August 2018

DR DIRK STRYDOM, manager: Grain Economy and Marketing, Grain SA

In the last four years Grain SA worked hard in bringing changes to the wheat industry in order to make it more sustainable for local wheat producers. In April, an article was published in SA Graan/Grain explaining the progress as well as the challenges with the current turnaround strategy.

It is no illusion that wheat producers are under tremendous financial pressure and that the sustainability of wheat production is diminishing. The droughts of the past few years fast-tracked and amplified this diminishing sustainability. Several of the producers and industry role-players are under the impression that these changes have not had a substantial impact on the local producers’ financial position.

Various economists, myself included, were under the impression that if the Western Cape region produced below the demand of ± 600 000 tons the problem of an oversupply (regional export status) would be solved or at least be reflected in pricing and premiums offered to producers. During the past season though, the drought facilitated this process and less than 600 000 tons were produced, with very little effect on prices.

Various economists, myself included, were under the impression that if the Western Cape region produced below the demand of ± 600 000 tons the problem of an oversupply (regional export status) would be solved or at least be reflected in pricing and premiums offered to producers. During the past season though, the drought facilitated this process and less than 600 000 tons were produced, with very little effect on prices.

We were wrong, mainly because we underestimated the effect of the imbalance of market power and the impact of imports. This emphasised the importance of the turnaround strategy; therefore Grain SA asked the Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy (BFAP) to investigate the possible impact of the turnaround strategy and the benefits it might hold.

One of the greatest concerns within the wheat industry is that the local producers produce some of the best quality wheat in the world, but they don’t receive prices suitable for this superior quality. The prices received are more suitable for imported Russian wheat (comparative level of protein, but of lower quality) and not that of hard red winter wheat (comparative quantity and more or less the same quality of wheat produced locally).

How do you address this problem? You change the grading regulation to accommodate quantity in accordance with that of imports. This is only quantity in terms of protein content, which can be managed by means of production practices. Millers and bakers are more concerned about quality in terms of intrinsic values; in layman’s terms the quality of the protein.

Secondly you need to increase the wheat yield. Protein quality (intrinsic values) and yield are negatively correlated. Therefore, the higher the quality, the lower the yields. This means that we need to breed new cultivars to increase yield. This, however, is a timeous process.

In the meantime support is needed to keep producers in production and more competitive than imports until there are cultivars available to increase the yield. This is done through the import tariff, which ensures that the local processors prefer local produce.

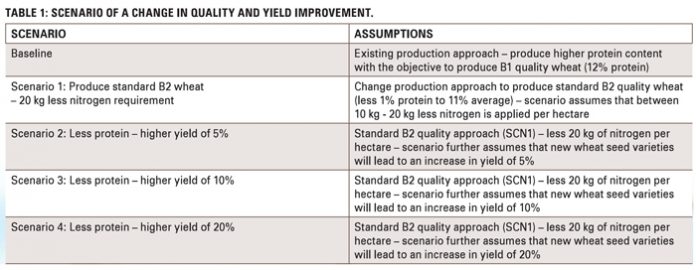

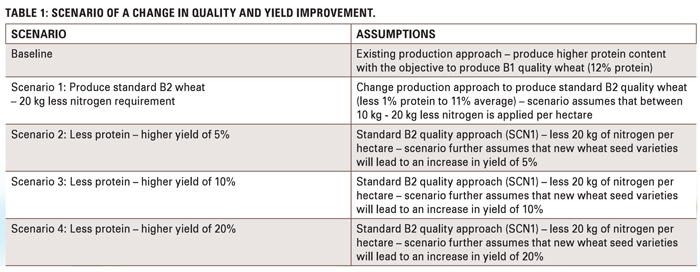

So, what is the impact of all this on the sustainability of the producers? According to BFAP, if the local price moves from a Russian import parity level to a hard red winter parity price, the hectares will increase with ± 10 000 ha, while the price will move from ± R3 800/ton level to ± R4 200/ton.

