungicides?

The connection between foliar disease, stalk strength, and lodging isn’t always straightforward – but one truth stands out: healthy, disease-free leaves drive sustained photosynthesis, stronger stalks, and heavier kernels. When leaves stay green and functional for a longer period, yield potential climbs.

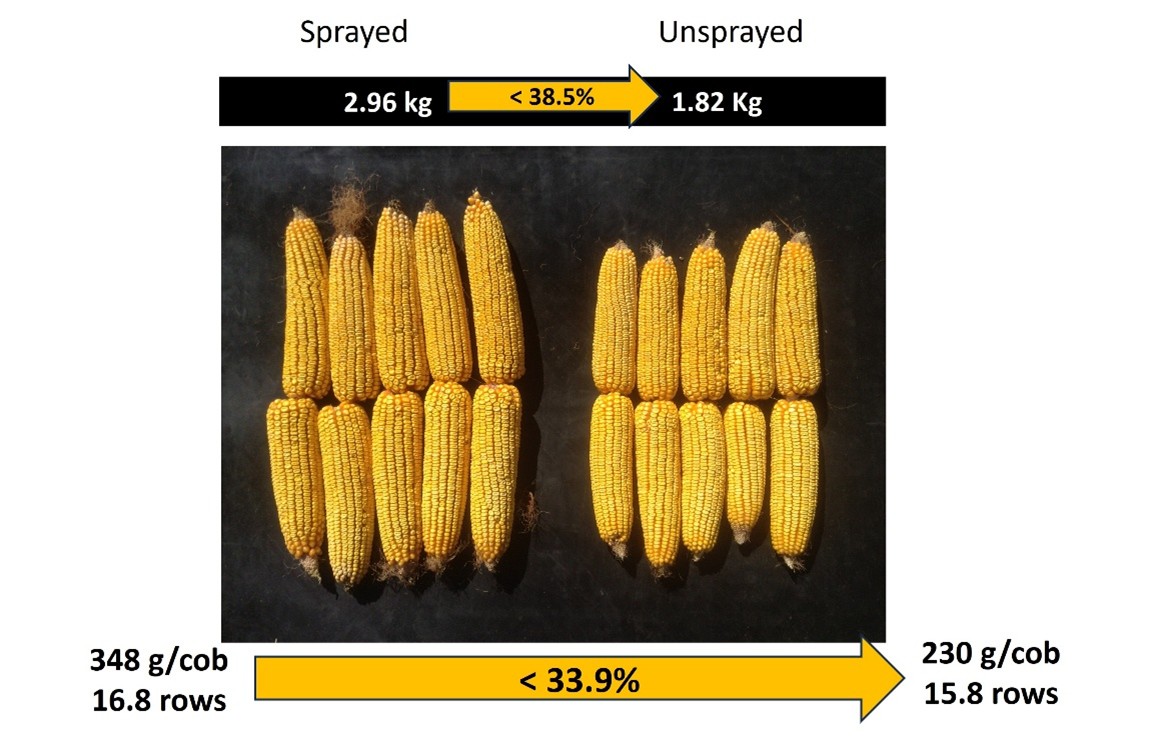

Foliar diseases in South Africa can reduce yields by 30% or more, depending on the pathogen, disease severity, environmental conditions, and hybrid tolerance – all key factors in the so-called disease triangle. The main fungal disease culprits impacting local maize production are grey leaf spot (Cercospora zeina), northern corn leaf blight (Setosphaeria turcica), and common/brown rust (Puccinia sorghi). In regions with high disease pressure, these diseases come in early and effective disease control is based on early preventative and follow-up spraying.

Late-season fungicide applications, on the other hand, only pay off when disease pressure and conditions justify the investment. In drier, low-disease regions, fungicides often provide little economic return. Across the ocean, US growers face different enemies, namely southern rust (Puccinia polysora) and tar spot (Phyllachora maydis). Both strike late in the season, and farmers have to spray at least once and sometimes more in the reproductive stages of the plant.

These diseases spread quickly and speed up leaf aging by damaging green tissue. This directly reduces staygreen capacity, shortens functional leaf area duration, and reduces photosynthesis during grain fill. While southern rust has already made appearances in South Africa, its impact has been relatively mild compared to other markets. Tar spot has not been reported in the region.

An interesting observation around these late-season fungicide applications relates to how they reduce the stress on the plant, prevent premature senescence, and give the staygreen required extended kernel fill. By extending grain fill through management by three to five days, increased kernel weight is around 10% and yields are increased by anything between 0,6 to 1,3 t/ha.

Modern fungicide programmes rely on mixing and rotating active ingredients to balance preventive and curative action while avoiding resistance buildup. The main fungicides used in maize are triazoles (DMI 3), strobilurins (QoI 11), SDHIs (7), or their combinations. Among them, strobilurins are renowned for their general plant health and staygreen effect. By inhibiting ethylene production, the plant stays greener longer and relieves stress.

Additionally, it lowers the stress effect on the plant by allowing the plant to lower its respiration rate when temperatures are high, optimising water usage – particularly valuable in dense canopies and hot conditions. All these stress factors can result in premature senescence in plants, which may be managed through the application of fungicides – which offer disease control, but also maintain overall plant health and reducing stress.

Ultimately, fungicides are only one piece of the staygreen puzzle. True plant health – and the ability to preserve the staygreen effect – come from an integrated disease management strategy that incorporates fungicides, the use of resistant high yield potential hybrids, and the implementation of appropriate agricultural practices. Together, these create a resilient, high-performing maize crop that stays greener, stronger and more productive for longer.

In closing

In the end, staygreen is far more than a visual trait or plant characteristic – it’s a window into the inner workings of a maize plant. It’s where genetics, environment, and crop management intersect to shape resilience, yield stability, and harvest quality. By choosing the right hybrid, managing stress, and protecting the crop from disease, growers can extend the plant’s productive life and unlock fuller kernel potential.

Staygreen is, ultimately, a measure of balance – between photosynthesis and respiration, between growth and defence, and between nature and nurture. The greener your maize stays, the longer it performs – and the better it pays.