As elucidated in Graph 1, a substantial increase is required to obtain gross margin levels. Keep in mind that the gross margin constitutes only the income with a deduction of the direct costs. In the Swartland area, R2 400/ha must be utilised to pay fixed costs. If you lease land an additional R2 700/ha has to be deducted and then you still need to buy equipment, pay maintenance, pay labour, electricity, land tax, living expenses etc. This means that the increase in the gross margin will assist the producer to pay fixed costs and improve sustainability.

In winter grain production, profits are extremely sensitive to yields. With a decrease of 30% yield – similar to the drought – it is clear that producers cannot even make money on a gross margin basis. This means that the producer cannot even cover their directly allocable costs. The opposite is also true: If we can increase the yield of the crops, this will substantially assist in terms of profitability and sustainability.

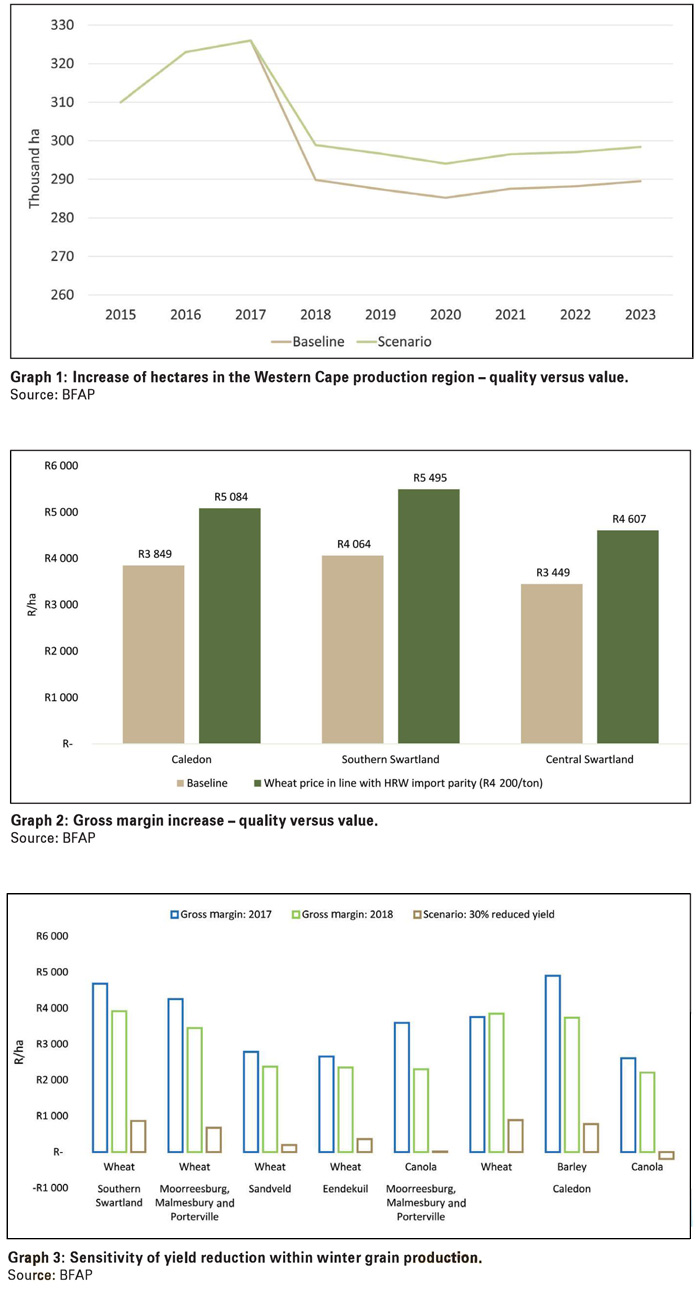

Producers can use less nitrogen in their production systems because of the changes in grades due to lower protein requirement. Keep in mind that, according to the International agri benchmark network, South Africa has the highest production costs. Because of the reduction in intrinsic values to levels that is still competitive with imports it is expected that we can over time increase the yields by 30%. BFAP developed a few scenarios to illustrate this effect.

From this scenario can be deduced that the reduction in nitrogen and the increase in yield can result in an increase in the gross margin; and gross margins can almost double. This means that the producer has close to R6 000/ha to cover fixed costs which makes production more sustainable (Graph 4).

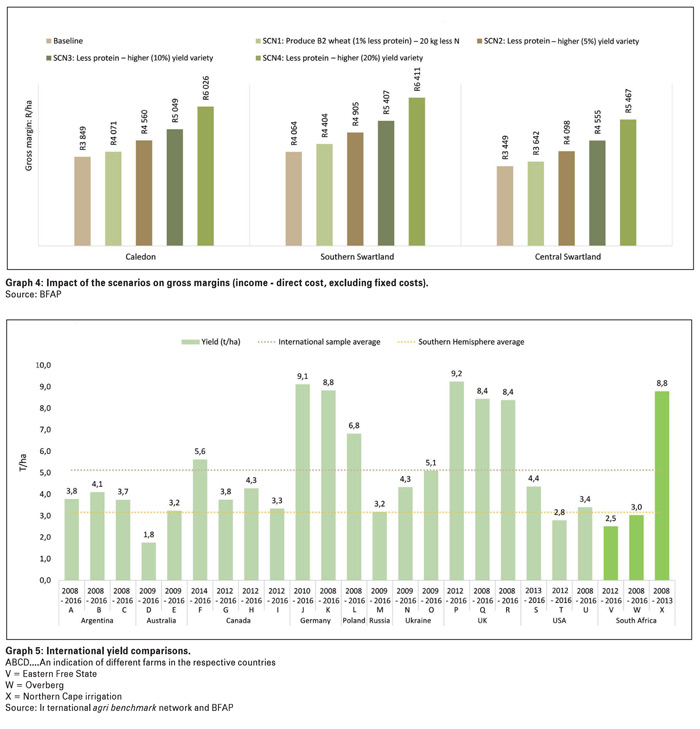

It is also clear from these graphs that the increase in yield has a large impact on the financial position of the producers. The International agri benchmark network also indicated that South African wheat production has a below average yield – even when compared to the rest of the Southern Hemisphere (Graph 5).

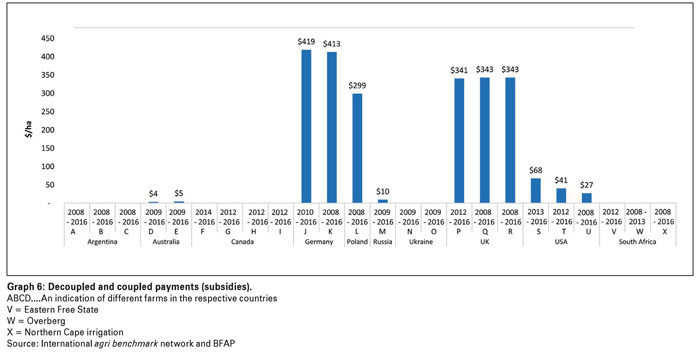

Tariff protection is also very important due to the support that some of the importing countries receive. To put this in perspective, one can compare the decoupled and coupled payments with that of the rest of the world. Germany, which is one of our largest European importers, receives as much as 9/ha. That is almost 80% of the Western Cape producers’ direct costs (Graph 6).

From the above it is clear that an increase in yield – which can be realised by means of new genetics, lowering of quality and a cultivar and technology levy, will substantially assist local producers financially.

Furthermore, the lowering of grading regulations and possible changes in the tariff structures can also assist producers to receive fair value for their crops, based on quality versus price and import competitive levels.

Publication: August 2018

Section: On farm level